UK Private Investor Weekly, 3rd Nov 2014

Welcome to this week’s roundup of of all the financial news that’s relevant to the UK private investor. If you find this post useful, you can find all the weekly updates here.

I have fallen behind with my reading a little, so in today’s weekly roundup I will be covering two weeks of the FT instead of one.

Contents

Fund manager costs

Merryn Somerset-Webb had an interesting piece this weekend on fund manager costs.

She describes a world of 4,000 funds that mostly over trade, overcharge and underperform. She criticises the quarterly performance incentives that encourage short-termism and predicts that cheap passive investments will replace the worst active funds.

I agree with her analysis of the current situation, but the demise of poor active funds has been predicted since I first began to invest and they have survived the introduction of cheaper index trackers and the even more flexible and inexpensive ETFs. Perhaps the advent of DIY investing, encouraged by the recent low-growth environment and an increased focus on costs, will finally make this happen.

Merryn also favours incentives for long-term shareholding (stepped voting rights, enhanced dividends) and the creation of a basic national well-diversified default fund (modelled on the NHS) as a benchmark against which all private provision could be measured.

Ultimately, she would like to see fund managers be more open and responsive to their clients (me and you). Extending the healthcare metaphor, she suggests a Hippocratic Oath for fund managers, where they promise to put the interests of the clients first.

But just as Merryn was attacking high fees, a few pages along, Ken Fisher was defending the status quo. In a market with low barriers to entry, Ken believes that if costs were too high, new entrants would have driven them down. Of course, Ken does run an active management firm.

He notes that alongside a moderate move to passive investments, money has also flowed to specialist active styles (private equity, hedge funds etc), many with higher fees than traditional active funds. Ken’s theory is that people are willing to pay for high service levels because they don’t trust themselves to do the right thing with their investments (chiefly, hold them for long enough, and avoid buying high and selling low). His analogy is with coffee, where all price and quality levels are available (I feel similarly about wine).

He has a point, but I would argue that scaremongering from a self-appointed investment management priesthood is largely responsible for this lack of investor confidence, and rules-based investment is a cheaper solution to the typical private investor’s needs.

I believe in using managed funds for difficult to access markets and assets, and there is certainly a place for independently managed conviction funds, but I can’t see the logic of holding expensive closet trackers – particularly in my home market where information is freely available and trading is easy and cheap.

Financial advice

The FT also carried a feature from Jason Butler of Bloomsbury Wealth on financial advice. As you would expect, Jason is generally in favour of paid-for advice (which is specific to the investor’s personal circumstances, as opposed to the free non-specific guidance to products which is generally available on financial websites).

Don’t buy banks

My final pick from this week’s FT is Terry Smith‘s piece on why banks are a bad investment. In the light of this week’s news that two dozen European banks (none from the UK) have failed their stress tests, this is timely.

Terry used to be a banking analyst a long time ago, so this position may seem surprising. (Co-incidentally, I was working at UBS back in 1992 when they suspended Terry in advance of the publication of his famous book on dodgy financial reporting, Accounting for Growth. The book is well worth a read.)

Terry’s position is that the more you know about banks, the less you would invest. The basic problem is leverage: banks make a mediocre return on equity, but then gear up this return by lending out their assets at a 19:1 ratio. Returns then look fine, but a 5% loss on the assets will wipe out the shareholder’s equity.

This is compounded by the complexity of a bank’s liabilities, which often depend on OTC derivative exposure, and the systemic risk of your good bank being brought down by another bad bank it is in bed with.

Euro-zone deflation

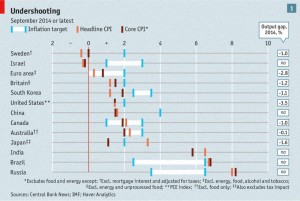

Moving over to The Economist, there was a leader and a briefing on the dangers of euro-zone deflation. The area is vulnerable because of Germany’s insistence on financial austerity and the ECB’s weakness in not implementing QE as in the US and UK.

Prices are already falling in eight European countries. The overall inflation rate has slipped to 0.3% and seems likely to turn negative in 2015 as oil and commodity prices slip. Youth unemployment is above 40% in Spain and Italy.

Europe has lived in fear of inflation for decades, but deflation will be worse. With expectations of lower prices in the future, firms and individuals will stop spending, and this low demand will eventually lead to loan defaults, as in the Great Depression of the 1930s. When nominal wages can’t be cut (since prices are falling too) struggling firms will sack workers (this is a partial explanation of the current high unemployment in Spain).

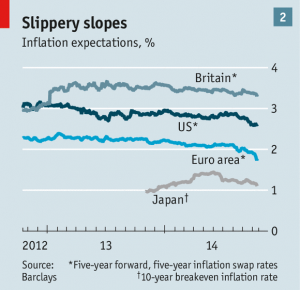

A further issue is stagnating GDP will increase the borrowing costs for nations (as bond-yields increase) which in turn increase the risk of default. Expectations for inflation (estimated via derivatives contracts and the spread between ordinary and inflation-linked bond yields) are already falling.

Unlike Japan, which suffered deflation in the 90s, the euro zone will do so against a widespread background of low inflation. It also lacks the social cohesion to withstand years of falling prices, and the collapse of the euro itself seems probable. With interest rates at close to zero, only QE and money printing are available to the central banks.

The Economist recommends that France and Italy are allowed to slow their budget reductions, and that Germany should take advantage of its negative real interest rates to borrow money to be spent on infrastructure investments. In addition the ECB should buy bonds issued by the EIB to fund cross-border infrastructure (eg. rail links).

Britain’s EU contributions

Although this is not a political blog, this seems like a good place to comment on the news that David Cameron will fight the EU demand for €1.7bn of backdated budget contributions. The bill is due because the UK economy has grown (partly because estimates of drugs and prostitution revenues are now included). Paying more to a wasteful bureaucracy in time of austerity is hard to swallow.

It also seem ridiculous that the UK should be penalised for the success of its economic policies while France (€1bn) and Germany (€800m) should benefit from the failure of theirs. It implies a race to the bottom in economic governance, in the same way that Merkel’s stand on the free movement of labour implies a race to the bottom in terms of welfare benefits.

Divergence

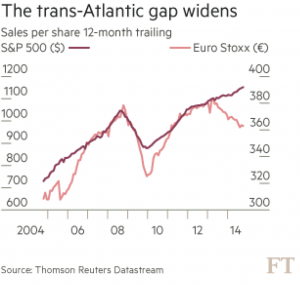

Heading back to the FT, there was an interesting piece ten days ago by John Authers in his regular column The Long View. John pointed out that US stocks have outperformed EU stocks by 61% since the market bottom in March 2009. Is it now time to bet against the consensus that the US will do better than the EU?

Based on cash flows in and out of various ETFs, sentiment against the EU and in favour of the US remains strong. The fundamentals tell the opposite story: US stocks trade at a PE of 26.2 (vs. a historic average of 15.9) whereas the big Euro economies range from 10 to 16, well below their long-term averages. EU earnings are 25% below peak, while US earnings are 50% above the old peak, a new record.

It’s an interesting example of a phenomenon which seemed to have disappeared following the 2008 crash – decoupling. Since then, RORO has dominated, with most asset classes moving in step. But as the deflation debate above shows, the EU has real problems. John himself highlights the recent deterioration in sales by EU companies.

At the same time, the US does look pricey and it seems reasonable that the EU may outperform it in the medium to long-term. But perhaps things will get worse before they get better and perhaps not all of the EU will be around to share in the eventual outperformance. I’d like to see some positive action from Germany, and get past the UK election, with its own implication for EU stability, before I put too much extra money over there.

Alternative invetments

My final two articles are both about alternative investments. David Stevenson, in his FT column Adventurous Investor, wrote about traded life policies and German property. David’s articles are always interesting, and over the years he has introduced me to many of the stocks and funds I still hold.

David is 30% in cash at the moment, and looking for ideas with diversification benefits. Alternative Asset Opportunities is a £27m closed-end fund trading at a 16% discount to NAV. Traded life policies are a form of equity release from the US (traded endowments in the UK were also popular – as individual policies rather than traded funds – when endowment mortgages were in vogue).

Elderly Americans sell their life insurance policies to investors who keep up the monthly payments and receive the payout when the original policyholder dies (hence their nickname of “death futures”). Rising life expectancy means that payouts haven’t been as expected, but the remaining 75 policyholders now have an average age of 90, so the prospects for the next ten years are better. Of course, if a few hold out for another 20 years, return will remain poor.

You may have moral objections to this fund, but even so it remains a good example of a listed vehicle accessible to all (the underlying policies can only be marketed to sophisticated investors) which has no correlation to mainstream asset classes (for our purposes, developed market equities). David is a regular source of such investments.

Taliesin Property Fund invests in Berlin property. David is frank about the problems in the Germany economy and German property but thinks trendy Berlin is an exception. A legal change means that large blocks can now be privatised and split up into individual flats. Taliesin’s flats are valued below the median sales price and are in gentrifying areas.

Neither of these particular investments are for me just at the moment, but they are illustrative of the variety of ideas that David produces. His column is well worth following.

Luxury investments

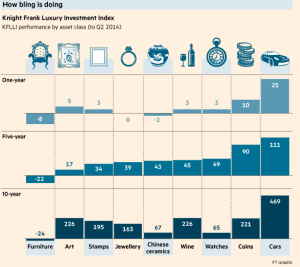

My final choice is a feature on luxury investments by Jonathan Eley. He starts by comparing the returns on the FTSE 100 (still below its 1999 high, though reinvested dividends change that picture significantly) with the Knight Frank luxury index, which has triple the gains over the last 10 years. But alternative assets generate no income, when dividends are included, outperformance drops to 30% over 10 years.

The index covers art, antiques, jewellery, stamps, coins, classic cars and wine, and the key driver of returns is scarcity. Increasing wealth in the BRIC economies is another factor, with lifestyle friendly assets (cars, wine) outpacing coins and stamps.

Investing in the index is another matter. There are few collective investment vehicles, which can in any case only be marketed to sophisticated investors. They are mostly based offshore, have high entry requirements, and cover cars and art. Stanley Gibbons (LON:SGI) operates a portfolio management service for stamps, taking a share of the profits, and there are similar schemes for wine.

Listed vehicles are limited to Stanley Gibbons themselves as a proxy for the stamp market, and Avarae Global Coins (LON:AVR). Other than placing these stocks in a SIPP or an ISA, there are few tax breaks. Wasting assets are exempt from CGT but this basically only applies to cars and wine. Items sold for less than £6K are exempt as chattels.

Transaction volumes are low, and prices and costs are high (many items need special storage or maintenance). More than half of the market is made up of private sales. Items are non-fungible – each one is unique, with its own price. Even the index is only calculated on a quarterly basis. Alternative assets are subject to bubbles, and to changes of fashion which can last decades.

Whilst the decent growth prospects and lack of correlation with major equity indices makes alternative assets an attractive proposition, the practical difficulties and high costs of investment mean they remain unsuitable for the majority of DIY investors.