Weekly Roundup, 20th January 2015

As usual, we begin our weekly roundup in the FT.

Contents

FX Turbulence

Paul Murphy and Judith Evans ((along with Phillip Stafford, Michael Mackenzie and Alice Ross)) both wrote about the fallout from the sudden removal of the three-year-old Swiss Franc peg to the Euro by the Swiss National Bank. This led to a rapid double-digit appreciation of the Franc. Lots of retail FX trader accounts were wiped out and as the debts passed to their brokers, one of the platforms – Alpari – went under.

It’s hard not to feel sorry for the guys who may have lost a significant portion of their life savings, but for the rest of us it’s a valuable triple lesson in risk management:

- don’t trade FX via CFDs or spread-betting with a significant portion of your portfolio ((many would say that any retail FX trading is stupid))

- remember that leverage cuts both ways

(you win fast and you lose just as quickly) - and always use more than one broker

Retail FX now accounts for 20% of the market, with more than 4 million traders worldwide. In all probability, the UK client money segregation rules brought in after the 2008 crash will mean that the small traders have only lost the money implied by their Swiss Franc trades, not their entire accounts. But given the levels of leverage involved (from 5 times to 500 times – there are no caps in the UK) this may amount to the same thing.

The lack of a leverage cap was Paul Murphy’s main focus. In 2009, the flotation prospectus of Gain Capital revealed leverage of 200 to 1, and also made it clear that their retail “clients” were in fact counterparties – Gain was taking the other side of the trade. Increased leverage just reduced the time it took the clients to go bust, and so inflated Gain’s profits.

US regulators increased the capital needed by brokers, and capped leverage at 50 to 1. As predicted, the trade largely moved to London where there were no caps.

John Authers looked at the wider ramifications of the peg’s removal. One immediate impact will be to Eastern European mortgages: in countries like Hungary and Poland, lots of people take out loans in Swiss Francs to benefit from the low interest rates. ((those with very long memories may recall similar arrangements in the UK during the late 1980s and early 1990s)) It sounds like a good idea, but now those debts are suddenly 20 per cent larger.

The removal of a market distortion is in general A Good Thing, but with all sudden moves, the real risk is unknown at first – did any significant institutions have major exposure? Once the first domino falls, it’s difficult to predict how the game ends.

The euro is now at its lowest trade-weighted value for more than a decade, increasing its competitiveness against the US. This should be good for European stocks (even in Switzerland, where 10-year bond yields are almost zero). John also predicts gains for the dollar, US bonds and gold.

The bad news is that Switzerland faces a recession. But with ECB QE looming this week, the SNB would struggle to buy enough euros to maintain the peg. The SNB balance sheet is already up 300% from 2008, more than even the Banks of Japan.

At 86% of GDP, this may represent the high-water mark of central bank balance sheets. Like everyone else, the SNB is now cutting interest rates (to minus 0.75%) rather than trying to control exchange rates. The Fed is only at 25% of GDP, so it still has plenty of room to bail out the markets should it need to.

Deflation

Merryn correctly warned on deflation, which has been gettting a good press recently. UK inflation hit 0.5% in December, and those who drive ((most people, but not me)) seem very fixated on petrol prices. Even gas and electricity prices are beginning to fall. The word “joyflation” has been used. The problem is that the economy is designed for 2% inflation.

The biggest driver is borrowing. When I got on to the housing ladder in the 1980s inflation was over 5% and mortgage rates were around 12%. You paid through the nose for a few years, but eventually inflation reduced the payments. Meanwhile, the house went up in value, rapidly dwarfing the loan. I borrowed as much as possible for both of the houses I bought. ((in turn – I sold the first to fund the second))

Try that again with deflation: the cost of the loan grows relative to falling asset prices, and stays the same proportion of your static wage. Probably best to borrow a little less in that case.

The low interest rates of recent years mean that the cost of borrowing has been low, and instead of deleveraging, the UK has been adding debt. Deflation would mean that even these low interest rates would be above (negative) inflation, and people would finally have an incentive to repay debt.

The same goes for firms, who would have less money for investment. Less investment and less consumer spending means a recession and further deflation. So it’s not a good road to go down.

Merryn is not too worried – it’s only CPI that’s down to 0.5%. RPI is 1.6% and “core” inflation (which removes the volatility from food and energy) is 1.3%. Service sector inflation is 1.4%. I’m a little more worried myself. I never expected six years of financial repression with no end in sight, but a deflationary spiral could make this seem like the good old days.

Buy-to-let: pensions and the housing crisis

Jonthan Eley’s column was about the risk of pensioners “exploiting” the new freedoms from April to invest in buy-to-let. While this has obviously been a successful business over the last fifteen years, I’m not convinced that those prudent enough to build up large SIPPs (the median pension pot is 26K) will take the tax-hit for a punt on property.

Jonathan points out that 80% of people don’t know what a marginal tax rate is, and only 50% know how to save tax on pensions. I remain confident that the 20% who do understand tax are the ones with the big SIPPs.

He also runs through the other reasons not to do this:

- interest rates will rise in the end, certainly within the duration of a buy-to-let loan

- adding to your property exposure (assuming you own you own home) is the opposite of diversification

- house prices may fall – they have rarely been more expensive that they are now

- property is not liquid – it is time-consuming and expensive to sell

- political risk: a non-Tory coalition in May could well withdraw interest offsetting against property profits, or otherwise interfere; we might even build more homes

All good reasons, but honestly, you had me at “tax-hit”.

Still on housing, and still in the FT, the novelist Will Self wrote an opinion piece on the housing “crisis”.

Home ownership is at a 25-year low – 65% versus 70% in 2003. Self traces this back to the Thatcher government’s right-to-buy (at a discount) scheme. Intended to increase home ownership (which it did, at least at the start), Self argues that these ex-council properties have been flipped to a rentier class.

I can’t claim to keep close watch on what happens to ex-council properties, but in my area (I live a couple of miles south of Self) most of the change over the past twenty years has been the building of new private blocks on whatever brownfield land could be found.

The typical suburban plots for builder’s yards, strip malls and pentecostal churches have been replaced with two-bedders for twenty-something yuppies. The property crisis in my area is a shortage of small family homes for those who want children. I don’t think these people want to move onto ex-council estates.

Self goes on to say that “the prosperity of [the] rentier class has been achieved … at the direct cost of the least well-off.” This is baffling to me – the least well off are claiming housing benefit as they always were.

The increased bill from private rents over social rents is footed by the taxpayers, which is largely the middle class. Even the displaced lower social rents are misleading – the savings on housing benefit are matched by the lost rent below market rates that the public purse could have received.

Later on Self describes his son’s landlord as “a childhood friend who … won out early in the inheritance lottery.” I wonder if the landlord would describe losing a relative in that way. Much as I welcome contrasting views of economic issues, I hope this guest column isn’t the start of a new trend at the FT.

Self is right about one thing: with 64% of British bank loans being secured against residential property, any collapse in house prices would destabilise our banks once more.

Grexit

The Economist looked at the potential impact of Grexit:

- the drachma would fall by 50% against the euro

- inflation in Greece would reach 35%

- the Greek economy would contract by 8%

- pre-existing Greek debt in euros would grow so large as to be unpayable, leading to default and legal battles ((the recently-reissued bonds are covered by English law))

- Eurozone GDP would fall by 1.5% over 18 months

- there would be a sell-off of Italian and Spanish bonds

Not a pretty picture, but one we may have to face, given the opinion polls in Greece.

Beware heavily-traded stocks

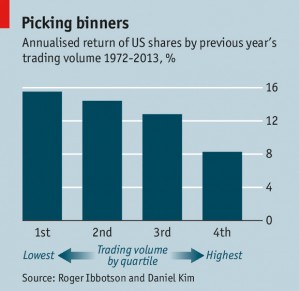

The Economist also reported on a study by Ibbotson and Idzorek which shows that “popular” (heavily-traded compared to their market value) stocks do not perform well.

Over the short-term (months) the opposite is true – popular stocks benefit from the momentum effect and outperform, until they reach valuations from which they must underperform. The long-term advantage of the least-traded stocks over the most-traded was 7% a year (US market).

As a control measure, the study also looked at beta. According to CAPM theory, high-beta (“high-risk”) stocks should out-perform, but GMO explained in 2011 that actually, low-beta stocks do better in the long-run. Ibbotson and Idzorek found that trading volume was more important than beta, as well as company size and starting valuation.

The small company effect and the value effect are usually explained in terms of risk compensation (ie. they are compatible with CAPM). But momentum and recent trading-volume (“popularity”) do not support CAPM – the information should already be in the price.

From a psychological (behavioural) perspective, momentum is easy to explain: demand for financial assets increases with price. Why people (including top fund managers) fail to notice that the price has risen too far, and continue to hold the stocks for too long, needs more thought. What we can say is that timing is everything.

Sweden’s AP7 fund

Finally, I am grateful to Meb Faber ((founder of Cambria funds, who I follow on Twitter)) for a tweet about the AP7 Safa fund in Sweden.

This is a government pension fund with a 1.5 leverage world equity / bond mix which lifestyles into bonds as you age. Annual fees start at 0.12% (age 55) and decline with the lifestyling down to 0.07% at age 75.

I think we could do with one of those in the UK. Is anyone in government listening?

Until next time.

1 Response

[…] Faber, who we’ve met before, has a new book out, his fourth. It’s called Global Asset Allocation, and it does what it […]