Weekly Roundup, 29th May 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Tim Harford. This week he was writing about waiting for problems to sort themselves.

Waiting

He begins with an anonymous donation of £500K in 1928 (£30M in today’s money).

- Stanley Baldwin (the PM) had asked for donations to clear the UK’s national debt.

£500K wasn’t enough, so it was put into trust, earning interest.

- It’s now worth £400M (still not enough by a long chalk) but the government has gone to court to get hold of the money.

Imagine how much it might be worth if it had been invested in a globally diversified multi-asset portfolio.

Tim imagines that the fund continues to grow at 3% more than the UK economy, whilst the debt stays in proportion to national income.

- I think both these assumptions are a stretch at the moment, but that doesn’t make in an interesting experiment.

The fund would double (relative to the debt) every 25 years.

- After 300 years (400 years after the bequest) it would be big enough to pay of the debt.

Tim moves on to the Kelly criterion – a 1956 formula for working out how much you should bet when you have a given edge.

- It’s a concept similar to withdrawal rates (SWRs) in decumulation.

- You need to make sure that your fund never drops to zero (so that you can’t bet again).

The real point is that in one sense it’s short-sighted of the government to use up the capital from the bequest now, rather than wait for it to pay off the debt.

- But that’s no different to all the governments that came before and decided not to run a surplus.

Governments reflect electorates (or should do) and almost everyone wants jam today.

- Thing get even harder when you want to account for the interests of future generations.

I have no children, and I struggle to look much further than my own death, and that of my other half.

Tightening or easing?

John Authers was trying to work out whether financial conditions are really tightening enough to make a difference.

- The Fed has been gradually raising rates – six times now – and making money more expensive.

But since oher countries are not tightening (Mark Carney signalled this week that there could be rate cuts post-Brexit), the impact is limited.

John points out that FX rates, stock market valuations and commodity prices (particularly oil) also affect general economic conditions.

- But the key rate is the real rate – the Fed rate minus inflation.

Looked at in the round, conditions have tightened in 2018:

- Nominal rates are up, the US stock market has paused and the dollar is stronger (this impacts US exporters and emerging market economies that have borrowed in dollars).

Most importantly, the real yield on 10-year Tips (US index-linked bonds) has doubled in six months, peaking at 0.93%.

- That’s the highest level since 2011.

It has since fallen back by 0.1%, forcing down yields on 10-year Treasuries from 3.1% to 2.9%.

John puts the turn down to new fed chairman Jay Powell saying that he won’t intervene to save stock markets by cutting rates.

- There will be no “Powell put”.

The Fed also published minutes showing that they consider a 2.2% inflation rate as acceptable as a 1.8% rate.

- Which means that future rate rises may take longer to arrive.

Added to that, problems in Italy, Turkey and North Korea make Treasuries a safe haven once more.

- Once again, John is waiting for a rise in inflation to trigger further tightening.

The big trend

Over in MoneyWeek, Bill Bonner was also talking about the 10-year Treasury yield hitting 3.1%:

The credit cycle has turned. Everything else is noise.

Bill believes in staying on the right side of what Richard Russell called “the primary trend”.

Of course, you can never be sure you’re on the right side of the primary trend, either. All you can do is watch the numbers and play the long game.

Russell entered the markets in the 1940s.

Stocks were low and bonds were high; it was time to take the other side of the trade. Rates bottomed out in 1949.

The 10-year yield then rose until the early 1980s, when it hit 16%.

- After that it declined until 2016, when it hit 1.4%.

Now Bill is convinced that the trend has turned again.

From under 1,000 in 1980, the Dow rose to over 26,000 in January 2018 – more than 25,000 Dow points over 38 years. Too bad … it looks like it is over.

Buying Treasuries

One of the deeper mysteries is why, in a falling market, there is still a buyer for every seller – J K Galbraith

The Economist looked at why people are still buying Treasuries, if Bill is right.

- Even people who believe that 3% is way too low for a long-term interest rate (I think it’s a little low, but 4% or 5% would be fine) might want government bonds.

For the Economist, these people are anyone with a “riskier” asset (stocks, property, corporate bonds) who wants to hedge against a recession.

- I think that the newspaper is confusing risk with price volatility here.

- With bond yields low and prices high, they are not risk-free, so I prefer to hedge by keeping more cash.

- But 3% yield (as a good starting point for an SWR in decumulation) is getting closer to the tipping point where bonds might seem attractive once more.

The Economist points out that Treasuries yield more than US stocks.

- But of course, they yield significantly less than UK stocks.

So for UK investors this argument doesn’t hold.

- If / when Gilts yield more than the FTSE-100, I will be tempted to buy them.

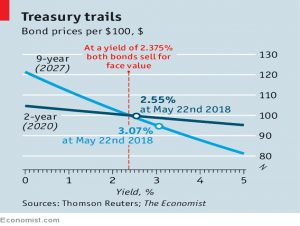

The more interesting part of the article looks at why people buy long bonds at 3% rather than two-year bonds at 2.6%.

- The reason is that in a recession, the long bonds would gain more.

That’s because the change in prevailing interest rates needs to be discounted over a longer period.

- In the chart above, the nine-year bond has a duration of 8, so a 1% change in interest produces an 8% change in price.

The idea is that in a recession, 10-yr yields might fall by 2%, producing a 17% gain.

- You could then sell your bonds and use the cash to buy stocks while they are cheap (I’m not sure how many would actually do this, though).

So whether you buy bonds depends on what you feel about the future.

- In a terrible crash, bonds will do better than stocks and property (each of which act as if they have a very long duration).

But they will still go down, and underperform cash.

- If you think that a 30-year period of rising rates has begun, you might want to wait for a better entry point.

Tax simplification

Josephine Cumbo reported on the latest missive from the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS).

- They want to “harmonise” the taxation of dividends to meet that of other income.

But of course, dividends are paid by companies after Corporation Tax has been paid.

- Whereas salaries and bonuses are paid before tax is deducted.

The proposal would make sense if at the same time, NIC rates were harmonised with Corporation Tax.

- But that might be too simple for the OTS.

Quick links

FT Adviser reported that the pension schemes of FTSE-100 companies have returned to surplus.

Cullen Roche explained why Buy Low, Sell High is so difficult.

Alpha Architect looked at a Bayesian approach to deciding what to do with underperforming assets.

That’s it for this week.

Until next time.