Weekly Roundup, 29th March 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

All in it together

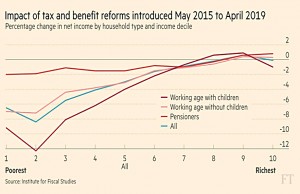

Adam Palin looked at the impact of this parliament’s changes to the UK tax and benefits regime on net household incomes.

- His article was based on a report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an “independent” think tank.

As you might expect, people at the bottom end of the income scale do worst, since the “austerity” measures have the most impact on those who take the most from the state.

- Those of working age with children do worst of all.

- Tax credits, housing benefit, income support and job seeker’s allowance are frozen, and the household welfare cap will come down from £26K to £23K (£20K outside London) next year.

- Child benefit will be restricted to two children (for new claimants) from 2017.

Pensioners do better because of the triple lock on pensions.

For richer people, increases to dividend tax and stamp duty are offset by increases in income tax allowances and capital gains cuts.

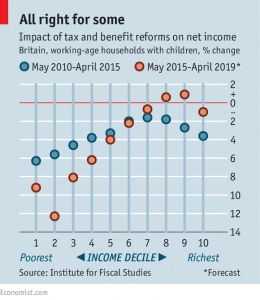

The Economist had a similar article with the same title.

- The Coalition reduced the deficit from 10% in 2010 to 5% in 2015.

- The current Tory government has pledged to eliminate the deficit by 2020.

The row after the latest budget was ostensibly about £1bn a year of “cuts” to the personal independence payment (PIP) to disabled people – in practice, spending was more likely to be flat than to come down.

Though the resignation of the work and pensions secretary was more likely about the Brexit referendum, his claim that the latest cuts are regressive is narrowly true.

- But this is almost unavoidable – the bottom fifth of working-age households receive 45% of their gross income as benefits, compared to the 2% that the top fifth received.

- If spending is to be cut – and to balance the budget it must, since raising more tax has historically proved impossible – it must be cut from those who it is spent on.

Disability, in general, is a reasonable area for regulation, but not because the allowances are massively generous.

- Believe it or not, there are more than 11 million people in the UK with a disability

- Half of these are of working age

- The number of claimants tripled under the previous Labour regime

- The annual bill is now £21 bn (up 369% under Labour)

- The “aids and appliances” funded by PIP now include things like beds and chairs which everyone needs.

Yet attempts to tighten up eligibility criteria have proved just as unpopular as “cuts”

- And bundling the changes with cuts to CGT, increased ISA limits and upgrades to personal allowances was never going to look good.

Looking at the tax and benefits changes to date, the newspaper concludes that because of a booming jobs market and cuts to banker bonuses, the impact on net incomes was relatively even across the board to 2015.

- But as we saw above, the impact over the next five years will not be even.

We are not all in it together anymore, but neither were we all in the queue when Labour was doling out more money than we had to spend.

Smart beta

John Authers wrote about smart beta, or passive factor investing.

- Beta is the return you get from passively investing in the market, whereas alpha is what you get from outsmarting the herd.

- Smart beta is a form of indexing, where rules that have worked in the past are used to create an alternative index that we hope will outperform in the future.

- This new index can then be tracked automatically at low-cost, as with traditional market cap indexes.

Smart beta funds often use “factor” strategies like value, momentum, dividends, sales, small companies, low volatility and equal weighting.

- None of these strategies will out-perform all of the time, but they should do well in the long run.

But as investors – and young investors in particular – switch from active to (cheaper) passive funds, smart beta is also a way for active manager to hang on to some of their revenue.

The investment industry has been pushing this approach for a few years now, but John says that the backlash has begun.

- John worries that once a market anomaly has been observed, it won’t continue.

- If people know that cheap stocks do well, they should buy them until the price is no longer cheap.

- It’s also possible that the factor was only identified through data mining or curve fitting.

I think this could be true for more esoteric factors, but the outperformance of value, momentum and small companies is based on timeless human emotions.

- Nevertheless, John quotes a study from Pete Hecht which shows that Nobel prize-winner Gene Fama’s factors worked much better before he published his paper.

It would be a mistake to believe the smart beta hype – whatever the investment industry is selling, you should be careful of buying.

- But if you believe in factors – and I believe in value, momentum and small companies, ((Low volatility is one I haven’t tried to apply myself to date)) then mixing together a few cheap smart beta funds to balance out volatility doesn’t strike me as a terrible approach.

Challenger banks

Aime Williams reported that fund managers are buying into the challenger banks – Metro, Shawbrook, Aldermore and Virgin Money – as the traditional banking model comes under pressure.

- Negative interest rates and the regulatory burden have pushed the bank sector down by 20% over the past year.

- Asset managers hope that the nimbler challengers will profit from lower lending by traditional banks, who need to rebuild their capital following the 2008 crash.

- Fidelity Investments, Pictet, BlackRock, and Kames Capital have increased their positions recently.

- JPMorgan Asset Management and Liontrust have held large positions since 2014 but have also increased their holdings.

At the moment, challenger banks have to hold more capital than large banks, but the BoE is thinking of changing this.

- Whether they can actually take market share is the real challenge.

Not free trade

Tim Harford looked at the economics of trade.

- The basic idea is that if Britain is good at software and France is good at making wine, we can swap some of our software for their wine.

- Jobs will be lost in the British wine industry, but gained in the British software industry.

- It’s a win-win because we end up with better wine, and the French end up with better software.

In this scenario, France acts as a “black box” for converting software into wine.

- Opposing free trade, by adding a tariff on the import of French wine would be the same as putting a tariff on the export of British software.

But what if the people who lost their jobs in the British wine industry couldn’t get jobs in the British software industry?

- Around 20 years ago, median household incomes were stagnating in the US and the UK, inequality was rising and manufacturing employment was falling.

- Was this global competition (free trade) or just technological disruption?

It looks as though for some industries, competition from China was the big factor.

In the US, Tennessee’s furniture industry was much more affected than Alabama’s heavy manufacturing.

- Those affected were affected more badly and for longer than economists expected.

- And export sectors have done less well than expected.

The US labour market seems to be the explanation – workers no longer change towns, industries and education level as easily as they did.

- Adjusting to change is likely to take a generation or two.

Which is too long for most people, and why many people in the current US presidential election (Trump, Sanders and their fans) oppose free trade.

Trade winds

The Economist’s weekly Brexit briefing was also coincidentally about trade.

- The pro-leave camp claims that Britain joined a trade area which has developed into a political union.

But what would happen to trade if we left?

The newspaper doubts that Britain would be able to negotiate good trade deals (to cover standards and regulations, as well as tariffs).

- Joining the EU has greatly boosted Britain’s exports there

- Though of course this means we are now a much more important supplier, and continued trade is more important for both parties.

The problem that up to now the EU has traded non-member access for an acceptance of most of the rules (including the free movement of people, and budget contributions – see Norway).

- Britain needs a better deal, and might not get it.

While Britain’s trade deficit gives the EU an incentive, the fear of other countries following a successful Britain through the exit door does the opposite.

- The deficit is misleading – we sell 45% of our exports to the EU, but they sell only 7% of their exports to us.

- And the new deal would need approval from 27 countries and the EU parliament.

Would the German car-makers have the clout to win it for Britain?

The fallback position is to use World Trade Organisation (WTO) deals, but these just remove certain tariffs and don’t apply to services.

- Financial services are a major British export to the EU, so there could be a significant impact to the City.

Britain may be too small for bilateral deals with individual countries (the EU has more than 50), but even if we aren’t we have no experience of negotiation during the past 40 years.

Digital advertising

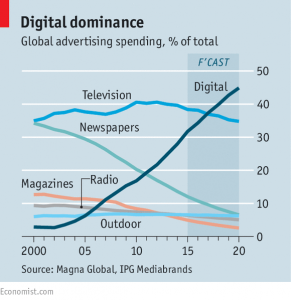

The Economist had a couple of articles about digital advertising.

- The first looked at fraud and the prospects for the industry.

It looks as though 2016 will be the year in which US online advertising finally outspends TV ads.

- Worldwide, this should happen in 2017.

Online ads are everywhere, and the advertisers know everything about you – and you in particular, not just the averages for your demographic.

- But the industry is a mess, with more than 2,500 companies involved.

This means that advertisers worry about whether their ad will be seen by real human eyes, or just robots trained to click to elicit payment.

- And lots of the humans are so sick of ads that they now use ad-blockers ((Please, if you are one of these people, white list this site ))

The industry is largely automated, with advertisers bidding for space on the web page as the human (profiled via cookies and tags) clicks in real-time.

- After an auction that lasts milliseconds, an ad is served.

In theory, the website gets the best price, and the advertiser gets the best exposure for what they were willing to pay.

- In practice, the trading of slots is full of middlemen analysing data and re-packaging both ads and slots.

- Sometimes 15 companies will be involved in the chain.

Other problems are technical:

- web-pages are bigger than the screens they are shown on,

- so how should you deal with an ad that isn’t seen,

- or is seen partially, or only for a brief time (during a jump or scroll)?

At the moment, half an ad viewable for one second – or two seconds of video – generally counts as a payable event (though some industry players set higher benchmarks).

- Of course, the same problems apply to TV and magazine ads, there’s just no data to analyse.

And then there is fraud – possibly $7 bn of it this year.

- There are plans to track who is getting paid for what so that any problems can be fixed as they are spotted.

And finally, there is blocking.

- For mobile users, in particular, ads slow things down and waste their data plans, so they’d rather just avoid them.

- Blocking will cost the industry $12 bn this year.

The most popular blocker is AdBlock Plus, which charges (or extorts, depending on who you listen to) to allow a few “nice ads” through.

Blocking is mostly on PCs at the moment, and the big question – discussed in the second article – is whether it will spread to smartphones.

- Ad blocking browsers for phones are already here, but lots of mobile users prefer apps, which still support ads.

More worryingly, operating systems – like that for Apple’s iPhones – and networks themselves (such as Three) can also block ads.

- This would still leave app users connecting via WiFi, which is the majority of them, as targets for ads.

- And ads are becoming “native” (in the style of other content) and encrypted, making them harder to block.

- And for legal reasons, network blocking will probably have to be opt-in.

The likely result of all these trends that the larger platforms (Google and Facebook) will come to dominate the industry.

- They already have more than half the mobile market, and this share is expected to grow.

US competition

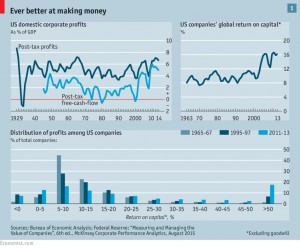

The Economist was also concerned about corporate profits in the US.

- Returns on equity for US firms are 40% higher in the US than abroad, which the newspaper puts down to a lack of competition.

- Domestic profits to GDP (one of Buffett’s favourite pricing measures) are near-record levels.

High profits could be down to innovations or investments, but they seem too persistent for this:

- A highly profitable firm now has an 80% chance of maintaining this situation for 10 years, up from 50% in the 1990s

And the firms generate too much cash – around $800 bn pa (4% of GDP) more than they spend.

- Much of this is trapped abroad by a punitive tax system.

The fact that outsize earnings aren’t competed away by new entrants suggests that there are competition issues, perhaps related to the massive corporate spending ($3bn pa) on government lobbyists and the growing importance of patent litigation.

- Microsoft is making double the profits it did in 2000 when charged under anti-trust regulation.

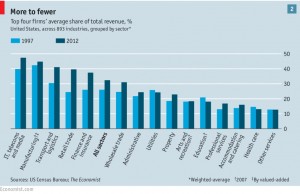

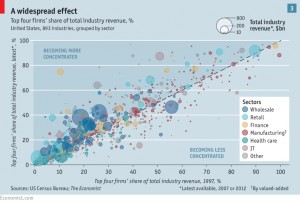

- Two thirds of industry sectors have become more concentrated since 1997.

The last time this happened – with the “nifty fifty” firms of the late 1960s – it came to a sudden natural end.

- Perhaps robotics and intelligent software will hasten the same conclusion.

Let’s hope so.

Until next time.