23 Things About Capitalism – Things 15 to 17

Today’s post is our sixth look at 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism. We are up to things 15 through 17.

Contents

- Thing 15 – People in poor countries aren’t entrepreneurial

- Thing 15b – People in poor countries are entrepreneurial

- Thing 15c – Conclusions

- Thing 16 – We are not smart enough to leave things to the market

- Thing 16b – limits to rationality

- Thing 16c – Conclusions

- Thing 17 – Education is needed for a country to become rich

- Thing 17b – Education won’t make a country richer

- Thing 17c – Conclusions

Thing 15 – People in poor countries aren’t entrepreneurial

This is a promising headline, but we shall see.

- Conventional thinking is that rich countries are generally more entrepreneurial than poor countries.

I’ll go along with that, to an extent.

- The US and UK are more entrepreneurial than France and Sweden for example.

- But this is to do with labour laws and tax and welfare policies, things that operate at a national level.

Most people would really say that an entrepreneurial spirit – and legislation to match – is what leads to a dynamic economy, which in turn gives a country its best chance of being or becoming rich.

Ha-Joon has cleverly restricted the argument to people rather than countries, and emphasised the wealth gap between rich and poor countries.

I don’t think anyone believes that poor countries are poor because they have no entrepreneurial people.

- Anyone who’s ever been on holiday to a poorer country at least knows that those locals who come into contact with rich foreigners are plenty entrepreneurial.

So there’s a whiff of the straw man about this one.

Thing 15b – People in poor countries are entrepreneurial

Yes, we know that, or at least that some of them are.

Ha-Joon says that the problem for poor countries is the “absence of productive technologies and developed social organizations, especially modern firms”.

He points to the disappointing experience with microcredit as showing the limits of individual entrepreneurship.

Micro-credit – itself credited to Muhammad Yunus, an economics professor who set up Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1983, and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 – can help one-man (often one-woman) bands keep the wolf from the door, but it can’t make a poor country rich.

- In fact, micro-credit needs to be subsidised by the state (to avoid charging very high interest rates to the not very creditworthy poor, which in turn prevents them from making much of a profit).

- It also turns out that most loans are for “consumption smoothing” (paying for a wedding or covering an illness) rather than for real entrepreneurial activities.

- And although a few early entrepreneurs make money, easy credit lowers barriers to entry and profitable markets (eg. the famous “telephone ladies”) become crowded and non-profitable. ((This is the fallacy of composition – because some people can succeed with something, it doesn’t mean that everybody can ))

Because they were unable to move into phone manufacture, or software development (for phone games), the telephone ladies were unable to remain profitable.

Skills and technologies – and infrastructure like company law and an education system – are the limiting factors, not credit.

- A lack of cooperation between similar enterprises in developing countries is also an issue.

By contrast, in rich countries, people mostly work for big firms or for the government, and don’t need to be remotely entrepreneurial to survive.

- I’ll go along with all that, though we might disagree over what to do about it.

Thing 15c – Conclusions

Ha-Joon has hijacked this Thing to an extent, with the focus on developing countries once more.

- I feel we’ve learned more about micro-finance than we have about entrepreneurship.

- At least that is a relatively interesting topic in developmental economics.

I also feel that this was a straw man Thing, with few people really believing that poor countries are poor because they lack entrepreneurs.

Nevertheless, I’ll give Ha-Joon the full point on this one because he is technically correct (which as we all know, is the best kind of correct).

- That takes his score up to 7 and a half out of 15 – he’s back to 50%.

Thing 16 – We are not smart enough to leave things to the market

Free marketeers like myself say leave markets alone.

- Ha-Joon says that we say this because we think that individuals and firms – “as collections of individuals who share the same interests” – are rational.

I think nothing of the sort, but I do think that people know their own interests and circumstances best, and that attempts (by the government) to restrict freedom of action will backfire, as people do something different from what was intended.

Ha-Joon thinks the argument is about the “inferior information” held by government, whereas I see it more as a King Canute kind of argument – you can’t get the sea to go back.

- Neither can you get people to do things that are not in their own interests.

In particular, if you try to get people to do things that don’t benefit them personally, you won’t be getting their best efforts, and in the long-run, the country won’t prosper. ((I’m ignoring the moral argument here and focusing on economics – I also believe that the government works for the people and should be helping them to achieve their goals, rather than the other way around ))

- This promises to be a meatier debate.

Thing 16b – limits to rationality

Ha-Joon’s critique of free markets is based around the limits to rationality.

I have no issue with the concept of irrational behaviour – a lot of investing technique assumes this – but I do object to this being used to justify nanny state regulation to protect us from ourselves.

- Adults in a free country should be able to make mistakes and bear the consequences.

Irrational behaviour will be punished by free markets, and those actors will either correct their behaviour or be wiped out, removing them from the market as economic actors.

- The real role for government is in regulating markets to ensure they operate correctly.

The two key problems are monopolies and oligopolies (which allow firms to charge higher than market prices) and externalities (pollution and climate change, for example).

- Here there is a clear role for government regulation.

- But often, the regulation would be simply designed to repair the market mechanism (eg. by introducing tradable pollution or carbon credits).

Ha-Joon re-tells the tale of Long-Term Capital Management, a failed hedge fund run by the people who won the Nobel Prize in Economics for their options pricing model.

- He seems to think that because prize winners make mistakes in financial markets, we shouldn’t have free capital markets.

I think we need to do better on having “too big to fail” players in financial markets, and we also need to find solutions to crises that don’t involve propping up zombie enterprises.

- Preventing capital markets from allocating capital correctly ((As the current system of financial repression via low interest rates is doing, incidentally )) will do more harm than good.

He also thinks that the Bernie Madoff pyramid scheme is instructive.

- With all due respect to those who lost money, it is instructive only of people’s greed, and willingness to believe what is convenient.

- Anyone familiar with markets who saw the returns from Madoff’s fund would not have invested.

- Anyone not familiar with markets should have been advised by someone who was.

- Note that decades of service within the asset management industry need not qualify you as familiar with markets.

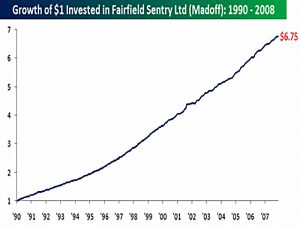

We don’t normally have pictures in this series of articles, but I’m going to make an exception here.

Here is the chart of Madoff’s returns:

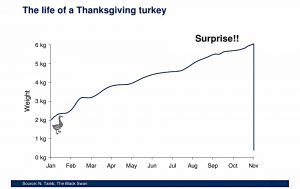

And here is the chart of a turkey’s weight in the run up to Thanksgiving (it would be Xmas over here in the UK), made famous by Nassim Taleb’s book Black Swan:

Spot the similarity?

- This is what they mean when they say past returns are no guide to future returns.

I’m going to cut Ha-Joon some slack in that he was writing soon after the 2008 financial crisis.

- We were all under a lot of stress in 2009 and 2010.

The 2008 crisis was caused, fundamentally, by lending money to people who couldn’t pay it back.

- The stupidity of that is understandable by any reasonably intelligent person.

That this lending was done by over-incentivised salesmen, employed by banks who quickly sold on the debt to investment firms who then sliced and mixed it up to make it seem less risky, doesn’t change this fact.

The lessons from 2008 are:

- don’t lend to people who can’t pay you back

- don’t buy things that you don’t understand

These lessons were well known before 2008, and are not too complex to understand.

Ha-Joon suggests that the human reaction to complexity is to restrict freedom of choice.

- He uses personal routines, queueing for a bus and chess heuristics as examples.

On the personal level, through the creation of habits and routines, I wholeheartedly agree with him.

- My personal weekday routine is highly regulated, from when I sleep, to what I eat, to what I wear, to how and when I exercise.

- But it’s a personal choice, and it wouldn’t work for everyone.

Voluntary restriction is not the same thing as government intervention.

- If I didn’t have the freedom to vary my routine at the weekend, I would probably be unable to stick with it through the week.

The same applies to markets, and in particular to the capital markets that Ha-Joon regards as the most complicated and difficult to understand.

- In the same way that most people play chess adequately via a few rules of thumb, it is possible to navigate the financial markets safely via a few golden rules. ((Take a look at my MoneyDeck series of rules if you aren’t convinced ))

In contrast, Ha-Joon suggests that “financial instruments need to be banned unless we fully understand their workings and their effects on the rest of the financial sector and, moreover, the rest of the economy.”

- He thinks that it’s no different to banning “drugs, cars, electrical products”.

I’m not clear how the mechanisms of drug- or crash-testing would transfer across to financial instruments.

Thing 16c – Conclusions

Ha-Joon comes across as though he is suffering from PTSD on this one.

- He doesn’t seem too familiar with capital markets, but uses them as his core example of why markets need regulation.

The 2008 crash was terrible, and avoidable, but we’re all still here, aren’t we? ((In fact, many of us are considerably more wealthy than before ))

- The analogy with car crashes and plane crashes is false.

Financial booms and busts will always happen, but you don’t need to get caught up in them if you don’t want to.

- Don’t risk money that you can’t afford to lose, and don’t buy anything that you don’t understand.

- Exactly the same advice that I would have given you in 2007.

I’m going to give Ha-Joon zero on this one.

- That puts his score at 7 and a half out of sixteen, or 47%.

Thing 17 – Education is needed for a country to become rich

Another developmental topic, and not one that I’m particularly interested in.

- I am however interested in the over-selling of education as a panacea to all ills (in rich countries) , so maybe we can find some common ground.

The conventional wisdom contrasts the educational achievements of successful Asian economies with the lack of education in poor Sub-Saharan African countries.

- As work transitions from agricultural / mechanical / industrial towards a knowledge economy, this gap will only get wider.

Thing 17b – Education won’t make a country richer

Ha-Joon has four points (and covers a lot of economic history to support them):

- There is little evidence that more education leads to greater national prosperity.

- Much of the knowledge gained in education is not relevant for productivity enhancement.

- The idea of a new “knowledge economy” is problematic, as knowledge has always been the main source of wealth.

- With increasing de-industrialization and more mechanization, knowledge requirements may have fallen for most jobs in the rich countries (there are a lot of entry-level unskilled service jobs these days).

I have no particular disagreement with – nor any particular interest in – any of these statements.

As previously, he argues that what really matters for national prosperity is the nation’s ability to organize individuals into enterprises with high productivity.

- This I do agree with.

My own take on education in society is that it follows an S-curve.

- A certain level of education is needed across the board for a society to be productive.

- Adding more education will not directly increase productivity.

- Preparing people to be productive in the jobs that are available is what matters (work backwards, duh).

- This probably means that we need more apprenticeships and fewer exams.

In addition, many of the most important topics (finance and economics for two) are not taught as part of the core curriculum in the UK.

- And the majority of decision makers in UK society lack what I would call a rounded education (in particular, they mostly know no maths or science).

Tony Blair’s famous “Education, education, education” mantra may have won him elections, but it’s done a lot of damage to society.

- More than 50% of students now go on to “university”, with attendant expectations, despite taking courses that have no economic value whatsoever (literature, history, philosophy and music, not to mention the many “subjects” invented in the last 20 years).

- They rack up average debts of more than £40K, more than half of which will never be repaid.

Switzerland was able for decades (until the mid 1990s) to maintain high productivity with only 10-15% university enrolment, so higher rates than this are not needed.

As Ha-Joon explains, education is a “sorting” mechanism, designed to establish your ranking in the hierarchy of employability.

- The fact that you have graduated tells employers that you “are likely to be smarter, more self- disciplined and better organized than those who have not”.

Sorting is a zero-sum game, and investing more resources into it will not help the economy.

- When more people graduate, the value of being a graduate must fall.

- 45% of UK graduates now have to take “non-graduate” jobs, at non-graduate pay.

Now you need a masters to stand out.

Thing 17c – Conclusions

Ha-Joon and I are interested in different contexts, but we are in agreement about the basic substance: more and more education is not the answer.

- I’m going to give Ha-Joon the whole point again, bringing his score up to 8 and a half out of 17, or 50%.

Today’s three things were decent again – I particularly enjoyed rehashing the case for free markets and the details of the 2008 financial crisis.

- Tellingly, those were the only areas of significant disagreement this week.

We’ll be back in a couple of weeks with another three things – we have six more to go.

Until next time.