A Piggy Bank For Healthcare – IEA on the NHS

Today’s post is about a recent discussion paper from the IEA on how the NHS should be funded. It’s called A Piggy Bank For Healthcare.

Contents

A Piggy Bank for Healthcare

The Institute of Economic Affairs officially has no coroprate view, and so its discussion papers express only the views of the author.

The author of this paper is Dr Kristian Niemietz, the IEA’s Head of Health and Welfare. He studied Economics in Berlin and Political Economy at King’s College London.

Spending

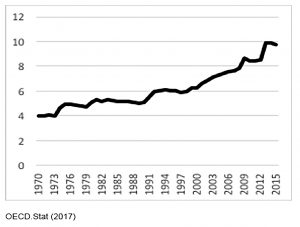

UK healthcare spending has grown from about 4% of GDP in the early 1970s to just under 10% today.

The same is true of most developed countries.

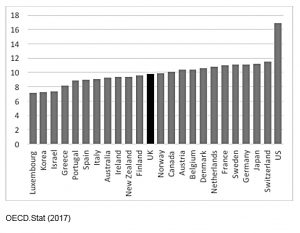

- The UK is in the middle of the range, with the US as a big-spending outlier.

Funding

The NHS (like most healthcare systems, and other UK schemes like the state pension) is funded on a pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) basis.

- Current spending comes from current contributions – no reserves are built up.

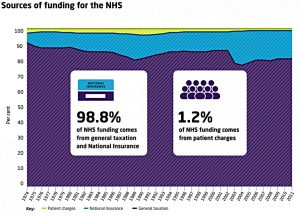

Most of the money comes from general taxation

- But about 20% comes from National Insurance Contributions (NICs)

- And 1.2% comes from charges on patients (prescriptions etc).

Private healthcare

Many healthcare systems provide core services to everyone, with additional services available privately.

In theory that’s the case in the UK, but the boundary between public and private is more rigid:

- the public services provided are broad, and

- “going private” usually involves giving up some NHS care

- to access private care you move into a parallel system, unlike most other countries

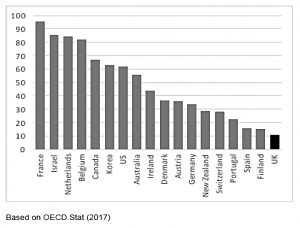

So fewer people in the UK (around 10%) have private health insurance.

Kristian notes that constraining the private sector does not improve the sustainability of the NHS.

- Total healthcare spending is reduced and the proportion falling on the NHS is increased.

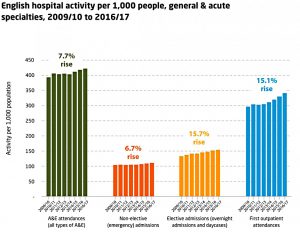

Demand

We could probably spend the entire GDP on diagnostic tests without ever treating real disease – John C Goodman

Though is is easier to control spending in a single-payer system like the NHS, this does not reduce the underlying demand for healthcare.

- Instead, it means that more demand will go unsatisfied.

Like all healthcare systems, the NHS does – and always has – rationed healthcare.

- That’s because health care spending doesn’t have a saturation point.

So the problem becomes working out at what point the “marginal pound” would be better spent on infrastructure, education, or private consumption.

Red herrings

The NHS is a British institution, but the common perception is that it is creaking at the seams.

Kristian is sceptical of the reasons presented in the tabloids and the broadsheets, which he lists:

- obesity

- smoking

- alcohol

- the Private Finance initiative (PFI)

- foreigners

- a lack of foreigners

- new (expensive) medicines

He worries about a cry-wolf effect, where the real problems with the NHS will also be ignored.

The first three, which he classes together as “unhealthy lifestyles” are easy to analyse:

- proponents assume that “if people adopted healthier lifestyles, their lifetime healthcare costs would remain exactly the same, minus the treatment cost of lifestyle-related conditions”

- but in fact such people would live longer, and incur more costs towards the end of their lives

- so unhealthy lifestyles lead to net cost savings – and a moral dilemma

Health improvements used to be a good thing because they extended working lives, but now they “just” extend retirement.

- I suppose it boils down to whether you worship growing GDP or more happy years for more people.

He also disputes that “health tourism” is a real problem.

- most of the costs are incurred on people from the European Economic Area (EEA) or Switzerland, and could be reclaimed with better record-keeping.

- uninsured (poor) people probably account for less than 10% of the £367M (£294M net) cost, or less than 0.04% of the NHS’s £100 bn annual budget.

With PFI, “private companies build and maintain new healthcare facilities, and then lease them back to the NHS for an annual fee”.

Many PFI schemes represent poor value for money … but critics seem to take issue with the fact that PFI payments usually go to private, for-profit companies.

They are making a moral case, disguised as an economic case: they consider the profit motive morally corrupt and illegitimate in the health sector.

The counterfactual to PFI is not a scenario under which those new NHS facilities would have built themselves and maintained themselves for free.

Demographics

What is really driving up healthcare costs (demand) is demographics – rising life expectancy and falling birth rates.

- Unfortunately these real problems allow for less moral outrage.

Demographics will not “bankrupt the NHS” but they could lead to more severe rationing.

- This could mean a deterioration of standards, longer waiting times, greater barriers to access, and a narrower range of treatments.

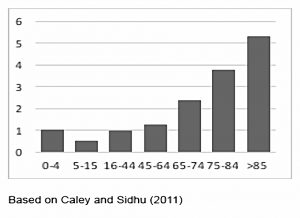

Healthcare costs rise exponentially in old age.

- They are stable to age 50, then double by 70, then double again by 80.

- Healthcare costs of people over 85 are more than five times those of healthcare costs of young and middle-aged people.

Thus demographics (rising life expectancy and low birth rates) work against health spending.

- The ratio of retirees to workers is currently 28%, but will rise to 47% by 2064.

- Those over 85 will rise from 4% of workers to 135.

Government forecasts

The government (the OBR) is forecasting only moderate increases in NHS spending.

- But this forecast depends on a doubling of the NHS long-term productivity growth rate (presumably from technology improvements).

So we probably do have a long-term problem, even if the government won’t admit it.

Coping with demographic pressure

Options for coping with demographic pressure include:

- extend working lives by raising the retirement age

- cut healthcare entitlements

- cut other government spending

- increase the system’s efficiency

- raise the tax burden on workers

The first is happening to a reasonable extent, but the second is unlikely because of the increasing power of the “grey vote”.

The third faces an increasing “anti-austerity” backlash.

The fourth is possible, since the UK always places in the bottom third of the OECD’s efficiency league tables, despite relatively low spend.

- But the leading systems are not particularly similar, so the way forward is not clear.

It is clear that the efficient systems (Switzerland, Australia, South Korea and Japan) don’t look like the NHS, and systems that look like the NHS (Ireland and Finland) aren’t efficient.

- But the NHS’s culture and way of working appears sacrosanct for now.

So that leaves more taxes

- Although as we have previously discussed, the UK is already close to the maximum share of GDP that it can successfully collect as tax.

A sixth option (which could be interpreted as a version of cutting entitlements) is to increase the element of private provision.

This could be done through insurance, or by introducing more charges at the point of consumption (doctor’s appointments, or A&E).

- The latter approach would also have the benefit of choking off some demand.

But the problem then becomes who should pay, and what should they pay for?

- The answer for most UK voters seems to be nobody and for nothing.

The solution

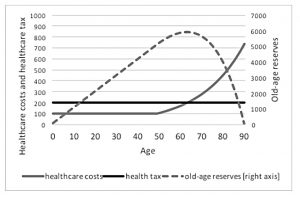

The alternative to our current system of pay-as-you-go is a prefunded system that builds up old-age reserves (like pension funds) during a working life, to be drawn upon when people retire.

The NHS is currently set up as a fair-weather system. Prefunding would mean turning it into a system that saves for a rainy day.

Kristian knows it won’t be easy, quoting the economist Joseph Schumpeter:

A dog is more likely to build up a sausage reserve than a democratic government is to build up a budget reserve.

Note that in the chart above, tax is being collected from age zero – ie before working age.

- That seems impractical, so the tax from age 18 would need to be higher than the 200% shown in the graph.

In theory this system should reduce the demographic issues

- Though since people currently can’t / won’t adequately fund their retirement, it’s not clear how the additional healthcare pot would be accumulated.

Since the funds would need to be invested for many decades, the UK’s savings rate and investment levels would increase.

- This should lead to increased productivity and wage levels over time.

It would also lead to long-term governmental decision making, since decisions about future spending would impact today’s saving rates.

Examples of pre-funding

Theoretical examples of how to approach pre-funding have been developed for the Canadian, the American and the German healthcare system.

- Practical examples are rare, with Singapore and Germany the closest.

Singapore uses compulsory saving into Medical Savings Accounts (this is similar to the Australian superannuation scheme for pensions).

- The balance in an MSAs can be left to descendants on death (and empty MSAs can borrow against their children’s balance).

Germany has two health insurance systems, one of which is prefunded and administered by insurance companies, using smoothed premiums.

- Much more detail on these models and systems is provided in Kristian’s paper.

NHS implementation

Implementing a pre-funding system in the NHS would require a significant tax rise today.

- But this should in theory avoid a larger tax rise in the future (all other things being equal, which they need not be).

The German PKV system has reserves of seven years of expenditure.

- For the NHS, the equivalent would be £700 bn.

- That’s close to 50% of the national debt, and would probably take generations to build up.

The transition from a PAYGO healthcare system to a pre-funded one has never been attempted.

- But the similar (more complicated?) transition from PAGYO to pre-funded pensions has been done.

Kristian would like to see a dedicated NHS tax, partially carved out of income tax (and presumably National Insurance contributions).

- The tax would need to be set higher than current NHS expenditure, in order to build up the reserves.

- Which in turn means a net tax increase (or more “austerity” cuts elsewhere).

The surplus would acrue centrally but be allocated to individuals.

Obviously, people already working (as well as those already retired) would not have sufficient time to acrue the necessary funds.

So this transition period would last for at least 50 years – the time it takes for those not yet in work to reach the state pension age.

- Good luck getting a UK government to think that far ahead.

In the meantime (while there is a shortfall), Kristian suggests plugging the gap with government bonds.

- On paper this would increase the national debt, but in fact it’s just bringing off-balance sheet commitments on to the balance sheet.

I can’t see the point of all this clever accounting myself.

Kristian would actually like to see a move to a multi-payer system at the same time, with insurance companies responsible for building up at least some of the old-age reserves.

- Such systems tend to out-perform the NHS (in health outcomes and efficiency).

- But the political will for such a change seems lacking in the UK.

Conclusions

This has been an interesting thought experiment, but the chances of something like this coming to pass seem very remote.

- While it’s clear that something has to be done about the increasing demographic pressures on the NHS, none of the options seem palatable.

Unlike the state pension problem, where pushing up the line between work and retirement is all that’s required, the asymmetric healthcare costs by age – and enormous variability of lifetime costs between individuals – make the NHS more problematic.

There’s also the moral question of why healthcare costs should be separated out.

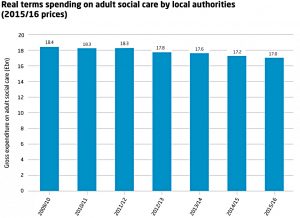

In the narrow context of care, social care costs (for non-acute and / or non-medical condition) are an increasing problem.

- These are funded by local government at present, which means in practice that those with assets fund their own costs.

This disparity between free cancer treatment and expensive Alzheimer’s care is an emotive topic.

- This was demonstrated during the 2017 General Election, the turning point of which was the Tories’ foolish decision to float an increased “dementia tax”.

Thinking more widely, it’s not clear why we should keep score of healthcare costs (contributions and spend) for individuals, but not do the same for all the other public services.

- Education (for you and your children), security (police and military), transport, government, refuse, pensions and welfare are the main services we receive.

- Income tax, NICs, VAT, IHT and CGT are what we contribute.

There are going to be some big individual winners and losers here over the course of a lifetime.

- It’s not clear why we need to balance the individual books on healthcare in particular.

I wouldn’t be against a compulsory pre-funded health care system, but I think that a compulsory workplace pension scheme should be a higher priority.

- And “keeping score” in such a limited area of life makes little sense to me, particularly within a system where the contributions and expenditures are largely outside the control of the individual.

Until next time.

A couple of basic points would need to be agreed –

1) define the NHS – hospitals/dentists/GPs/opticians/care etc what is in or out

2) merge NI and income tax – these 2 sources leave options to funding fudges

Likely with UK demographics (more older/less younger), increased costs of diagnosis tools (scanners etc), increased costs of drugs that additional funding will be required.

My guess is that some NHS-related treatments should be charged – start early and start small amounts but would need to see the breakdown of NHS appointments to see if viable suggestion.

Cannot see how a smaller workforce can pay taxes for all especially with automation on the horizon.