Weekly Roundup, 10th August 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

House prices and rents

Lucy Warwick-Ching took a look at house prices and rents over the past 5 years. Rents are starting to increase, especially in London – up 3.8% in the year to June, the most since the January 2013. The rest of the country only had a 1.78% annual rise in rents.

But rents still lag property prices. Capital growth rather than rental income has been the main attraction for buy-to-let investors in recent years.

It’s possible that rents may rise further – demand exceeds supply in many areas, and a looming interest rate increase, plus the cap on mortgage interest tax relief, will increase costs for landlords.

It’s also plausible that capital growth will be less strong in the next five to ten years, forcing landlords to look at the rental side of the equation.

Long-term, immigration, population growth and the inability of many young people to buy property should underpin the market, unless the politicians intervene further.

Interest rate rises

John Authers wrote about the prospects for interest rate rises in the UK and particularly the US, in the light of this week’s figures.

The data released by the Bank of England on “Super Thursday” has reduced expectations of an early rise in the UK. Sometime in 2016 is now the favourite.

In the US, things are more complicated. Unemployment was flat at 5.4%, jobs increased by 215K – less than expected – and earnings growth was down to 2.1% pa.

Overall this was a slight improvement, and the chances of a September rate increase were felt to be higher. But there’s no sign of inflation, and a bad jobs report in September could put the rate increase on hold again.

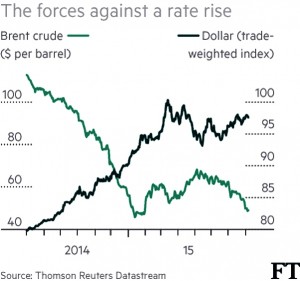

Other candidates for inducing a postponement include the strength of the dollar, which reduces the costs of imports and amount of exports, reducing US inflation in the process. The dollar is up 37% since 2008.

It could be argued that the current dollar strength represents the pricing in of the interest rate rise, but John quotes a Merrill Lynch study of news flow which found that only 20% of the past years gains were explained by monetary policy.

The second issue is falling commodity prices, driven by oil over-production and a slowdown in China. A rise in US interest rates would make things worse, and cheaper oil in particular is likely to be deflationary for the US.

John still expects a rise in September in the US, but then probably a long gap before any further rise.

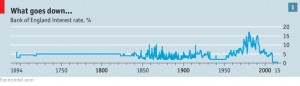

The Economist also had a couple of articles on interest rates. The first began by pointing out that UK rates haven’t increased since July 2007.

Mortgage holders in particular are worried by the potential effects of rises, but they shouldn’t be. The UK has mortgages worth 81% of GDP, which is a lot, and most are variable rate.

If rates rose to 2.5% – which may never happen, or could take a long time – the cost of a 75% mortgage on the average London property (£400K) would increase by £4K pa, or 6% of median pay for London mortgage holders.

But payments are currently only 11% of income on average, and only 4% of mortgage holders are paying more than 40% of gross income. These people are at risk.

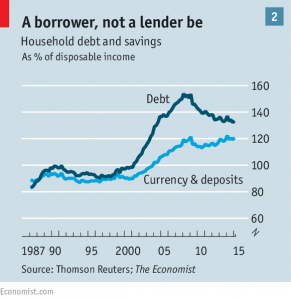

Personal debt is still above savings, so the net effect of higher rates should be lower discretionary spending, exacerbated by the general tendency of those with savings to spend less of the extra marginal income. But the UK has demographics that work in the opposite direction.

Households headed by a 55-64 year-old have 5 times the money and one fifth of the debts as those headed by 16-34 year olds. In countries like Italy the gap is much closer.

These old people spend their money on cruises and the like, whereas young people stash it away. So interest rate rises will not be so deflationary in Britain.

Productivity may not fare so well – higher rates make business investment more expensive. The main hope is that they also kill off “zombie” companies who can survive at low rates, but are not truly competitive. This would increase average productivity and allow wages to rise.

The pound may strengthen, hitting exports but in the process killing more zombies. Unemployment may rise for a time. But eventually there should be benefits.

The second article was about the possibility of setting interest rates according to a fixed formula. Apparently the chair of the committee that oversees the Fed is keen.

The newspaper quotes an 1977 study by Kydland and Prescott which found that tinkering with rates was harmful. They used a simple model where inflation was determined by two factors:

- the pay expectations of workers, and

- the interest rate

Worker’s pay is “stickier” than the interest rate because employee contracts have a fixed duration whereas the central bank can change rates at any point.

In general, the central bankers (the government) will want to keep unemployment low. This will tend to produce inflation, so they will cut rates when wage growth is moderate. But because the expect this, workers will factor the expected inflation into their demands.

The model shows that a credible commitment to do nothing would have better results.

Following the high inflation of the 1970s, the reaction was to make central banks independent, and set them an inflation target. Now workers won’t expect that bankers will create inflation.

Some think that a predictable algorithm would be even better. When deciding to save or borrow, people look not only at today’s interest rate but tomorrow’s. This explains the current fashion for “forward guidance”.

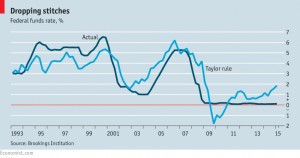

In 1993 John Taylor showed that the Fed behaved as if it was following a rule (now known as the Taylor rule) in any case:

- take the long-term real interest rate (say 2%)

- add inflation

- for every 1% inflation is above target, raise rates by 0.5%

- for every 1% growth falls below “potential” cut rates by 0.5%

This rule mimics the Fed’s behaviour well, and the few deviations have often had negative consequences – the low rates of the early 2000s probably inflated the housing bubble.

In 2009 the Fed has been unable to comply with the Taylor rule since it could not set negative rates.

The rule has its critics:

- long-term real interest rates may now be lower than 2%, due to weak demand and low productivity growth, but there is no consensus on what the rate should be

- there’s no agreement either on what potential growth should be

So the rule would create spurious objectivity, and the Economist is not in favour. I think that predictability is more important than objectivity, and we should give it a whirl.

Charity

In the wake of the Kids Company scandal, Merryn was angry about the cost to the taxpayer of charities. Quoting from a government report with stats for the last 25 years, she worked her way through the various reliefs:

- Gift Aid, where the charity gets 25% back on top or your donation, and a 40$ tax payer gets to claim another 25% back in his end of year tax return – this raised £1.2bn for charities in 2014-15 and saved another £400M in tax for individuals

- Relief on business rates (at 80% to 100%) was £1.6bn

- VAT relief was £250M

- Stamp duty relief on property purchases was £100M

- Inheritance tax relief was £600M

- Payroll giving and other individual reliefs come to £200M

- Corporation tax savings on donations and charities tax savings on investment income and capital gains are not even calculated

- Direct grants to charities from government come to £2.2bn

That’s a total of £6.5bn, and doesn’t include the £11.1bn paid by the government for charities to perform some of their services (outsourcing, if you like, or the Big Society). It’s a lot of money.

Merryn also has some non-taxpayer issues:

- There are 200,000 charities in the UK – too many to supervise properly – with a great deal of overlap

- The proportion of donations spent on generous executive salaries, many over £100K pa

- Some charities (eg Oxfam) spend money on political campaigning, which probably shouldn’t be eligible

She doesn’t even mention the questionable charitable status of private schools and religious organisations.

Merryn wants the good charities turned into quangos and the bad ones to lose their access to tax relief. I agree with her.

Over in the Spectator, Melissa Kite was also unhappy with charities. She told the story of how she signed up years ago to support a child in Armenia.

Over the years the child’s birthday cards didn’t get any more mature, and when Melissa checked she realised that the child should now be 18.

But the charity still wanted the money, even though the only information they could provide – after prompting – was that he was “still in education”. If she stopped sending the money, he could fall in with gangs or take up drugs. Will she ever be able to stop sending cash?

Olive cook committed suicide in May this year at the age of 92, with 27 monthly debits to charities from her account and 180 letters a month asking her to sign up for more.

If you support one charity, they pass your details around to others. You’ve become a soft touch. Your phone starts to ring, and salesmen on commission – not charity workers – will knock at your door. They won’t be checking whether you can afford to donate.

Charities are largely self-regulated at the moment, but the Minister for Civil Society (Rob Wilson) has given them until the end of next month to clean up their act or have new regulations imposed.

Perhaps it’s time we treated charities as part of the financial services industry, and asked them to prove that they can be trusted with our money. ((If you want to find out more about the effectiveness of charities, a good starting point is GiveWell ))

14 years’ hard LIBOR

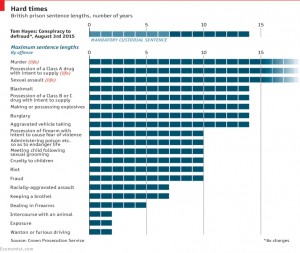

The Economist graphically illustrated the severity of the sentence handed out to Tom Hayes for apparently single-handedly rigging LIBOR.

Only murder, rape and drug-dealing carry a longer sentence in the UK. The judge said he wanted to “send a signal”. Hayes probably didn’t help himself by pleading guilty at first then not guilty later on.

His “following orders” defence doesn’t seem to have been accepted, though I find it hard to believe that nobody higher up knew what was going on.

If he serves half his sentence and is then paroled, it will still be double that served by Nick Leeson for bringing down Barings bank in 1995.

RBS sale – profit or loss?

The government sold a 5.4% holding in RBS for £2bn last week at 330p per share. But all the headlines were about the loss this represented on the 502p per share – £45bn in total- that the previous government had paid to bail out the bank back in 2008.

Ironically, the government has dithered about selling off its stake (still at 73%) to avoid such headlines. With the shares retreating from a high of 400p earlier this year, they appear to have run out of patience. ((Or more likely, they are now able to act without interference from their Liberal Democrat former coalition partners))

The bank was taken over to avoid damage to the financial system, and the massive potential consequences. £1bn is neither here nor there in this calculation.

Unfortunately for the government, they took credit for the profit made from selling off Lloyds shares earlier in 2015. So they probably have to accept the flak for this paper “loss”.

Bosses’ pay

Over in the states, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has approved rules that will require public companies to publish the ratio of their CEO’s pay to that of their median earner.

The pretext is that shareholders want to reign in executive pay, and the Dodd-Frank act requires this. In practice the lobbying came from trade unions who want to see bosses paid less and their members paid more.

There’s an argument that this is not the right measure. Investment banks with high pay generally might score better than more basic firms with a boss on a modest salary.

There’s also the possibility that some low-wage workers may lose their jobs, to bring the median up a little.

But it’s a big step forward from where we are now, even if it’s for the wrong reasons. We could do with a similar rule here in the UK.

Buffet fund

A few days after I looked at my first annual letter from Warren Buffett, MoneyWeek (via Investors Chronicle) was pointing me at a fund to match his investing style.

Trojan Global Equity fund is managed by Gabrielle Boyle, who favours durable consumer brands with strong distribution channels. “We don’t own cyclical businesses or companies that are dependent on one or two products.

The fund has only 31 holdings, including Colgate-Palmolive, Nestle, Microsoft, Novartis and Roche. The fund has 47% in the US, 20% in Europe, 5% in Asia and 5% in the UK.

Boyle also dislikes excessive turnover in a fund, and caps her own at 20% a year. The fund has outperformed over 1 and 5 years, but underperformed over 3 years. The fund’s ongoing charge is 1.12%.

Funding the BBC

Over in the Spectator, Rory Sutherland had a good idea about how to fund the BBC:

- half the licence fee and use it to fund “the BBC’s Reithian purpose” ((I personally think the Reithian ideals need an overhaul: entertain should be removed so that the BBC has no excuse to produce shows like Strictly and The Voice))

- the other half could be paid as a digital currency (“Beebcoins”)

You could buy more Beebcoins, to spend on content from the BBC or its media competitors.

Though this sounds like the BBC would lose out, in practice they would probably make more money from the premium services. More choice tends to mean more spend.

The problem the BBC faces at the moment is that people don’t like to pay for things they don’t want or need, especially when they are bundled with things that they do like.

The BBC’s output is so broad that everyone hates something that it makes. and that’s the thing that people think of when the licence fee renewal drops on the doormat.

Rory quotes an experiment where people were asked to bid for nice pens. ((I’m guessing the experiment was a few years ago, as the attraction of pens has decreased recently)) The average bid was $30, but if a crappy ballpoint was added to the pile the bids went down.

Annual billing wouldn’t work for mobile phones ((Except for the wealthiest)) or for coffee shops any more than it does for the BBC.

People should be able to buy programmes and articles one at a time, and for this we need micropayments of 5p and 10p. To prove that the technology is already available, a QR code to send Rory 1p worth of BitCoin was printed next to the article.

I’m a massive fan of micro-payments, though BitCoin may not turn out to be the solution. For one thing they might help to keep this blog afloat.

So don’t be surprised to see a QR code at the end of next week’s article.

Until next time.