Weekly Roundup, 26th April 2016

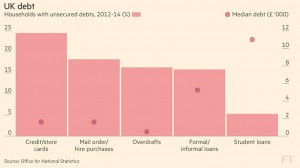

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week’s topic was unsecured household debt.

Contents

UK debt

Adam Palin looked at the non-mortgage and car debt held by UK households (using averages from 2012 to 2014.).

- Credit card debt was most common (25% of households)

- Next was mail order / hire purchase (18%)

- Then came overdrafts (16%)

- Then “other” loans (15%)

- And finally student loans (5%)

The median amounts owed under each category were also interesting:

- Here student loans are top, at £11K per household affected

- Other loans were at £5K

- Credit cards and mail order were each less than £2K

- And overdrafts averaged a few hundred pounds

Adding all this up for the country, “other” loans was the biggest pot, followed by student loans.

- 48% of households and 35% of individuals had some form of non-mortgage debt,

- with an average of £3.4K of debt across the individuals affected.

This is much less than the average £85K of mortgage debt amongst the 36% of people with a mortgage.

The debt is spread across income groups, with 42% of the lowest-earning fifth and 48% of the highest earning fifth having some unsecured debt.

- Debts rise in line with income (13% and 12% of income respectively – 15% for the middle fifth).

Wealth (net worth) on the other hand, is correlated with debt – 58% of the poorest fifth and 36% of the richest fifth have unsecured debt.

- That the gap is so small staggers me – why would anyone in the richest fifth of the country have unsecured (expensive) debt?

Other things that correlated with debt include children (two-thirds of parents have debt), age (only one in six of the over-60s has debt) and education (graduates are more than twice as likely to owe money).

- Again, not too surprising – parents have the largest outgoings, the over 60s have converted most of their human capital into real capital, and graduates often have student loans to repay.

Income Funds

Aime Williams looked at the problems facing UK income funds.

After a run of dividend cuts (Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, Rolls-Royce), and a general decrease in dividend cover in the FTSE stocks, the industry is debating what the term “income fund” should mean.

- This is a big deal because income funds are the darlings of UK retail investors.

- That’s why Neil Woodford is such a big cheese.

At the moment, a UK income fund has to have 80% of its assets invested in UK equities and it must yield 10% more than the FTSE All-Share index (measured over a trailing 3-year period).

- The FTSE-All Share’s current yield is 3.7%.

This is getting harder to do – 17 funds with £19bn of assets have been ejected over the last three years.

- Even Woodford’s flagship fund has come close.

So – surprise, surprise – the trade body the Investment Association ((The same bunch who squeezed out their chairman when he suggested they should be more transparent on fees )) is thinking about cutting the yield target, or getting rid of it altogether.

Obviously, I’m just a consumer, but I can’t see the point of an income sector if it doesn’t provide a higher income than the market.

- Ten per cent outperformance was a modest target to begin with.

- I think an absolute target (say 3% to 3.5% pa) should be used, otherwise we’re not talking about an income product.

But as a minimum, beat the market, guys.

- That’s what we pay you for.

Sitting on cash

Aime’s second article was about investor inertia.

- Apparently lots of savers are not investing their cash.

Boring Money has reported on a YouGov survey.

- Forty per cent of those with between £100K and £150K saved had no plans to invest.

- Cash ISAs remain far more popular than stocks, despite their poor long-term prospects.

There are three issues:

- stock market turbulence (’twas ever thus)

- confusion about how to invest

- unwillingness to pay for financial advice

The point about advice is the least surprising.

- It’s just not cost-effective at this size of portfolio.

- 25% of advisers have retired / quit since 2010 because of the RDR.

Only 8% of those surveyed were prepared to pay the £100 per hour needed, and only 22% of those with more than £150K.

Will robo-advice come to the rescue?

- 40% of those surveyed (in the £100K to £150K bracket) were interested in robo-advice.

I’m not convinced.

- The robot-services (eg. Nutmeg) remain significantly more expensive than the DIY route.

But perhaps these guys won’t notice.

Helicopter money

The Economist looked at the prospects for helicopter money.

Originally conceived by Milton Friedman in 1969 as free banknotes dropped from the sky, it was picked up – only half-seriously – by Ben Bernanke in the early 2000s as a possible answer to Japan’s persistent deflation.

They’re not laughing now.

- Japan still has problems, and so does the rest of the world.

- The ECB is thinking about it, and so is Japan.

- QE (printing money to buy government bonds) and low interest rates don’t seem to be working.

The practical implementation is more likely to involve time-limited vouchers that have to be spent on certain goods and services (perhaps those made locally).

- Government spending and / or tax cuts are weaker alternatives.

Helicopter money has advantages.

- Because there’s no increase in government debt to fund it, people don’t think that taxes will rise in the future to pay for it.

- Plus the vouchers can be time-limited.

For the areas that need it most, there are political problems – the ECB doesn’t have permission from EuroZone governments at the moment.

- And governments remain committed to reducing deficits and debt, despite being able to borrow at close to zero for 30 years.

It’s hard to see Germany risking a second bout of hyper-inflation, but the mechanics for helicopter money should be put in place.

- Even if they don’t operate the lever this year, when the next crisis strikes, it might be the only one left to pull.

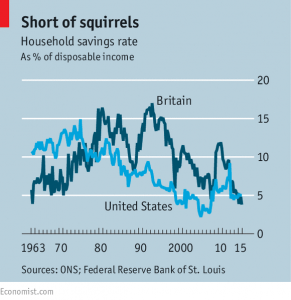

Household savings

Buttonwood looked at savings rates.

Negative interest rates don’t make sense to ordinary people.

- You should be rewarded for saving, and it should cost you to borrow money.

- Worse, because savings produce less return, people might save more, which is the opposite of what low and negative interest rates are supposed to produce.

Low interest rates also lead to corporate pension fund deficits.

Some economists put the causality the other way around – a “savings glut” means that the returns on investing must fall.

The problem with this theory is that the savings are in the wrong place.

- Old people in rich countries – especially those where DC pensions have replaced the more generous DB version – should be saving, but they aren’t.

The UK’s household-savings rate peaked at 16.2% in 1992. The average since 1963 is 10%. In 4Q2015 it was 3.8%.

- The US rate is 5.4%, again down from generally more than 10% between 1963 and 1985.

Household saving is supposed to be used by companies as investment.

- But they aren’t investing, despite being able to borrow (via corporate bonds) at 3%.

So with companies saving and households saving a bit, either the government must run a deficit or the excess must be exported.

- Germany exports, but the UK and US run deficits.

And around the corner are big financial challenges:

- the US owes 75% of GDP for Social Security (old age pensions), 18% for Medicare, 20% in federal pensions and another 20% for state pensions

- the UK owes 66% of GDP in government pensions

To fix that, taxes must be raised or benefits cut.

- Which brings us back to the idea that individuals need to save more for themselves.

They don’t seem to have realised, perhaps because the government is worried about the impact on consumer demand.

- The Economist recalls St Augustine: “Lord, make me chaste – but not yet.”

Executive pay

Schumpeter looked at executive pay.

A couple of weeks ago BP shareholders rejected a pay rise for Bob Dudley, on the back of the firm’s biggest ever operating loss.

- Of course the vote was only advisory – he’s already got the money.

- Smith & Nephew also lost a vote, based on awarding bonuses even though targets weren’t met.

- Anglo-American, VW and Citigroup face similar votes.

These revolts are unusual – only 1% of S&P 500, and 1 firm from the FTSE-100 lost votes last year.

It’s probably the financial crisis of 2008 that highlighted that managers could be paid millions, even as their firms crashed.

- Since then firms have tried to link rewards more to performance.

Which is not to say that rewards aren’t still enormous – Google’s CEO has a $200M deal.

The difference between Alphabet and the oil and mining companies is recent performance.

- When shareholders get burnt, they want to see the management suffer too.

The problem is that the policies that have been set are too complicated – hence Dudley’s reward even as the losses piled up and the share price crashed.

- The latest stupid idea is linking bonuses to diversity targets.

- How easy would that be to rig, without adding value to the firm?

Peer comparisons are useful, but they also need to be paired with absolute targets.

- Being the least bad oil firm isn’t good enough.

The Economist plumped for fixed salaries and hard-to-sell stock, linking rewards to long-term performance. I agree.

- Unlike many, I think that incentives are a good thing.

- But they need to be aligned with the interests of shareholders.

Oh, and cut the basic pay by a factor of ten.

- If you’re an entrepreneur, hang on to your stock and get paid in dividends.

- If you’re a hired manager, you don’t deserve millions whether you succeed or fail.

It’s not football.

Outsider CEOs

The newspaper also looked at the trend towards hiring CEOs from outside the company.

- It’s still uncommon of course, outsiders went from 14% of planned successions between 2004 and 2007 to 22% from 2012-15.

- Unplanned successions – when the current CEO is sacked – often involve outsiders.

Technology and regulation are key drivers.

- Outsiders make up 38% of incoming CEOs in telecoms, 32% in utilities, 29% in health care, 28% in energy and 26% in financial services.

- Finance firms hire from other finance firms, utilities hire from everywhere.

And boards are more independent, with CEOs and Chairmen less likely to force through an heir.

- Activist investors are a factor here, also.

One problem with going for outsiders is that it forces up pay (see previous section).

Insiders also last longer on average (5.8 years vs 4.8).

- But this is partly due to the number of outsiders brought into fix a broken firm.

- The new crop of outsiders hired during good times may fare better.

Brexit briefing

The Economist’s Brexit briefing began with George Osborne’s claim that leaving would reduce GDP by 6.2%.

- I find this hard to believe myself.

Osborne’s second point was that the EuroZone (EZ) would discriminate against Britain if we left.

- This was part of the recent government renegotiation of terms with the EU.

The EZ has 19 countries, making it a “qualified majority” that doesn’t need approval from the nine non-EZ countries.

- in practice they find it hard to agree amongst themselves

Finance is the key area of disagreement:

- bankers bonuses were capped (by the EU, not EZ) without British agreement

- EZ countries keep trying to impose a transactions tax (which ironically, the UK already has)

The renegotiation achieves four things:

- the EU will retain multiple currencies

- the EZ will not damage the single market, and the non-EZ countries will not impede more EZ integration

- EZ decisions can be appealed to a full EU summit

- Britain can keep its own financial regulations

EU countries are jealous of London’s financial pre-eminence, and would like to undermine it.

- The question is whether the new concessions will protect it.

Meanwhile, Bagehot looked at the extent to which Brexit is a nationalist campaign.

He recounts a visit to a pro-Brexit meeting in Hampshire, ((In a village a few miles from where I once lived )) where the mood was very different from what mainstream media would have you believe.

- The key point was that even if they lose, the Brexiteers will keep fighting.

- Vive la resistance.

This was die-hard country, with a 1984-style dystopian vision of Britain’s EU membership.

- It’s not a vision I share in detail, but I agree about one thing.

The economic arguments are full of what ifs, and it’s unlikely that staying or leaving would make a significant (ie. noticeable) difference to Britain’s prosperity in the long-run – just as it’s hard to argue that membership has led to great riches.

What is clear is that if we stay in, we do what the EU tells us, and if we leave, we can do what we want.

- That’s the central argument for me.

I could imagine a future where we have common interests with Germany, Holland and Denmark, possibly France. At a push, add Italy and Spain.

- But the relentless march eastwards of the EU – with Britain as a far-flung Western outpost – is something very different.

We’re as central to the EU as we were to the Roman Empire two thousand years ago.

- And what did the Romans ever do for us?

Until next time.