Trouble with GDP

Last year we had a couple of posts about the usefulness of GDP as a measure and of constant growth as a pursuit for society. It’s time for a catch up on the trouble with GDP.

Contents

Trouble with GDP

Regular readers might recall a couple of posts from last summer on, respectively, the limitations of GDP and the problems with constant growth.

The Economist led a couple of weeks ago on the same theme, so it’s time for a catch-up.

The story so far – GDP

GDP took off during the Depression in the 1930s, when it supported the prevailing orthodoxy that governments should spend more in recessions to stimulate demand.

- It also came in handy during World War 2, when it allowed the allies to work out how much domestic production could be diverted to the war effort without a country running out of basic goods.

- After the war, GDP was used to work out how balancing spending and taxation could be achieved without creating inflation.

- Membership of the UN came to require calculating your GDP.

Things have evolved slightly since the 1950s, and in the UK at least, inflation and unemployment are now just as important as GDP as measures of national success.

- But the underlying problem remains.

The big problem with GDP – there are others, as we’ll see below – is that it focuses on monetary transactions only.

- If no money changes hands, that piece of work literally doesn’t count.

- This is particularly a problem for work done at home.

- In modern society, that includes things like me writing this blog post. ((The government will pick up on any advertising cost, but that is massively less than the cost of production or the value to readers ))

[Tweet “If no money changes hands, that work doesn’t count towards GDP.”]

The problems with GDP

- free (or DIY) doesn’t count

- primarily because the government cannot tax it

- whereas paying someone to do the same work does

- this includes housework and caring for loved ones as well as the money saved by living in a house that you own

- fixing something broken (eg. a car after a crash, a sick person in hospital) makes GDP grow, but in fact resources have been consumed merely to restore a prior state

- depreciation (wasting) of existing assets is ignored

- beauty and art (poetry and painting) are ignored, as is happiness

- variety and choice (admittedly, too much choice at times) also don’t show up

- bad things (guns, cigarettes, polluting activities) seem good, and negative externalities (on health, or the environment) are ignored

- the black economy (drugs, prostitution, crime, illegal work) is ignored or calculated crudely

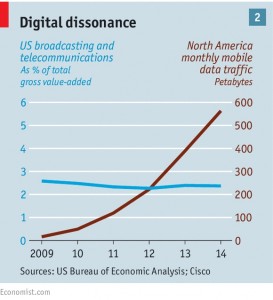

- quality and productivity improvements (the internet, LED lights, faster computers, increased life expectancy, safer cars) are either ignored, or can even have negative effects, if they mean that you can spend less to achieve the same effect

- congestion and the over-subscription of public services are ignored

- it gives government an incentive to spend wastefully, since the cash spending – the cost of provision – is measured rather than its effects (eg. the number of lives saved or improved by the NHS)

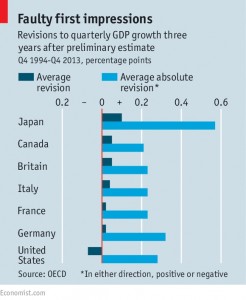

- it’s hard to calculate and frequently subject to revision

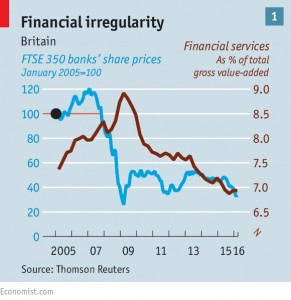

- it doesn’t really work for the financial sector (bailouts boost GDP, many service charges are hidden in spreads, risk is hard to account for as leverage increases GDP)

The story so far – growth

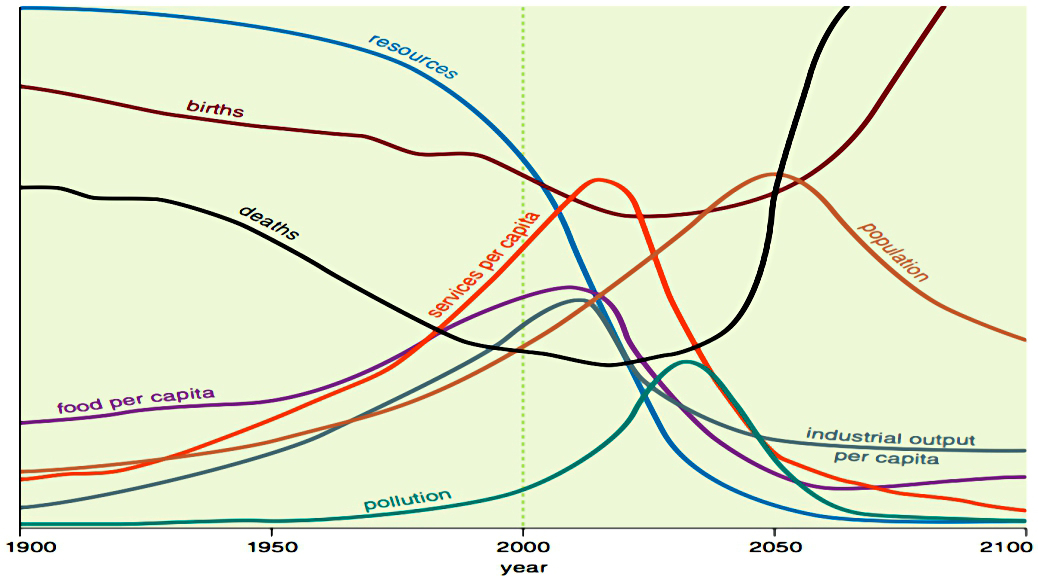

The big question around growth is whether limitless growth of the economy (as currently measured by GDP) is possible.

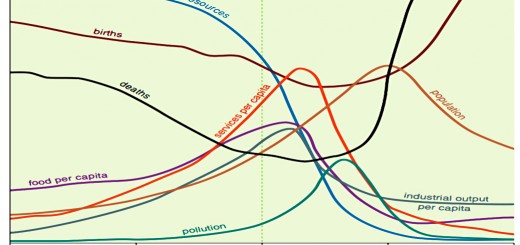

- Doom-mongering dates back 200 years to Malthus, and resurfaced in the 1970s when the earth’s rapidly rising population came into public focus.

Since then the global rate of growth has slowed, but environmental issues like the ozone layer, greenhouse gases and climate change have replaced population as the warning lights of “too much growth”.

- There are also concerns that natural resources and basic requirements for life are running out, or will soon become inadequate or too polluted to use.

- These include oil, water, food and even the biosphere, as more species become extinct.

There are even concerns that “laws of physics” issues like energy consumption will limit growth in the future. ((More accurately these are alternative “planetary resource limits” – we aren’t hitting any physical law boundaries, just running out of planet to use up ))

Admittedly, these limits will take far longer to reach, probably hundreds of years.

It’s also possible that some kind of virtual reality or “desire modification” solution might significantly reduce energy consumption, but this would also limit GDP growth as we currently understand it.

- Or as a halfway house towards sci-fi, we might continue the trend towards more efficient living in bigger and bigger cities.

At the moment, commodity prices have crashed as supply greatly exceeds demand

- Solar energy is falling in cost by 50% per decade.

- Food becomes ever-cheaper and is produced in greater quantities each year.

- And environmental pollution appears to be a temporary phase of early industrialisation.

- London air is now cleaner than at any time since 1585.

So more growth is needed to clean up the planet.

- This may come at the cost of climate change, and it might be better to work towards universal access to drinking water and sanitation.

The cost and speed of light

The Economist begins its 2016 analysis of GDP by comparing the constant speed of light to its price, which varies according to how it is measured.

- Looked at from the GDP perspective – by adding up all the things that people bought to make light – the price of light went up by three to five times from 1800 to 1992.

- But looked at the way a physicist might measure it – pennies per lumen-hour – the price actually fell by more than a hundred times.

This is the quality / efficiency problem in a nutshell.

- The difference in the two implied rates of annual inflation over the 192 years is more than 3.6% pa.

Measuring value-add is hard enough when it comes to “stuff”, but for service-driven economies where the quality of experience counts for more, it is exponentially more difficult (hence the many revisions to GDP numbers these days).

- Facebook, Google and YouTube appear to cost nothing at the point of consumption.

- AirBnb and Uber re-purpose existing assets.

- Free software upgrades renew already-bought hardware.

Inflation

We have written before about the problems with using GDP as the base for inflation.

- As with the cost of light above, variations in how efficiency and quality improvements are interpreted can lead to very different results.

There have been calls to use “hedonic” estimation, which looks at how much people will pay for various aspects of a product (eg. a brighter light bulb), but this is difficult and expensive (involving manual analysis at present).

- And even with hedonics, eventually you are comparing apples with oranges (50″ flat screen TVs with 24″ cathode ray tubes, or smartphones with anything else).

There’s also the price-demand curve to consider.

A product whose price rises will (usually) see its demand and consumption go down.

- It will be substituted with a product whose price has risen less or not at all.

- This means that inflation should be lower than the average price of a basket would suggest.

- Taking the nth root of the product of all the prices in the basket can get around this.

And then we come to services.

How should the value of a meal out be assessed from one period to the next?

- There’s the price difference between the ingredients and staff costs and the final bill paid, but how do service and ambience come into the equation?

- How do you measure the impact of the infrastructure in the town where the meal is being eaten (the bar down the street, the view, or even your fellow diners) or how close together the tables are.

For those who think I’m being too middle-class at this point, similar problems arise with the assessment of phone apps to compare 50 takeaways in your area – of all possible cuisines – with walking down to the fish and chip shop.

With eating out, we’re getting into the position of “positional goods” – things that work by conferring higher status on the consumer.

- How do we work out the value of a Porsche, or a place at the right school?

For me we’ve almost come full circle.

- These things are so subjective that almost the only way to compare them is to use the amount of money that people are prepared to pay for them.

These problems are why the stats say than living standards – adjusted for inflation – have barely advanced over the past 25 years.

Anyone over the age of 40 knows that is utter rubbish.

- The average person in the UK is many times richer than when I was young.

- It just doesn’t show up in the stats.

Fixes

There are no real fixes, but there are a few obvious directions of travel.

One improvement would be to use market-wage estimates to count – probably separately – the impact of activities done for free.

- Reporting these would have to be voluntary, so some kind of incentivisation (like a tax credit) would be needed, which in turn would introduce problems with honest reporting.

Internet traffic could also be used to monitor activity.

We could also come up with more rounded financial numbers that include net worth and depreciating assets, as well as taking account of changes in population and demographics (which have been significant in recent years).

Some measure of the distribution of outcomes – the inequality of incomes and net worths – is probably needed also.

I’d also like to see some thought given to how to measure satisfaction and happiness at work, as that was something that declined significantly during my career, despite productivity and national wealth increasing.

And more effort needs to be put into hedonic analysis, or something even better at keeping up with the evolution of what we spend our money on, and – more importantly – what do with our time.

Conclusions

- Flawed as it is, GDP does appear to contain some kind of measure of human “happiness”.

- The Bhutan experiment to focus on “Gross National Happiness” (GNH) was abandoned when it became clear than many of the GNH values were unattainable for the subsistence farming masses.

- A focus on consumption is wasteful and inefficient, but does lead to rapid innovation and progress.

- It has also been noted that immigration is heavily biased from countries with lower GDP to those with higher GDP.

- There are limits to growth, but they are unlikely to impact our behaviour in my or your lifetime.

- Environmental considerations need not slow growth.

- Climate change will happen, and needs to be adapted to.

It’s also not straightforward to see what could replace GDP, and how such a measure could be harmonised at a regional, national and global level.

The way forward is probably a “dashboard” indication of five or fifty indicators reflecting the complexity and fragmentation – the atomisation – of the age.

- These need to include some kind of market-wage assessment of activities done for nothing.

- These are probably needed not just for countries, but for regions, cities, corporations and individuals too.

Until next time.