Taming The Lion 1 – Richard Farleigh – Markets & Advantages

Today’s post is our first visit to a book by Richard Farleigh, formerly of Dragon’s Den. It’s called Taming The Lion.

Contents

- Richard Farleigh

- A – Markets

- 1 – Different markets have many useful similarities

- 2 – Trading and investment are increasingly similar

- 3 – Fear the market

- 4 – Markets are mostly efficient

- 5 – Market opportunities are disappearing

- 6 – The markets can overwhelm government intervention

- 7 – The market is strengthened by speculation

- 8 – Most professionals are not outguessing the market

- 9 – Ignore experts and forecasts

- 10 – Understand recent history

- B – Comparative Advantages

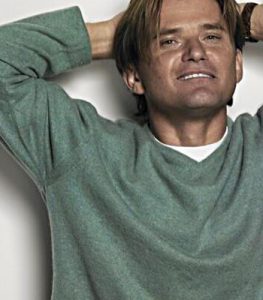

Richard Farleigh

Richard Farleigh will be familiar to most people in the UK for the couple of years he spent on TV’s Dragon’s Den (actually, quite a long time ago now).

Richard studied economics on a central bank scholarship at the University of New South Wales, before joining the derivatives team at Bankers Trust.

- He ended up becoming the bank’s biggest money earner.

In his 30s he was earning millions, but he was headhunted for a Bermuda hedge fund.

- After three years, he retired to Monaco at age 34.

Unlike most of the Dragons, Richard was a regular investor in startups, particularly tech firms, which he began to back in 1995.

- He was also responsible for the restoration of rundown Georgian mansion Home House in Marylebone, and its conversion into one of the most attractive member’s clubs in London. (( I’m not a member, but I regularly attend startup events there myself ))

Richard has now retired once again to Monaco with his (hundreds of) millions, but before he did so, he published this book.

Taming the lion

Richard’s book is more than a dozen years old now, having come out just as he left the TV show.

Its sub-title is “100 Secret Strategies for Investing”.

- Each of the 10 chapters is subdivided into 10 of the strategies.

On reading the book, I felt that the content – which is largely autobiographical and told in the first person – had been shoehorned into this structure.

- So I will be using my own numbering system for the “strategies” (which are really principles), rather than the one used in the book.

That said, it’s an interesting and useful book from a self-made semi-billionaire who has spent a lot of time in the UK.

- As such I think it contains a lot of useful insights for UK investors.

Central beliefs

Richard began as an economist and a chess player, and initially felt that trading was just a form of gambling.

- But he came to believe that prices are predictable.

He developed a repeatable methodology based on a few central beliefs:

- Markets tend to under-react, not overreact.

- Big, obvious ideas offer great opportunities.

- It is safe to invest with a consensus view – contrarian trading is usually irrational.

- It is best to enter and exit the market at the right times instead of always staying invested.

- Price trends are well known but under-utilised.

- Chartists are just astrologers.

- Investment and trading are increasingly similar.

The starting point must be that market prices are normally about right.

Most professionals in the markets are not actually outguessing the price, but are making money from clients, transactions and commissions.

I have used the same methods successfully over twenty years with currencies, bonds, property, stocks and private companies.”

Childhood

Richard was born in 1960 (( Same as me )) in a country town 200 km north-west of Melbourne.

- His father was an itinerant shearer, opal miner and alcoholic, and Richard was the eighth child in the family.

- They lived in a truck, travelling the countryside and camping.

When Richard was two, the children were taken into care and split up, never to be reunited.

- Richard went into foster care in the Sydney suburbs with the Farleigh family.

- He only met his natural parents once as a child, and was not close with his foster father.

A turning point came at the age of 12 when his brother Peter taught him to play chess.

- He quickly became Junior State Champion, and travelled the country attending chess tournaments and developing his confidence.

A – Markets

I have been involved with many different types of markets – I have been a derivatives trader, a bond trader, a currency trader, a business angel and a stock investor.

I have worked for an investment bank, a private hedge fund and for myself, managing my own funds.

The most striking and satisfying thing that I have learnt from this experience is that the different markets have many similarities.

1 – Different markets have many useful similarities

Richard says that in all markets:

- Any genuine opportunity needs to be based on a sound observation.

- Big ideas offer big opportunities.

- Prices take time to absorb information.

- Prices go further than generally expected.

- Prices move in trends.

- Crisis situations and panic buying / selling occur from time to time.

- Investing requires a sensible approach to risk management.

- Analysis requires recognition of both the bullish and the bearish arguments.

- A checklist is very useful.

- Experts are often wrong, and the media oversell how easy it is to make money.

Investors and traders who only look at one type of market can be trapped without big opportunities. They are trying to grow flowers in the desert.

2 – Trading and investment are increasingly similar

Richard doesn’t distinguish between trading an investment, because:

Successful investment increasingly recognises that buy and hold may not work. Markets can move a long way in a short period of time.

Equally many short term trading opportunities no longer exist, and the best may have a time horizon that extends into months.

Richard calls himself a fundamental investor.

Fundamentals are all the factors affecting a market, or supply and demand – social, economic, political or natural.

3 – Fear the market

Richard illustrates this one with a story about trading futures with leverage, so perhaps he means “fear leverage”.

But he has a list of the mistakes he made:

- I started with positions which were way too big.

- I stopped and started a new strategy every few days.

- I had no long term view.

- I didn’t really understand what was driving the market.

- I grabbed profits as soon as I could and stayed with losing positions.

- I listened to the views of other people, including brokers and people with fancy charts.

What Richard is saying is that investing is “a hard way to make an easy living”.

- The market is the lion that must be tamed.

The lion can be tamed, but only by maintaining a healthy fear of the lion.

Be like a lion tamer.

4 – Markets are mostly efficient

Richard also thinks that the current price is usually the right one.

The market acts like a huge super-computer as it absorbs an unbelievable amount of information.

If you believe that the dollar will fall, you think that that the current price is flawed, even though it is the result of a huge amount of people dealing in a huge amount of money.

When I am asked for my view on a market, I’m very reluctant to disagree with the current price.

Of course, a truly efficient market would move randomly – with no trend – as news appears and is discounted.

- But we know that Richard believes in trends.

That’s because he thinks there are two reasons why markets might not be efficient:

- Information is not equally available to all buyers and sellers.

- An example would be a bargain in the property market which exists because too few buyers are aware of the opportunity.

- Buyers and sellers do not sufficiently understand the implications of some information.

- Here an example would be buyers continuing to pay high prices for property when the economy is going into recession.

Illiquid markets are also often inefficient, and misleading information (a la Enron) can lead to inefficiency.

5 – Market opportunities are disappearing

The markets have become relentlessly more sophisticated as the changes that started in the early 80s have continued.

Nowadays, everyone is extremely well qualified, there are computer programs everywhere and there are instant communications.

6 – The markets can overwhelm government intervention

Here, Richard is mostly referring to intervention in the currency markets.

- Older readers will be familiar with the day when George Soros made £1bn betting against the UK government’s attempts to support the pound.

- This was 16th September 1992 – usually referred to as Black Wednesday.

- But since it forced the UK out of the ERM and hence the Euro, Richard thinks it should be called White Wednesday (and I agree).

That even governments cannot reverse the market has always impressed me – it shows the depth and efficiency of the markets.

7 – The market is strengthened by speculation

Speculators add liquidity. Longer term holders of these stocks do not buy or sell very often.

Speculators also absorb risk that others don’t want.

Here Richard is talking about futures markets for eg. commodity prices.

- And if speculators get the price wrong, they will lose money.

The speculator is often just the messenger.

8 – Most professionals are not outguessing the market

Very few [people] are successfully backing their views on markets. They make money in other ways, such as commission and management fees.

More information does not make the market more predictable. The extra information has been priced in.

The critical test is: does the expert make a living out of picking stocks? It’s very easy for someone to have a view with someone else’s money.

9 – Ignore experts and forecasts

You can normally find an expert somewhere to support any view at all.

Beware of the crazy forecaster looking for a publicity stunt. The wildest forecast gets the most press.

10 – Understand recent history

Start by trying to understand what’s happened in the past.

The effort should be in thinking about how prices have reacted to big picture influences in the past few market cycles.

B – Comparative Advantages

These are usually referred to as “competitive” advantages, but Richard perfers the term “comparative” advantage, which comes from economic theory.

- The other commonly used term is “edge”.

11 – You need an edge

If you don’t have a comparative advantage you should not expect to outperform the benchmarks.

The process of being forced to identify a comparative advantage was the best thing that happened to me. My trading had to be based on some sort of logic and discipline.

If you believe that you have an advantage, be very clear what it is. Write it down.

Richard tells a long story about how a big sapphire trade he was financing went wrong, leaving him the world’s largest private holder of sapphires.

- The sapphires need processing before he can sell them on.

- But he lives in Monaco, the sapphires are in the US, and the processing is an artisanal operation in Thailand.

At the time of writing the book Richard had owned the sapphires for eight years, and had no idea what to do with them.

- Never stray from your comparative advantages.

12 – Everybody is a hero in a bull market

It is human nature to attribute our wins to our skill, and our losses to our bad luck.

We know this from our study of Behavioural Investing.

13 – A small advantage is enough to outperform

Richard uses the example of casinos, which have an average edge of less than 5%.

He recommends testing your theoretical advantage – and making changes to the system – slowly.

You really must give the technique a chance to work and not make quick judgements.

Richard classifies advantages under three headings:

- Information

- Original analysis

- Understanding market behaviour

Information is a tracky one for private investors, with face-to-face meetings with executives from smaller companies probably the only potential source of advantage.

- It has also been suggested that consumers have an edge when it comes to consumer-facing products.

- I think this is limited since each consumer only buys a small subset of the available products.

Richard also suggests that looking at the order book can be useful, which for PIs means gaining access to Level 2 data.

- The order book also acts as free insurance for brokers, who can sell their own positions against open client orders when prices move sharply.

The implication for PIs is to try to avoid leaving open orders.

- This is not normally a problem, but can be with smaller, less liquid stocks.

Original analysis was once a rich area for the PI, but the rise of the internet and cheap data and analytical services like Stockopedia mean that we are all singing from the same song sheet these days.

- Once again, smaller companies – which are less studied by the industry – offer probably the best prospects for original work.

14 – Understand market behaviour

Richard is really talking about inefficiencies here, but not the traditional outperformance factors:

- IPOs generally underperform in their early years (see Don’t Invest in IPOs for more detail)

- A flurry of new listings and mergers is a signal that we are at the top.

- Price / sales is a better indicator of future price performance than PE.

- Companies with a lot of media coverage generally underperform subsequently (the “magazine cover” effect).

That’s it for today.

Underlying all of Richard’s strategies are seven themes:

- There remain patterns and anomalies in the markets.

- Markets are slow to react to structural influences.

- Markets move in underlying trends.

- Markets go further than generally expected.

- A view on fundamentals should be combined with price movements.

- Sensible risk management is also required.

- Small companies offer more opportunities.

We’ve covered about a quarter of the book, so we should be able to complete it in another three articles.

- We’ve also covered the first 20 strategies, which I’ve condensed to 14 principles.

Until next time.