Buffett’s Annual Letters – My First Time

Today we’re going to look at Warren Buffet’s 50th Annual Letter to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway.

Contents

- Buffett’s Annual Letters

- Performance record

- Book value vs. intrinsic value

- 2014 performance

- Insurance

- Regulated, Capital-Intensive Businesses

- Manufacturing, Service and Retail

- Financial Products

- Investments

- The plan for the future

- Acquisition criteria

- A few more quotes to finish

- Conclusions for BH

- Conclusions for the Private Investor

Buffett’s Annual Letters

The 42-page letter in question covers 2014, and was released back at the end of February this year – so this is not a topical post.

For at least 10 years, I’ve been meaning to read Buffett’s annual letters. They come highly recommended, and create quite a bit of media frenzy each year across the Atlantic.

But I still haven’t read any of them. So I figured the best way to force myself was to make the exercise into a series of blog posts.

Don’t expect any startling insights – I’m some way out of my comfort zone, and no expert on Warren. But I’ll do my best to pick out what seem like the highlights for UK investors, and hopefully save you some time if you haven’t yet read the letters.

I apologise in advance for the wall of text, but Warren doesn’t seem to be a fan of pictures or diagrams.

I’m starting with the most recent letter, which happens to be the 50th. If this post goes well, I’ll work my way backwards.

Good luck everybody.

Performance record

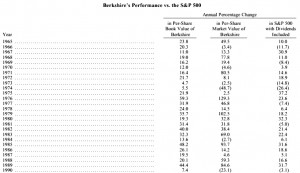

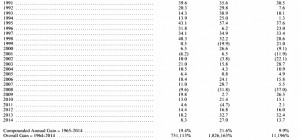

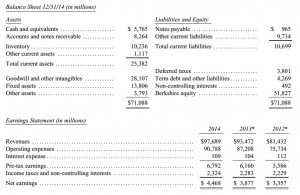

The report begins with a table summarising year to year performance relative of Berkshire Hathaway (BH) to the S&P 500.

- in 2014, book value was up 8.3% and the BH share price was up 27% (against 13.7% for the index)

- compound annual increase in book value over 50 years was 19.4%; the share price compounded at 21.6% (against 9.9% for the index)

- this means that over the 50 years, the book value has increased by 7,511 times, and the share price by 18,261 times (during the same period the index is up 112 times)

- during the same period, the purchasing power of the dollar fell by 87% (as measured by CPI), so $1 in 2014 is equivalent to 13¢ in 1965

It’s probably significant that page 1 is a performance table – who wouldn’t want to stress a track record like that.

Interestingly there’s no mention of valuation measures (eg. P/E ratio – 17.3 when I looked this morning) for BH.

Book value vs. intrinsic value

Apparently the share-price column is a new addition. Historically the comparison was simply between the S&P 500 and the book value, which was taken as a crude measure of the intrinsic business value.

- in the early years, BH mainly held listed securities that were “marked to market” – this meant that book value and intrinsic value were closely related

- now BH owns and operates large businesses, which are worth much more than book value

- since book value is never revised upwards to reflect this, the gap between book and intrinsic value has increased

- Warren doesn’t rate share prices as a measure in the short-term, but eventually the share price and intrinsic value should converge

- he does believe this has happened in BH’s case – the 18,261 times gain in the share price is roughly equal to the increase in intrinsic value

2014 performance

The initial review of the company’s 2014 performance assumes some familiarity with the conglomerate. Subsidiaries are referred to by acronyms, often with no mention of even what business they are in. This was a surprise to me – the novice reader is thrown in at the deep end. ((Perhaps I should have started at the beginning, rather that working back from the end))

A few highlights:

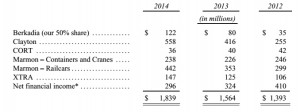

- the “powerhouse five” – the biggest non-insurance subsidiaries, mostly “recent” acquisitions – had record earnings, up $12bn over ten years with only minor dilution in BH shares issued

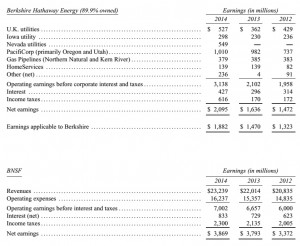

- $6 bn (!) will be invested in BNSF (a railroad) to improve its performance

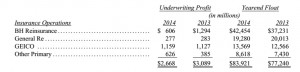

- the insurance business made a profit and provided a “float” – money from upfront premiums that can be invested on BH’s behalf – of $84 bn

- the insurance business made an underwriting profit for the 12th successive year

- the acquisition of Heinz in partnership with Brazilian group 3G Capital is going well and Warren expects to partner with 3G in more deals

- BH now has 340,499 employees, of whom only 25 work at the HQ

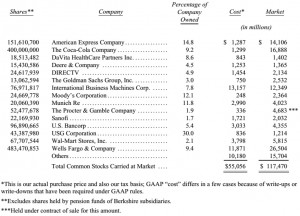

- BH increased its holdings in American Express, Coca-Cola, IBM and Wells Fargo – the “Big Four” non-subsidiary investments

Berkshire now owns 9 ½ companies that would be listed on the Fortune 500 were they independent (Heinz is the ½). That leaves 490 ½ fish in the sea. Our lines are out.

Warren then moved on to review the four key areas of business for BH.

Insurance

- the BH float is likely to decline from 2014’s record $84bn, at up to 3% per year

- the industry as a whole competes away underwriting profits – any aggregate loss is the price the industry pays for the access to the float

- low interest rates reduce earnings on the float and hence profitability

- the economic value of the BH insurance goodwill (from acquisitions) – the price Warren would pay for a float of similar quality – far exceeds the accounting book value

- BH is much more conservative in avoiding risk than most other large insurers, and will walk away if the required premium for underwriting a risk can be achieved

- GEICO is the low-cost operator in US auto insurance and this enables it to grow market share (this is GEICO’s moat)

- GEICO’s gecko spokesman is much better than a human equivalent (no ego, no agent)

Regulated, Capital-Intensive Businesses

These are BNSF (the railroad) and BHE (the energy company). They invest heavily in long-life, regulated assets and have large amounts of long-term debt.

- This debt is not guaranteed by BH

- BNSF has interest cover of 8:1

- BHE’s regulatory risk is lowered by diverse earnings supervised by multiple regulators

- BNSF is the main freight pipeline in the US, carrying 15% of all inter-city goods using a quarter of the fuel per ton-mile as trucks

- BHE is investing heavily in renewables, with $15 bn committed

Manufacturing, Service and Retail

- The figures Warren presents are non-GAAP. ((That is, they don’t follow the US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles))

- Warren thinks his figures better reflect economic reality

- He accepts that intangibles like software deplete, but not customer relationships

- GAAP would require $1.15 bn of amortization charges, of which Warren would call about 20% real

- Non-real charges have risen as BH has grown through acquisition, and will continue to rise

- There is $7.4 bn of intangibles left to amortize, of which $4.1 bn will be charged over the next five years

- When all the intangibles are amortized reported earnings will rise even if real earnings are flat

- For this reason, Warren doesn’t use EBITDA as a valuation guide

- Some of these operations earn from 25% to 100% pa on net tangible assets, after tax

- Others earn well at 12% to 20%

- A few earn badly – Warren’s mistakes – but are usually small

- Overall returns were 18.7% after tax on $24 bn of net tangible assets

- Prices paid for businesses are generally at substantial premiums to net tangible assets (hence the large goodwill figures) so these returns are no guarantee of success

Financial Products

This area includes leasing and rental operations at Marmon (rail cars, containers and cranes), CORT (furniture) and XTRA (semi-trailers, as well as Clayton Homes, the US’s largest home builder with 45% market share and $13 bn of mortgages.

- BH makes its own railroad cars (“tanks”) and sells them on to the leasing division at cost price, which means the book value of the rail fleet underestimates its true value

- Clayton was able to keep building and lending through the 2008 crisis because of BH backing

Investments

The major sale in 2014 was Tesco. Bought for $2.3bn before 2012, Warren started to sell in 2013, selling around 25% of the holding for $43M profit. In 2014 the company lost market share, its margin shrank and accounting problems emerged. The loss for BH was $444M, or 0.2% of total net worth.

Warren points out that BH has only ever sold three investments for a loss of more than 1% of total net worth. All three were in 1974-1975, when they sold things that were to cheap to buy others they thought were even cheaper.

The plan for the future

Warren’s high-level strategy is to increase BH’s per-share intrinsic value through six approaches:

- improving the earning power of subsidiaries

- bolt-on acquisitions to existing subsidiaries

- growth in the non-subsidiary investments

- purchasing BH shares whenever they are at a meaningful discount to intrinsic value

- rarely, if ever, issuing BH shares – “trading shares in a wonderful business [BH] for ownership of a so-so business irreparably destroys value”

- making the occasional large acquisition

Acquisition criteria

The report lists six conditions for BH to be interested in buying a firm:

- Large purchases (at least $75 M of pre-tax earnings unless the business will fit into one of our existing units)

- $5bn to $20bn is the preferred purchase price

- Demonstrated consistent earning power (no future projections or “turnaround” situations)

- Good returns on equity while employing little or no debt

- Management in place

- Simple businesses (BH ” don’t understand technology”)

- A sale price – no unfriendly takeovers, and no auctions

A few more quotes to finish

There are certain things that cannot be adequately explained to a virgin either by words or pictures.

Charlie and I have always considered a “bet” on ever-rising U.S. prosperity to be very close to a sure thing.

You see a cockroach in your kitchen; as the days go by, you meet his relatives.

The … inescapable conclusion to be drawn from the past 50 years is that it has been far safer to invest in a diversified collection of American businesses than to invest in securities … whose values have been tied to American currency. That was also true in the preceding half-century, a period including the Great Depression and two world wars. … It is almost certain to be repeated during the next century.

Stock prices will always be far more volatile than cash-equivalent holdings. Over the long term, however, currency-denominated instruments are riskier investments … That lesson has not customarily been taught in business schools, where volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk.

Borrowed money has no place in the investor’s tool kit.

Market forecasters will fill your ear but will never fill your wallet.

You can’t get rich trading a hundred-dollar bill for eight tens.

If horses had controlled investment decisions, there would have been no auto industry.

Conclusions for BH

- Compound annual growth in the share price of 21.6% over 50 years (vs. 9.9% for the index) is truly exceptional

- Book value is no longer a useful measure for BH

- The float from the insurance business appears to be a key factor in the way BH operates

- Warren thinks the capital-intensive, regulated businesses are undervalued

- Warren doesn’t like the treatment of intangible amortization in GAAP, and therefore doesn’t like EBITDA as a valuation measure

- Warren sees 12% pa return on net tangible assets as a minimum “good” return, and prefers 25%+ pa

- Integration and cooperation between subsidiaries (financial backing, manufacturing items for lease) improves their performance

- The conglomerate structure of BH allows it to allocate capital rationally and at minimal cost – Warren and Charlie are not tied to the history of particular industries, or pressured by long-time colleagues with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo

- The track record and culture of BH means it is now the home of choice for the owners and managers of many outstanding businesses that come up for sale

- The BH plan for the future involves seeking out growth in all possible directions:

- organic growth

- bolt-on and larger standalone acquisitions

- growth in non-subsidiary investments

- controlling or even reducing the number of BH shares in circulation

- BH is now so big that future growth will be much closer to the rest of the market

- At some point in the future, it may not be possible to profitably re-invest all earnings – dividends or buy-back will be needed

Conclusions for the Private Investor

- This is a marathon not a sprint: at this point I’m not convinced that I have that much to show for wading through 42 pages of small print, but I still expect to learn a lot from working my way through all 50 letters

- Warren remains very quotable even after fifty years of his folksy schtick

- Over a multi-decade time horizon, stocks are safer than bonds and cash, even though they are more volatile

- Volatility is not risk

- Always diversify

- Keep costs low

- Target 12-25% return on net tangible assets

- Don’t use leverage

- Don’t try to time the market

- Don’t use EBITDA as a valuation measure

- When problems appear with an investment, sell quickly before things get worse

Until next time.

This post is one of a series on the Warren Buffet Annual Letters. To read the other summaries, go to the Warren Buffet Quotes and Annual Letters page.

1 Response

[…] previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011 and 2010. Today we’ll examine the 2009 […]