Weekly Roundup, 27th May 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with Merryn’s column in the FT.

Contents

Bond crash – not this year

Merryn wrote about when the 30-year bull market in bonds might end. More than half the world’s government bonds now yield less than 1%, something that no-one would have imagined in the early 1980s.

Bonds look un-investible at the moment, but for the market to turn, Merryn says we need one of four things:

- markets to demand a greater return to lend to governments

- inflation to soar

- economies to do so well that governments worry about overheating

- central banks to change their policies

None of these look particularly likely at the moment. Masses of debt and unfavourable demographics work against the inflation / overheating scenarios.

The deflationary dangers of QE are now starting to be discussed:

- creating oversupply through investment in projects that would be non-viable in tougher times, as in the oil market

- reducing spending by those who depend on the (lower) returns on capital

But we remain some way from policy change.

The bond market looks ripe for a crash – poor value, lack of liquidity, concentrated portfolios – and it may well be a nasty one. But there’s no particular reason for it to happen this summer.

P2P cherry-picking

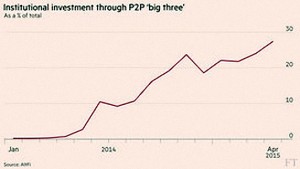

Judith Evans wrote about plans from the P2P lending trade body – the Peer-to-Peer Finance Association, or P2PFA – to introduce rules to prevent institutions “cherry-picking” the best loans at the expense of retail investors.

The institutional share of the market has grown rapidly over the past eighteen months, from almost zero at the start of 2104 to more than 25% now. Investment trusts have raised £500M to invest, and Metro Bank has a deal with Zopa. Landbay says that an unamed bank will be lending £250M pa through its platform.

In the US, the majority of loans are already made by institutions.

The main 3 platforms vary in their approach:

- Ratesetter has only the investment trust P2P investments on its books, with a 15% share

- Zopa uses randomisation to assign loans between institutional and individual pools, but has no institutional cap

- Funding Circle has a similar system to Zopa, but admits that loans turned down by institutions may be “recycled” into the retail pool

The current yield on P2P lending is 5.15%, according to the Liberum ALtFi Index.

Target date funds “failing”

Judith also reported on new research which shows that target date funds (also known in the UK as lifestyle funds) produce lower returns. These funds typically hold a lot of equities at first but move money into bonds to reduce risk as retirement approaches.

The Glidepath Illusion by Javier Estrada of Barcelona Business School looked at data from 19 countries over 110 years. He found that the switch to bonds reduced returns and made investors more likely to run out of money. The only “advantage” of the lifestyle funds was that they reduced volatility of returns, which is presumably how they are marketed.

Strategies which increased the allocations to equities towards retirement were more successful than the target date funds. A traditional 60/40 equity/bond split was also more successful than the life-styling approach.

This is not too surprising – bonds generally return less than equities. We seem to be stuck with an approach to retirement investing that is more appropriate to the days when retirement lasted only a few years.

Someone retiring today at 55 has a life expectancy – and hence an investment time horizon – of close to 30 years. Switching into bonds with 30 years to go can’t be right.

DB pension deficits

Josephine Cumbo reported that funding shortfalls in defined benefit pension schemes have increased, despite £44bn of extra contributions.

The aggregate deficit of the 6,000 private sector schemes covered by the Pension Protection fund was £375bn in January, up from £242bn three years earlier. It’s likely that bond market movements since January have significantly reduced the deficit.

The Pensions Regulator offered employers and trustees two options:

- take longer to eliminate the deficits

- change their assumptions about future investment returns

Although it sounds risky, I’m in favour of the second option.

Schemes are trapped into a valuation system that doesn’t work in the present climate of low interest rates. We need to increase equity allocations and calculate realistic average returns, so that the apparent deficit under the current system is reduced.

This is an issue that I will return to in a later post.

Hargreaves Lansdown

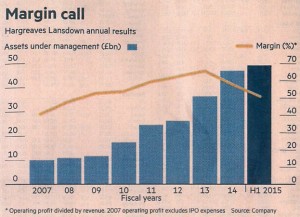

Lex took a quick look at the annual results from Hargreaves Lansdown (HL). The stock has performed very well since it floated in 2007, but is now on a PE of 35. Customer retention remains over 90% and the company has no debt.

Assets under management continue to rise (up 6.6%) but operating margins have come down since the FCA changed the rules on how fund management groups pay platforms (distributors) like HL. Lower interest rates on cash balances also impacted.

Looking for the oil dividend

John Authers wondered why consumers haven’t spent their oil dividend. Particularly in the US, the halving of the oil price in the second half of 2014 should have left more money in consumers’ pockets.

Last year the expectation was that this money would be spent, justifying the run-up in US stocks. This in turn should have produced an early interest rate rise from the Fed, and after that an increase in the dollar. Global developed stock markets show an increase in the price of consumer discretionary stocks in anticipation.

When none of this happened, these stocks fell back again, along with consumer confidence and corporate earnings. And now the oil price has turned back upwards.

John believes that wages are the key, and that only when they rise in real terms (as they have finally begun to in the UK) will the money be spent, and interest rates start to rise.

Osborne’s July Budget

Another week brings another commentator with suggestions for the first Tory budget in almost 20 years. This week it’s Matthew Lynn in MoneyWeek. With the Liberals out of the equation, we can forget about the Mansion Tax and hope for more cuts than rises.

Matthew’s list is a little shorter than the one from Claer Barrett that we looked at last time:

- Inheritance tax: at the time of Ken Clarke’s previous Tory budget in 1996, the party was committed to abolishing inheritance tax and capital gains tax. Matthew wants to see a no-strings £1M threshold, or ideally £2M immediately -IHT shouldn’t be a tax on the 65% who own houses.

- I totally support this one and find it faintly ridiculous that wanting to pass on a house you bought yourself is seen as the preserve of the super-rich

- Cut the top rate of income tax: Matthew wants to see the 40% rate return

- Barring the return of a Labour government even to the left of Milliband, I don’t expect to fall into the top rate tax band again, so I have no dog in this fight.

- But the economic argument stacks up – when Labour put the rate up to 50%, the tax take went down.

- When the Tories cut it to 45% the tax take went up. So it’s worth giving 40% another shot.

- For me, raising the threshold at which the top rate is paid is more important. It’s £42.4K at the moment. £50K would be a start, but £60K probably makes more sense in London.

- Cut the size of the tax code, which has doubled since Clarke’s budget, and implement Clarke’s promise to re-write it plain English.

- It’s difficult to argue with this one, though I can’t see Osborne making it a priority. He’ll have some more juggling to do before the end of this parliament, and the confusing nature of the tax code probably works in his favour at this stage.

- Regional tax codes: This is an interesting one.

- I think it’s quite easy to see after the General Election that the UK is now at least four regions (Scotland, Northern Ireland, the North and the South), even if drawing some of the lines would be quite difficult

- It’s worth at least looking at treating these regions differently – Scotland and Northern Ireland are obviously in the vanguard here, but the “Northern Powerhouse” sounds like another step in this direction.

- Matthew has in mind quite a few more regions that me – he would also split off Wales and the South West, and would separate the Midlands from the North. So he has seven regions.

- I’d like to see us move slowly in this direction, but I think that Scotland should be the canary in the coal mine, so this is probably one for the next term of parliament.

Basic Income

The Economist took at look at Basic Income, which we tackled as part of our General Election coverage. ((It was a Green party policy)) Following a national petition, there will soon be a Swiss vote on a basic income of $2,700 per month.

This is a lot more than was originally suggested by Thomas Paine in 1797. His one-off $2,000 at age 21 was conceived as a share of the returns on the common property of humanity (land, natural resources, but now also technologies like the radio spectrum).

Basic income tends to be seen by the left as part of the social safety net, and a redistribution of wealth to fight inequality. The right tend to see it an efficient delivery mechanism for welfare that is difficult to cheat and does not discourage work (since it it not withdrawn if you get a job).

The existing personal tax allowance in the UK of £10.6K at 20% is a similar system, worth £2,120 to 92% of the population. Extending it to all would not be prohibitively expensive. But £2K is not enough to live on, and the £8K to £12K that is enough would be too expensive to provide.

The mid-point of that range (£10K) amounts to approximately £40% of the UK average wage. Tobin (of the famous financial transaction tax) showed that to provide this would mean raising taxes by 40%.

If we assume a minimum tax base of something like 25% to fund education, police and infrastructure, it would mean overall taxes of 65%. This is way higher than UK taxes have ever been, and the current consensus is in favour of taking them back below 40%. ((As an interesting side note, to use a basic income to eradicate what the left calls “relative poverty” – to get to where no one has less than 60% of the median income – would require overall taxes of 85%!))

The Swiss proposal would cost 30% of GDP and will no doubt be defeated.

As an alternative, a “participation income” has been suggested, which excludes the idle. But what happens to them instead?

Market volatility

Buttonwood looked at the state of the markets. After falling towards parity with the dollar, the euro reversed in April. Yields on German 10-yr bonds were similarly headed for zero but changed direction.

As John Authers described above, with US growth weakening and a Fed rate rise disappearing over the horizon, better euro zone economic data caused a dollar sell-off. And now there may be another change of direction, as the ECB announced more bond purchases.

Weak global economic data (on trade and employment) suggests the world economy may be running out of steam. But fund managers appear to believe that there’s just been a bad quarter. Short-term interest rates are at their lowest for 40 years, and there seems no alternative to buying shares.

With central banks buying government bonds and companies buying their shares, net security issues is zero. The flows into pensions and funds will therefore push up prices, and increase the likelihood of more volatility in the future.

Equity resource notes

Finally, the Economist looked at Equity Resource Notes (ERNs), a new instrument designed to make banks safer. Leverage was a big factor in the 2008 financial crisis. Lehman’s held only 3.3% equity in 2007.

Debt is cheaper than equity (since banks are usually bailed out when they fail), comes with tax breaks on interest paid, and multiplies the effect of profits in good times (it also multiplies the effect of losses in bad times). Debt also has no impact on the control of a company – it does not imply ownership.

Regulators have since insisted on more equity. Contingent convertible bonds (cocos) turn into equity when the bank is in trouble, and their use has grown rapidly.

The problem with cocos is that they convert when regulators announce that a bank is short of capital. Making this announcement can cause a run on the bank. It also gives the coco holders an immediate loss, as the bank’s shares fall. If this loss puts the bondholders in trouble, contagion is a real possibility.

Jeremy Bulow of Stanford and Paul Klemperer of Oxford think that ERNs will help. The trigger for the conversion of an ERN is the bank’s share price.

At say 25% of the initial share value, the bond (ERN) interest is paid as shares instead of cash. And the shares are issued at the 25% level, even if the market price is below this. This gives the bank an instant paper “profit”. Redemptions of the whole ERN issue, when due, would be handled in the same way.

Regulator intervention is removed, and investors would know in advance when the share price was near the trigger level. ERNs should prop up the share price, whereas cocos push it down.

ERNs also have an interesting effect in a recovery:

- any ERNs issued at the 25% price would have a conversion price of 6.25%, so with the share price between 6.25% and 25%, new bond (ERN) holders receive cash while old bond (ERN) holders get more shares

- this avoids the normal “debt overhang” problem where cash is diverted to pay off existing debts rather than fund new ones.

The real (and real world) problem for ERNs will be convincing investors that ERNs are better for them than conventional bonds, rather than just better for the banks that issue them.

Until next time.

1 Response

[…] reported last week that the Economist had worked out that basic income was too expensive to implement. In the Huffington Post last week, Scott Santens – a basic income advocate and […]