Weekly Roundup, 18th August 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells a Story.

Contents

Funds vs fund platforms

Judith Evans compared the performance of shares in the four major UK financial service companies over the past five years, with that of the typical UK equity fund that they offer to their customers.

The chart actually came from Boring Money, a new and jolly consumer-watchdog style UK website with the slogan “Smart Investing for Normal People … because smart investing shouldn’t just be for The Old Boys.”

The four companies are:

- St James’s Place, a “wealth manager”

- Hargreaves Lansdown (HL), a fund platform

- Legal & General, an asset manager and insurer

- Standard Life, another asset manager and insurer

The performance of their shares was compared to the popular Invesco Perpetual Income fund, and to the average of UK All Companies funds. All four of the shares did much better than the funds.

The fear is that this outperformance reflects high fees. Unsurprisingly the companies disagree.

HL is a pretty obvious story – they were early market leaders in the “friendly” fund platform arena, and as the financial reforms of recent years pushed more investors in this direction they have grown rapidly.

When everyone else was even more expensive (10 to 15 years ago), HL’s fees were less of a concern, but they now seem high, and I probably wouldn’t open an account today.

I would expect firms like AJ Bell YouInvest to give them a run for their money in the future, and I suspect that the shares won’t outperform by such a margin over the next five years.

St James’s Place are more of a mystery to me. Many of their funds are chronic underperformers that regularly appear on the “Spot the Dog” lists, but people still seem happy to support them.

Personally, I think that the era of open-ended funds (OEICs or unit trusts) is coming to an end.

ETFs are more flexible and liquid, and investment trusts have their own advantages. For the long-term investor, individual UK shares can work out cheaper, too.

Perhaps it’s time to sell these shares, if you have any.

Charities as investments

Judith also wrote about the continuing fallout from the Kid’s Company charity scandal. Donors have been advised to “think like investors” and scrutinise charities’ finances, to defend against potential financial mismanagement.

UK individuals give more than £10bn a year to charities, mostly on the basis of personal connections, well-known brands or “anecdotes and moving stories”, according to Don Corry, CEO of the New Philanthropy Capital consultancy.

Charities must be able to explain the impact of what they do and how they tell if it works, said Caroline Duckworth, chief executive of Quartet Community Foundation, which matches donors with charities in the west of England.

A charity’s accounts can be found on the Charity Commission website:

- As Kids Company showed, low cash reserves can be a warning sign, whereas high reserves beg the question of why the charity needs money.

- “Good practice is to hold between three and six months’ worth of reserves,” says Ms Duckworth.

- Charities should also be able to demonstrate they are not overly dependent on one source of income, said Mr Corry.

- High staff costs are another potential issue.

- Rapid staff turnover is another red flag, as are high ratios of staff to beneficiaries.

China’s devaluation

John Authers looked at the impact of China’s largest currency devaluation (1.9%) for 20 years. The initial reason for action was clear. The day before, China announced awful export numbers – down 8% year on year.

So it looked like a currency war – China wanted its exports to be cheaper than other people’s exports. ((The other thing that this devaluation will export is deflation to the developed world – the much-discussed interest rate rises in the US and the UK now look slightly further away )) With low interest rates everywhere, China’s advantage is a huge stack of FX reserves with which to enforce any exchange rate it chooses.

With a further 1.6% fall the next day, the theory seemed confirmed, and companies with any reliance on sales to China – even Apple – saw their stock prices fall.

The the renminbi started to go back up, and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) intervened against another fall. PBoC stated that its actions were preparations for allowing the renminbi to float freely on world markets.

China wants its currency to form part of the IMF’s special drawing rights, but floating at the moment would force the currency too low.

As this became clear, the sold-off stocks rebounded, and bonds and gold sold off again. Things went back to the way they were before. But commodity prices continue to fall. Oil hit another post-crisis low, as did copper.

And the stocks most reliant on China struggled. The 48 largest developed market stocks that get at least 30% of their sales from China have fallen 10% since June, in flat markets.

Few people believe China’s official GDP growth rate of 7%. Other measures – such as rail freight, electricity production and housing starts – suggest a decline.

The impact on foreign suppliers of commodities is increased by a shift from construction and exports into internal services.

Despite the PBoC’s intentions, the failing economy may force a genuine devaluation in the end.

Automation and jobs

The Economist looked at three papers on the subject of automation and jobs in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

The fear that jobs will disappear dates back to the Luddites and the first factories of the industrial revolution.

Worries typically focus on substitution, where jobs once done by people are taken over by machines. Currently the prospect is of versatile robots taking over on a scale never seen before.

The first paper reassures that many new jobs will be created by automation. It is always easier to identify the disappearing but familiar work than to imagine new kinds.

The share of America’s population in work rose during the 20th century despite technological advances, and the reduction in the farm workforce share from 40% to 2%, did not produce mass unemployment.

Between 1980 and 2010, the number of US bank clerks increased. Cashpoints freed them up to sell extra financial products to customers.

The second paper argues that we are seeing a revolution, and a “Cambrian moment” for robots is just around the corner:

- “Cloud robotics” where robots learn from one another, and “deep learning”, where robots process vast amounts of data to form associations that can be generalised, will produce rapid growth in competence.

- These trends will be supported by the exponential growth in the availability and capacity of wireless internet, data storage and processing power.

Driverless cars are the poster child for this argument.

At the moment, automation threatens cognitive but routine tasks in administration and middle management:

- Employees whose work is cognitive but not routine have in general gained from technology, since it enables them to process and present information more quickly and easily.

- Lots of manual labour has also been difficult to computerise.

This has led to the “hollowing” of work, with more jobs at the top and the bottom, but fewer jobs in the middle. This may be about to change, with all types of work now vulnerable.

Detractors argue that “tacit” knowledge needed for high skill jobs can’t be learned by machines, and also that robots will be restrained politically, as their impact on jobs and society becomes clear.

The third paper looks at the history of automation angst, and focuses on the difficulty of spotting the new jobs.

Overall the Economist is not too worried, but regular readers will know that I am.

I’m always wary of saying “this time it’s different”, but omnipresent internet and cheap as chips clever robots are a long way from the spinning-jenny and the combine harvester.

The Luddites and their peers eventually found jobs in the factories, but today’s unskilled workers in particular are starting to look like buggy whip manufacturers, or even all those horses that pulled the carriages.

The challenge of the next twenty years is to come up with an alternative to the glue factory.

Bitcoin fork

The newspaper also reported on a spat between developers that might result in a split in the digital currency Bitcoin.

Over the weekend, two of Bitcoin’s five main developers released a competing version (a “fork”) of the software that underlies the currency.

The dispute is over the size of a “block”, a batch of Bitcoin transactions ready for processing. The original creator – who “went dark” in 2011 – limited blocks to 1Mb, enough for around 300K transactions per day.

This prevents mainstream use of the currency – Visa and MasterCard can process tens of thousands of payments per second.

One camp within the Bitcoin community (two developers plus supporters) wants to set the number much higher right now. The current system is on track to run out of capacity next year.

The other group (of three developers plus supporters) worry that this will centralise the currency, making more like a normal payment system.

There has recently been a decrease in the number of “nodes” – computers that check whether blocks of transactions are valid – and increasing the block size could accelerate this.

There is a process to settle such disputes but it is slow and relies on consensus. To force a decision, the developers of the new fork (Bitcoin XT) have asked “miners” to vote by installing the new version.

Reddit moderators have censored mentions of Bitcoin XT as an effort to undermine the community. The debate, like so many others, has therefore moved to the uncensored Voat.

When (if) 75% of nodes run Bitcoin XT – and no earlier than January 2016 – it will upgrade to an 8Mb block. Nodes running plain old Bitcoin would then be locked out. The plan is to then double the block size every two years.

After one day, 8% of nodes had installed XT. Watch this space.

Short-termism

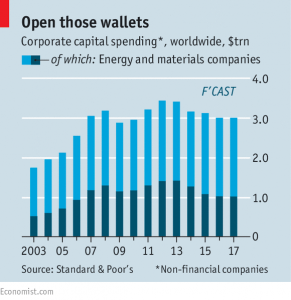

Buttonwood wrote about how corporate short-termism might be caused by the way that investors employ fund managers.

Business investment has been disappointing since the financial crisis, and is expected to fall by 1% this year,and a further 4% in 2016.

This would make four straight years of decline, despite very low interest rates designed to encourage borrowing and investment.

The current fall is largely driven by the commodities bust, plus general fears about falling demand in the global economy.

The energy and industrial materials sectors largely to blame. Without them, capex would rise by 8% this year. But those sectors are difficult to ignore – they accounted for 39% of capex in 2014.

But there may also be a structural factor. Businesses are too focused on short-term profit targets and not enough on long-term returns.

This approach is driven by shareholders, who demand cash in the form of buybacks and who turn over their portfolios much more quickly nowadays. The average holding period in the US and Britain has dropped from six years in 1950 to less than six months today.

This was termed “quarterly capitalism” in 2011 paper by Andrew Haldane and Richard Davies. They found evidence of short-termism in stock prices, with investors applying excessive discount rates to their estimates of future cash flows.

Another paper co-authored by Haldane suggested that public companies invest less than similar private companies, due to shareholder pressure. He suggested changes to executive pay and extra votes for long-term shareholders.

Paul Woolley – a former fund manager, now at the LSE – wants instead to change the contract between investors and fund managers.

Since investors can’t be certain of a manager’s skill, they judge on past performance, which may be luck. Comparison to a benchmark is supposed to remove some of the luck, but results in “active” managers hugging the benchmark (acting as “closet trackers”).

This can lead to mispricing as stocks that have done well (and may be expensive) are chased higher by fund managers. This in turn partly explains the momentum effect.

Woolley has five suggestions:

- a benchmark based on cash plus inflation or cash plus GDP growth

- using long-term value investor funds rather than expensive “absolute returns” hedge funds

- assessment over 5 years or longer

- using the volatility of cash flows (dividends and interest payments) rather than volatility of portfolio value as a measure of risk

- using a maximum turnover measure (100% pa or less)

If fund managers were encouraged to be patient, companies could invest for the future. The trick now is to get investors – and particularly institutional ones – to think long-term.

Capitalism

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=1849548684&template=thumbnail]

The Economist also reviewed a new book by John Plender called Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets.

In recent years, critics from Occupy Wall Street to the Pope have criticised capitalism as exploitative. They worry about the impact of economic inequality on social cohesion.

Plender’s book shows such complaints date back to Socrates, and run through Moliere, Zola and Dickens to Gordon Gekko in “Wall Street”.

But for all its faults, capitalism has raised the living standards and life expectancy of billions of people since the 18th century.

A lot of recent criticism stems from the 2008 crisis. Capitalism now means high finance, rather than Victorian entrepreneurship or the inventions of Edison. And it’s clear that lots of the bankers have been rigging the system.

Plender fears another great financial crisis – banks are bigger and more interconnected than ever. But capitalism will muddle through and adapt as in the past.

Echoing Churchill’s words on democracy, he concludes that “capitalism is the worst form of economic management, except for all those other forms.”

Stock market sizes

We end this week with a map from Bloomberg that I came across on Twitter. It shows the world as it would look if countries were the same size as their stock markets.

The UK does quite well out of this, coming third after the US and Japan. Larger countries from the real world (Canada, China, Russia, India, Australia) are harder to pick out on this projection.

Europe is middling in size, and much of the emerging markets – especially South America – almost disappear. Africa is invisible apart from South Africa.

We can dream, can’t we.

Until next time.