Ed Easterling – Risk is not a Knob

Today’s post is a profile of Guru investor Ed Easterling, who appears in John Mauldin’s book Just One Thing. His chapter is called Risk is not a Knob.

This article is part of our ‘Guru’ series – investor profiles of those who have succeeded in the markets, with takeaways for the private investor in the UK.

You can find the rest of the series here.

Contents

Ed Easterling

Ed Easterling runs Crestmont Holdings, a Dallas-based firm that regularly publishes interesting research.

- He also teaches a course on hedge funds at the Cox School of Business at Southern Methodist University.

- He also wrote a couple of books: Unexpected Returns, and Probable Outcomes. (( There are links to these books on the page about Ed’s Half and Half strategy, of which more in a moment ))

We came across Ed back in August 2015, when we wrote about his strategy for playing market cycles, which he calls Half and Half.

- Ed also appears in John Mauldin’s book Just One Thing.

- His chapter is called Risk is Not a Knob.

Risk is not a Knob

The first step toward making money is not losing it.

For Ed, all investments come with risk, and that risk needs to be “respected, assessed, managed, and prudently controlled”.

Where he differs from the typical investment advisor is in his interpretation of the axiom that “if you want greater returns, you have to take more risk.”

- Risk does not create returns.

- Instead, it “drives investors to demand compensation and protection”.

Higher returns are normally associated with higher risks, but not because risk drives returns.

- As Ed puts it:

Risk is not the fertilizer in your garden, it’s the weeds.

What we are after – particularly when markets are at high valuations – is higher returns coupled with lower risks.

Ed is a big believer in the traditional warning:

- Past performance is not an indication of future results.

- Similarly, past risk does not necessarily indicate future risk.

He warns against believing that since volatility is linked to returns, so “interim” losses will inevitably yield future gains.

- But as Buffett often points out – volatility is not risk.

What is risk?

Risk is “the possibility of permanent losses”.

- It has to be a possibility – to be uncertain – because otherwise it would already be a loss, rather than a risk.

- And it has to be potentially negative, because “uncertainty about the size of your gain is hardly risk”.

So we can measure risk in terms of probability and magnitude.

- An investment could have a 20% chance of a 50% loss.

If you combined these two numbers to give a potential downside of 10%, then you would want a potential upside of significantly more than 10% to be interested in the investment. (( Interestingly, this is the way that short-term traders usually assess risk ))

In turn, the returns we require to take on a risk drive the price that we are prepared to pay for it.

- But as we buy, someone else sells, and we can’t both be right about our assessment of the risks and returns.

Modern portfolio theory

Modern portfolio theory (MPT) says that “stocks are riskier than bonds since they have a greater potential for loss”.

- This means that stocks will be priced to deliver higher returns, and you will need a large exposure to stocks to generate higher returns.

- Most investors will choose some mix of stocks and bonds to deliver the return and risk they prefer.

But what happens when stocks are expensive, and priced to deliver low (or even negative) future returns?

- A high allocation to stocks – turning the risk knob – won’t then increase returns, but only risk.

Basically, Ed is saying that the volatility of stocks means that they don’t always have the highest returns (which is obvious when you put it that way).

- The question is what to do about it.

Diversification

On a single investment – assessed as having a 90% probability of a 15% gain, and a 10% probability of a total loss – the outcome will be either a 15% gain, or a total loss. (( The numbers are not particularly representative, but the process for assessing outcomes is ))

- So the expected return is 90% * 15% = 13.5%, minus 10% * -100% = -10%.

- That’s 13.5% – 10% = 3.5%.

The pre-risk return on a single investment is the maximum 15%, and the post-risk return is either 15% or -100%.

- Over 100 such investments, the post-risk return should work out at the expected return of 3.5%

So Ed’s framework for looking at risk only underlines the importance of a diversified portfolio.

Stock market analysis

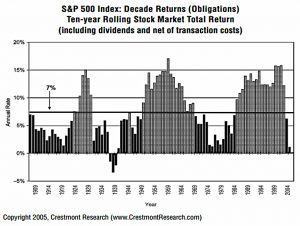

Ed next looks at historical stock return’s using the S&P 500 index.

- Rather than the typical “low bar” of break-even returns for stocks, Ed compares ten-year returns from 1900 with a target net return of 7% pa.

- This net return includes commissions, spreads, management fees, execution slippage, and other transaction costs of 2% pa.

Over the ninety-five decade-long periods since 1900, only forty-five (47%) have achieved 7% pa.

- Further, 37 of these periods (82%) saw increasing PE multiples during the decade.

Volatility

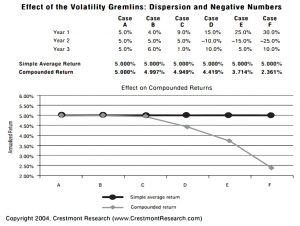

Many market analysts use the standard deviations of returns as a proxy for risk.

- This is a measure of volatility that looks at the spread of returns around their central mean.

A higher standard deviation will lead to a lower compounded return over multiple periods (for the same average return).

- From 1900 to 2004, the average annual US market return was 7.3%, but the compound return over the same 105 years was only 5%.

There is also a psychological aspect to consider – high volatility can persuade investors to reduce or abandon their stock holdings.

There is also the potential for volatility to the downside to lead to cashflow problems and forced sales.

- This should really be dealt with through asset allocation, by holding cash and / or assets that are negatively correlated to stocks.

It is the translation from average returns to compound returns – via what Ed calls “volatility gremlins” – that best illustrates the benefits to the investor of reducing volatility

- and hence closing the gap between average and compound returns.

Portfolio Management

MPT states that “diversification can eliminate the risks that do not provide returns while retaining the risks that do provide returns.”

On this model (the capital asset pricing model, or CAPM), every asset has two risks:

- market risk (beta, or systematic risk) that can’t be diversified away

- unsystematic risk, specific to the asset (the company, in the case of a stock) which can be mitigated through diversification

The theory states that returns come from being in the market – from the systemic market risk.

- MPT portfolios are usually made from stocks and bonds because that’s what was around back in the 1950s, when the theory was developed.

Another way of looking at this is that a diversified portfolio should provide the market return at the lowest possible risk.

Stock market returns are driven by earnings, growth, and valuation (PE rating) changes.

- For high stock returns, you generally need expanding multiples (rising PEs).

For bonds, the key driver is interest rates.

At this point, Ed asserts (without providing direct evidence) that stock and bond markets will – over time – move in the same direction, producing the same risk to the investor.

- From the 1980s to the 2000s, both trends were supportive.

But now PEs are high and interest rates low. (( Interestingly, both have moved to more extreme positions since Ed wrote his chapter ))

- Nowadays, the trends may have reversed to move against investors.

Ed appears to be arguing for the inclusion of more types of assets in portfolios, to diversify away the (presently) similar risks from stocks and bonds.

- But he doesn’t tell us which assets, or how to weight them.

Instead he focuses on our assumptions, counselling us to look to the future when assessing risks and returns, rather than to the historic long-term average.

Conclusions

This is a strange chapter, even more so in the context of having come across – and been impressed by – Ed’s writings before.

- The discussions around risk – that it is the risk of loss rather than volatility, and is not the driver of returns – are generally illuminating,

- and the corrosive effect of high volatility on compound returns is well demonstrated.

But there is not much to help us as private investors to choose an alternative portfolio at times of arguably high stock and bond valuations (like today).

- Staying out of the markets since the date of Ed’s essay (2005) would have been catastrophic so far.

I have long argued for as diversified a portfolio as can be easily and cheaply achieved (see for example, this article on Meb Faber’s book on Asset Allocation).

- Ed’s article has only strengthened my resolve, even if Ed himself somewhat leaves us hanging in this essay.

Until next time.