Weekly Roundup, 20th February 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the various stock indices in China.

Contents

Chinese stock indices

Kate Beioley looked at the differing returns over the past two years to the various stock market indices available in China.

- A-Shares are listed in Shangai or Shenzen, and foreign participation is limited.

- H-shares are listed in Hong Kong and are easier to buy.

The A-share market is much bigger, has 80% private investor participation and is very volatile.

- But some of the hottest stocks have only A-shares.

The H-share market is more stable and where stocks are dual listed, the price in Hong Kong tends to be lower.

- There H-share market has a tech bias, whilst A-shares are mostly smaller, and contain more financials and industrials.

The best performing index is the MSCI China, which comprises 152 large and mid-caps and includes 82% of Chinese stocks listed on foreign exchanges.

- IT makes up 40% of the index, which is up 136% over ten years.

The worst performer over ten years is the China A index.

- This has 800 holdings but is dominated by a big insurer a large bank.

Over five years, the FTSE China A50 comes top.

- But over one year, MSCI China is top again.

Generally A shares are more volatile than H-shares.

- A shares will join the MSCI Emerging Markets index in June, which will cause tracker funds to buy them.

This may reduce their volatility.

Still in a bull

Ken Fisher was back with the latest installment in his “we’re in a bull market” series.

- He sees the 10% fall in the S&P as a “model-conforming correction-type shock”.

Over the 92 years of the S&P 500, there have been 49 falls of more than 8% but less than 20%.

- They lasted between one and eight weeks.

Real bear markets start “slowly, softly and quietly”.

- And they have bad real world outcomes – recessions or global wars.

Two-thirds of a bear market’s percentage drop comes in the final 30% to 40% of its duration.

Ken has a rule (from a book he wrote in 1987) that you can’t call a market peak until three months after it happens.

- This has worked for all bear markets in global stocks.

I’m a big fan of the three-month period myself (along with the classic 10-months) – though I tend to use moving averages rather than look for peaks.

Bond yields and the dollar

John Authers reported that higher US bond yields were failing to stop the deterioration in the dollar.

- The US 10-year yield rose to 2.9% this week.

Yet the dollar, which rose during the market volatility at the start of this month, is now back at its lowest level since 2014.

- That’s despite the gap between US and German yields rising from 1.7% last summer to 2.15% today.

The weak dollar flatters US firms’ foreign earnings, and makes exports competitive.

- It’s also good for emerging market nations, who often borrow in dollars.

- It’s not so good for rich-world exporters like Germany and Japan.

To add to this, the Chinese are buying fewer US bonds (pushing their price down and yield up) and the people John calls “bond vigilantes” are wary of US bonds because they expect inflation to puch yields higher.

- Gold rises also imply fear of inflation, but also no fear of an over-zealous Fed that rises rates so fast that it creates a deflationary environment.

John agrees with Deutsche bank that 3% bond yields will be be needed to trigger a major shift in asset allocations.

- Until then, stocks and gold will do well, and bonds and the dollar won’t.

For an alternative view, I’ve heard a lot of chatter over the weekend that the bottom is now in for the dollar.

And Pimco – the world’s largest bond fund manager – have said that the top is in for US bond yields.

We live in interesting times.

More tax, please

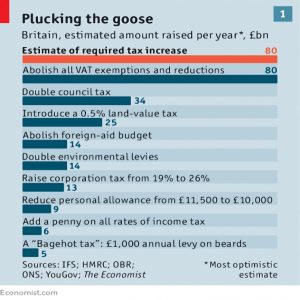

Being a leftist newspaper, the Economist has decided that the annual NHS “winter crisis” and an increase in the number of rough sleepers means that we have a fiscal deficit that must be plugged with higher taxes.

I, of course, start from the opposite direction – what is the optimal amount of tax to raise and what are the priorities for spending that money on?

- We are well above the optimal tax rates for a healthy economy and I would argue that we are very close to the highest amounts of tax (as a proportion of GDP) that the UK has ever managed to raise.

- Higher taxes will lead to avoidance which is likely to harm the economy.

On the spending side, foreign aid could be abolished, but would supply only £14 bn of the £80 bn pa they say that we need.

- I think that radical reform of the NHS is required (including charges) but that is an argument for another day.

On to the newspaper’s proposals, with the scene-setter that I only really support two kinds of tax:

- on income (when you get the money)

- on transactions (VAT – when you spend the money)

Thus IHT is double taxation and should be replaced by income tax on the recipient.

Annual levies on assets you hold (usually called “wealth” to make taxing is sound morally just) provide a perverse incentive to switch to assets that are less heavily taxed.

- They represent structural intervention in asset allocation decisions which mean that capital is not allocated efficiently.

And they make as much moral sense as taxing young people for the years of earnings potential that they have in front of them.

- Wealth largely represents successful decision making on the part of the wealthy, and taxing it provided is disincentive to make good decisions.

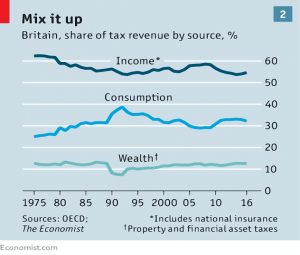

The Economist notes the UK’s starting position relative to the OECD:

- low income taxes, but with an averagely redistributive impact

- average consumption taxes

- highest wealth taxes in the OECD

It then looks at six specific proposals:

- higher income and corporation taxes (as proposed by Labour)

- these would impact efficiency, as rich people work less and pay more into their pensions, or even leave the country

- lowering the personal allowance

- I’m completely against this – I think it should be raised to the point where a minimum wage job incurs no income tax

- the newspaper agrees that higher income taxes reduce the incentive to work

- higher consumption and “sin” taxes (eg. on sugar and pollution)

- these are good, but wouldn’t raise enough money

- VAT loopholes – largely designed to make “essentials” affordable to the poor – could be closed

- But extending or increasing VAT would be regressive (impact the poor most)

- Which means another step down the slippery slope of increasing benefits to compensate

- Council tax re-rating with more bands

- This wouldn’t have the impact that most people expect – Councils levy tax to match their spending, and this would drive a “postcode lottery”

- People with the most expensive houses still wouldn’t pay the most, except at a local level

- My council tax (on a pricey house in London) is already a very great deal of money for what amounts to a weekly bin collection.

- Land value tax

- Lefties like this because owning land is hard to hide, and rich people tend to own a lot more

- But Labour’s garden tax was about a popular as the Tories’ dementia tax in the last election

- I’m against it because it’s essentially a tax on the successful parts of the country (London and the South East)

- And it would shift asset allocation once more, making renting more attractive than buying

- It might even trigger a property price collapse, with terrifying implications for the UK economy

- Lefties like this because owning land is hard to hide, and rich people tend to own a lot more

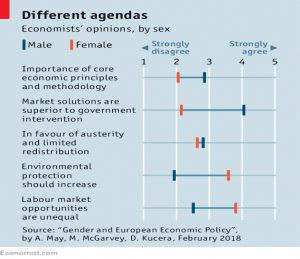

Female economists

Another article in the Economist contained the stunning revelation that male and female economists don’t think alike.

Men think core principles and methodology are more important.

- They also prefer market solutions to government intervention.

- They don’t support more environmental protection.

- And they don’t believe that the labour market is unfair.

No surprises there, then.

Advisors are bad

Being of a cynical nature, I have always assumed that financial advisors put their clients into bad investments because of a conflict of interests:

- They make money whether you do or not.

But a new paper suggests that most advisors invest personally in just the same way that they advise their clients.

- Which means that they trade frequently, chase returns, prefer expensive, actively managed funds, and under-diversify.

They have net returns of -3% pa, just like their clients.

By studying what advisors do after they leave the industry, the report’s authors were able to demonstrate that their expensive, under-performing portfolios were not held to persuade clients to do the same.

- Advisors continued to hold these portfolios even after they had become ex-advisors.

I am happy to see my cynicism proved wrong, but the outcome for the clients remains the same.

- I continue to suggest that you should become a DIY investor.

Twitter pics

After last week’s feast, a relative famine – I have just four for you.

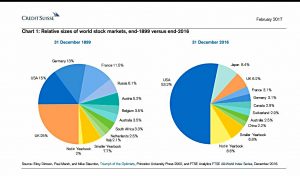

The first one shows the relative sizes of national stock markets at the end of 1899 and then again from the end of 2016.

- The UK’s share of the stock market is a quarter of what it was.

- During the same period, the US’s share has more than tripled.

Who would bet on the US retaining its current massive lead for another century?

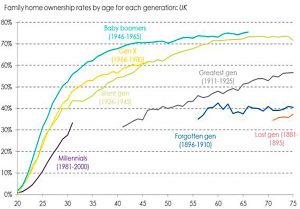

The remaining three are about property.

- The first shows home ownership by generation.

- It’s starting to look like the high ownership amongst the boomers is the aberration.

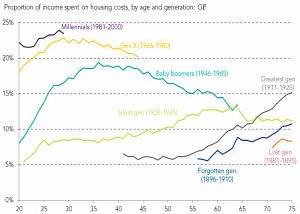

The next one shows the proportion of income spent on housing costs by each generation.

- I think this is more to do with lower salaries and higher rental costs.

- As we saw last week, low interest rates are keeping ownership costs relatively low for those who can afford to borrow enough money.

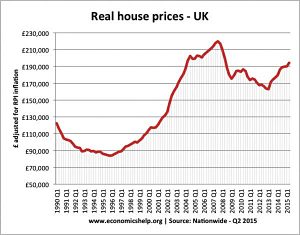

The final chart shows real house prices (unfortunately the series ends in 2015).

I have two comments:

- I really did choose the best time to trade up (1995).

- House price increases occur under Labour governments rather than Tory ones.

Until next time.