Weekly Roundup, 1st March 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

Who suffered most?

Adam Palin asked whether the financial crisis actually hit the rich hardest. He compared the change in disposable incomes of UK households (after tax and benefits) since 2008.

- Surprisingly, all but the poorest fifth became worse off.

- These were 5.8% better off in real terms.

Most of the relative benefits came early on.

- Between 2007 and 2012, the real net income of the bottom fifth went up by 2.7%, whilst that of everybody else fell.

The minimum wage and tax credits are largely responsible.

- Child and working tax credits rose from £20 bn in 2007/08 to £30bn in 2012/13.

Pensions are also relevant.

- A lot of the poorest fifth are retired, and their incomes have been rising, partly due to the triple lock on the state pension.

The top fifth did worst, losing 7.9% or £4.4K pa from 2007/08 and 2012/13.

- The 50% band of income tax was introduced,

- and the personal allowance has gradually removed for those earning above £100K pa.

- More recently, child benefit has been withdrawn from high earners.

Since 2012/13, everybody has been doing relatively well, with salaries rising and inflation low.

- The top fifth is now only 3.3% down in real terms on 2007/08.

Despite what the media would have you believe, income inequality has reduced slightly since 2007//08, continuing the trend dating back to 2001/02.

- The Gini coefficient reached a 27-year low in 2013/14 but remains higher than in the late 1970s.

Wealth inequality remains high, driven by house price inflation in London and the South East.

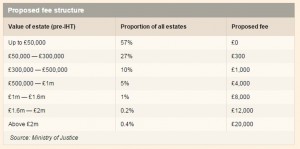

Probate fee increases

Adam also reported on a massive increase in probate fees.

The new charges do seem extraordinary, though they are concentrated at the top end of estates, and never rise above 1% of the estate.

- Lots of ordinary families with houses in London and the south-east will be affected, though.

- And they will have to find the cash up front before they can liberate the assets from the estate.

It does seem a bit of a cheap shot – if the government wants to raise more money from the dead it should change inheritance tax rules.

- Charging a grieving relative £20K to print a few forms is not cricket. ((Disclosure – I was the administrator for my Dad’s estate a few years ago, and paid about £200; always do it yourself – my Dad’s bank wanted thousands for filling in a few forms and writing a few letters ))

G20 policy flop

Elsewhere in the FT was a report on the failure of the G20 to agree at their Shanghai conference on coordinated policies to stimulate the world economy, as urged by the IMF.

- Bones of contention included negative interest rates and even the need for further stimulus.

German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble was particularly negative (surprise, surprise).

- French finance minister Michel Sapin was almost as doomy.

- The group looked mainly to China to provide more stimulus.

Mark Carney was widely reported as calling negative interest rates a “zero-sum game”.

- The policy can work for an individual country – via an exchange rate mechanism – but exporting excess saving and demand weakness does nothing for the world as a whole.

- In fact, it causes liquidity problems and increases the threat of deflation.

No sign of helicopter money at the global level, then.

Base rate guessing

Tim Harford looked at how to make good guesses. He started with an old chestnut about probabilities:

- Is someone reading the FT more likely to have a PhD or no degree at all?’

It feels like brainy PhDs will read the FT, but think about the numbers:

- less than 1% of people in Britain have a PhD

- 75% of British adults have no degree

So it obviously more likely that a reader of the FT has no degree.

Combining two pieces of information like this requires the use of Bayes’ rule, and most people are bad at it.

The problem is called “base rate neglect”, and it’s driven by “representativeness”.

- People latch on to the most “relevant” fact and ignore things that are actually much more important.

When forecasting the future, the base rate is very important.

- You may have good reasons to depart from it, but it’s the best place to start.

Tim uses the example of forecasting whether there will be a recession in the UK during 2016.

- He gives this a 10% chance since there have been 7 recessions in the past 70 years.

His second example is of cancer risk.

- Eating bacon might increase the risk of bowel cancer by 18%,

- but if the base rate in the population is 6%

- then bacon is only causing one extra case per 100 people,

- which most people would call a 1% extra risk.

The third example is disease screening.

Let’s imagine a test that is 75% accurate (false positive the other 25%).

- If you take the test, you might think there’s a 75% chance you have the disease.

- But without the base rate, you don’t know the probability.

Let’s say that 4% of the general population have the disease.

If you test 100 people, then:

- 3 people with the disease will have a positive result

- 1 person with the disease will be given a false negative

- 72 of the 96 people without the disease will test correctly negative

- the other 24 without the disease will have a false positive

Of the 27 positives, only 3 – 1 in 9 – are really positive.

- So you would only have an 11% chance of having the disease after a positive test.

Always check the base rate before making your guess.

US earnings estimates

John Authers looked at US corporate earnings:

- profits for S&P 500 companies fell 3.5% in 4Q2015

- energy company profits fell 74.5%

- utilities, industrials and materials companies also had profit falls

Forecasts for 1Q2016 now show a 5.7% decline, down from predicted growth of 2.3% on 1st Jan.

- In Europe, earnings declines of 1.2% and revenue falls of 5.7% are expected.

- Earnings estimates for the constituents of the MSCI World index are now 12% lower than last summer.

Broker estimates tend to be optimistic, as this sells stocks.

- But the direction of travel is downwards,

- and it is the companies themselves – who should have a good idea of their immediate future – that are talking down the estimates.

John also notes that the gap between GAAP and adjusted numbers for US companies has widened, implying deliberate manipulation of accounts.

- The gap for earnings in 2015 was 29.5%, close to the 28.6% gap ikn 2007.

- By 2013, the gap was down to 9.5%.

Stocks tend to follow GAAP numbers in the long run, not “pro forma” profits.

- And even the GAAP numbers have been boosted by share buybacks and M&A.

John isn’t expecting a crash in the US – recent economic data has been better than expected, and there should be no recession.

But new highs are unlikely.

- The S&P 500 PE is 17.5, down from the 2015 peak of 18.9 and close to the average since 1954 of 16.4.

- But on GAAP earnings the PE to 21.5, a level usually seen near market peaks.

- And until 2003, PEs were based on GAAP.

So the outlook in the US is not good.

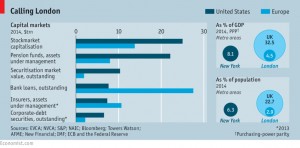

London is too small

The Economist came to the counter-intuitive conclusion that London is too small.

It’s already awkwardly big to suit most of the UK

- two-thirds of non-Londoners think that London is good for Britain,

- but less than a third thought it helps the place that they live.

The rejuvenation began in the 1980s with the deregulation and globalisation of finance.

Skilled workers and productive companies are drawn to London from the rest of Britain and the rest of Europe.

- This gives the city an unbeatable productivity advantage.

London has 23% of the UK population and a third of its economic output.

- It is the fifth-largest city economy in the world, and the EU’s largest city by population and output.

But London has only 4.5% of the EU’s output and 2.9% of its population.

- New York has 8.1% of America’s GDP and 6.3% of its population.

Whether London will ever grow to this size depends on the future of European integration, and to an even great extent, on the result of the Brexit referendum.

- I wonder what the inhabitants of Paris, Frankfurt and Milan think about this?

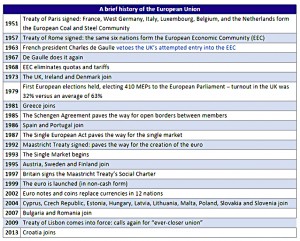

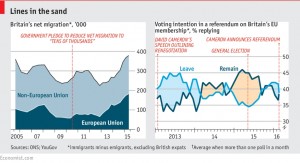

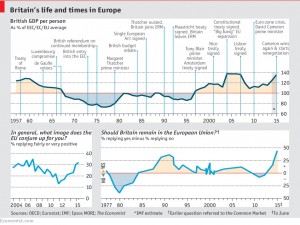

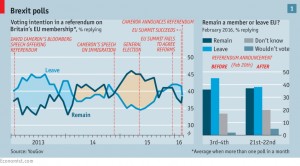

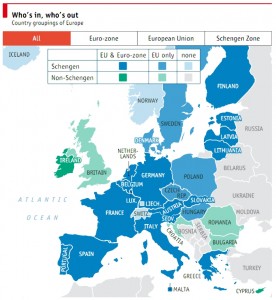

Brexit

Which brings us nicely to the main event of the week.

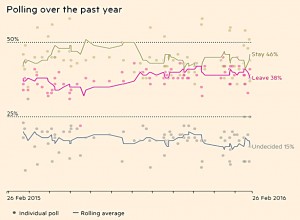

Now that David Cameron has fixed the date of the referendum for June, everybody was talking about Brexit:

- there were two articles in the Economist (1 and 2)

- three in MoneyWeek (1, 2 and 3)

- one in the FT

- and one in the Spectator

This one will run and run, and I don’t expect to reach any conclusions today.

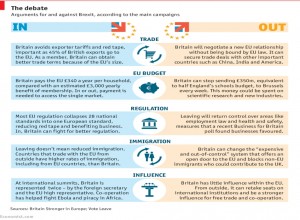

- Nor will I run through those seven articles in detail.

- Instead, we’ll do a bit of scene-setting, and lay out the major issues, and the key arguments for and against Brexit.

The Spectator was in favour (of Brexit).

- It saw Cameron’s struggle to negotiate a new deal for Britain as symptomatic of the EU’s problems:

- If one country has a good idea, the other 27 demand a price for agreeing, or they want concessions which mean the final change is a fudge

- The big problems facing the EU are immigration and a potential new banking crisis, and EU policies won’t help either of these.

- Europe’s welfare policies are not compatible with open borders and mass migration, even from within the EU.

- But Cameron’s idea to ban migrants from welfare is resisted.

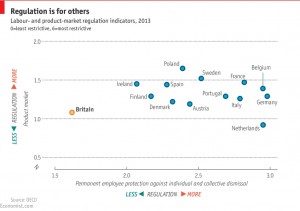

- The EU has failed to open up the single market in services, for fear of the UK swamping the continent.

- And the EU has not succeeded in opening up trade with the rest of the world (no treaty with Japan, for example).

- We continue to subsidise farmers not to produce food.

- The euro is unsustainable.

- And the leaders of the EU are committed to “ever-closer union”

- They have no intention of returning to a simple free trade bloc.

MoneyWeek was also in favour of leaving:

- The EU is an undemocratic leviathan.

- It is reactive rather than proactive (Greece, the refugee crisis).

- Ever closer union and the euro are doomed projects.

The only question is whether to try and reform the EU from within, or take the risk of leaving.

The risks of leaving include:

- less trade

- fewer jobs

- disruption to financial services as banks move functions to the continent

- another Scottish referendum (that would vote to leave this time)

- a weaker pound, driving up the costs of imports

The potential benefits include:

- more trade

- we have a deficit with the EU that they would like to retain,

- and there would be more opportunities further afield as emerging markets grow again

- less red tape

- only 5% of UK small businesses export to the EU, but they all have to follow EU regulation

- improved control over immigration

- laws would be written in Westminster rather than Brussels

- £10bn in annual savings from not making contributions to the EU

The FT article focused on the separation process, and the practical difficulties of unravelling 40 years of membership.

- It seems that although Britain can vote to leave the EU, it would have no input to the exit terms, which would be up to the other 27 members.

The Economist was in favour of staying in though it recognised that Cameron may struggle to win his referendum.

It’s hard to judge what might happen after a vote to leave since Greenland in 1985 (which remains a dependency of EU member Denmark) is the only precedent.

- Brexit would trigger an application to withdraw under article 50 of the Lisbon treaty, which provides for a new agreement with the withdrawing country over two years.

To the Economist, that sounds like a divorce demanded by one partner, with the terms fixed by the other.

- It could be slow, difficult and unfavourable for Britain, especially as our departure would destabilise the whole union, which is already in trouble.

- Prolonged uncertainty will discourage foreign investment in Britain.

And the route to future trade with the EU is not clear.

- Norway and Iceland use the European Economic Area (EEA), but this means following EU regulations, making payments (Norway pays 90% per head of Britain’s payment per head) and free movement of EU migrants.

- That doesn’t sound like the deal that the UK wants.

- Switzerland has bilateral agreements for goods but not services and has almost the same responsibilities.

- South Korea and Canada have better deals, but they don’t cover financial services.

Britain would also have to replace 53 EU deals to which it would no longer be a party, including America, China and India.

- This will take a long time,

- and after 40 years in the EU, Britain lacks trade negotiators.

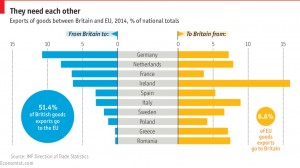

Nor can the trade deficit be relied upon to force matters:

- Britain accounts for only 10% of EU exports while the EU takes almost half of Britain’s.

- And most of the British deficit is with Germany and Spain.

- Would the other 25 members be in a hurry?

That’s probably enough about Brexit for today. More to come next week, no doubt.

Until next time.