Weekly Roundup, 30th August 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with a survey of UK retail investing fees.

Contents

UK retail investing fees

Naomi Rovnick and Aime WIlliams looked at a study by Grant Thorton, which found that almost four years after the Retail Distribution Review (RDR), average annual fees for retail investors have only fallen from 2.86% pa to 2.56% pa.

- The survey assumes a £100K portfolio with “integrated advisers” like St James Place and Hargreaves Lansdown.

The RDR banned financial advisers (IFAs) from taking commissions from financial product providers.

- Getting rid of commissions was a good idea, since it removed the incentive for IFAs to recommend the products with the largest fees, rather than the best products.

But this meant that advisers had to charge an hourly fee for advice.

- Which in turn made IFAs too expensive for all but those with the largest portfolios.

Smaller investors use stockbrokers and fund supermarkets, where instead of commission they pay a holding fee or platform charge, on top of the cost of their underlying investments.

- The cost of the underlying investments has come down, but this is largely because there is no need any longer to reclaim the commissions through higher fees.

The high fees are of particular concern because returns are generally much lower in a low-growth, low interest-rate economy.

- The typical return on a discretionary portfolio in 2015 was 2.3% (after deducting fees).

Is education worth it?

Tim Harford looked at education, and in particular the record number of UK university places.

- Education is obviously good for people, but it comes at a cost in terms of time spent being non-productive and money because of the debts amassed to pay for both lectures and living expenses.

Tim looked at a paper from the LSE which examined whether universities themselves could be a boost to the region they are part of (presumably by encouraging well-qualified and productive people to hang around them.

- Inventions and patents exploited by local firms would be another factor.

The basic finding was that doubling the number of universities in a region led to a 4% increase in GDP per person.

- So if the doubling can be achieved at a cost of less than 4% of GDP, it should be good value for money.

Of course this can only work up to a point, since there is a limit to how many university-educated people are needed, and can achieve above average productivity (and earnings).

Tim also wrote about Bryan Caplan’s new book – The Case Against Education. ((I can’t find an Amazon link for this at the moment ))

Caplan finds it odd that many students (arts students in particular) learn little of use in the workplace but still end up with better career prospects.

- He sees education as a signal that students are smart and diligent.

- Which implies that it would be more efficient to find a way of identifying such people without the time and expense of a non-vocational 3-yr training course.

I certainly think that we are sending too many people (> 50%) to university, and far too many are studying subjects that will help no-one.

- But the question also arises that if we allow university staff to be our gatekeepers of future talent, who will make sure they behave in society’s interests?

UK universities are left-wing echo chambers obsessed with safe spaces and identity politics.

- I doubt that their lecturers are the best people to identify the workforce needed by a post-Brexit Britain in order to compete on the global stage.

How volatility really works

In the Investors Chronicle ((Reprinted in the Saturday FT )), Chris Dillow looked at what volatility really means.

Equity volatility – usually judged by the Vix index, a measure of implied volatility on S&P 500 options – has fallen close to the lowest levels since 2006.

- Some have taken this to mean that the market sees a low probability of share prices falling dramatically.

- Contrarian-minded observers wonder whether this might not be a sign of complacency, and hence a counter indicator.

Chris says this is not the case.

- Low volatility means that investors disagree.

- Prices are stable because markets are liquid, and buyers and sellers can find each other without moving the price much.

High volatility is a sign of consensus.

- Prices fall a lot when most investors want to sell.

- And they rise a lot when most investors want to buy.

So low volatility indicates a quite a few – though not all – investors are nervous.

- It’s not a sign of complacency.

Chris also notes that low volatility lead more often to rising UK share prices than to falling ones.

- The correlation between the Vix and the FTSE All Share for the following month is negative, at -0.28.

- The dramatic falls of the dot-com bubble and the 2008 crisis were accompanied by high volatility rather than low.

4% inflation target

As the central bankers of the world gather for their annual meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the Economist has sided with John Williams of the San Francisco Fed, who thinks that a higher inflation target is needed.

- For close to 30 years, central bankers in western economies have targeted something close to 2% pa inflation.

- Emerging market economies often have a higher target (eg. 4% in India and Indonesia, 4.5% in Brazil).

When the policy was formulated in the 1990s, bankers expected inflation to be above target as much as it was below.

- And the “neutral / natural real rate of interest” (NRRI, or r* / r-star) which balances supply and demand for savings. was around 3.5%.

Inflation has now been low for years, and the natural rate of interest is below 1% (and possibly close to zero).

- This is probably because ageing demographics lead to more savings even though low growth forecasts have cut investment.

- This means that even base rates of 0.25% can mean relatively tight monetary policy.

Nominal interest rates (base rates) are just NRRI plus inflation, so they are unlikely to rise beyond 3%.

- This leaves little room for cuts to help reduce the impact of the next recession.

Note however that Janet Yellen implied last week that 3% would be more than enough leeway.

- The Economist points out that in the last three recessions, US cuts of 6.8%, 5,5% and 5.1% were needed.

Since inflation has been below target for so long, even a raise in the target to 4% might not be believed by consumers and investors.

- If they can’t generate 2% pa inflation, how would they generate 4% pa inflation?

The newspaper would prefer a switch to a GDP target.

- But is GDP a meaningful number, and does anyone apart from economists understand it?

My vote goes for an increase to a 4% inflation target (and some helicopter money).

Haldane puts his foot in it again

You may remember Andy Haldane – Chief Economist at the Bank of England – saying a few months ago that he couldn’t understand pensions.

- Well this week he’s quoted in the Sunday Times as saying that property is better for retirement planning than a pension.

- His argument is that we don’t build enough houses in the UK (true enough), so that house prices will continue to rise (quite possibly).

But that doesn’t mean that he’s right about pensions.

- There is no tax-relief on the way in to property.

- Tax relief on property gains is limited to your main residence.

- One property is plenty of exposure to that asset class for most investors.

- Property is now expensive to both buy and maintain.

- Equities have a better long-term track record than property.

- You can have a low-cost, fully diversified portfolio within a SIPP.

- Pension freedoms mean that you can now use flexible income drawdown rather than buy an expensive annuity.

- You can also withdraw 25% of the pot tax-free at age 55.

- And if you die before age 75, you can pass on your pension without paying inheritance tax.

Not to mention the fact that Haldane earns £200K pa and has a £3M defined benefit final salary pension to fall back on.

- As Tom McPhail from Hargreaves Lansdown said: “Perhaps we should take away his final salary pension and just give him another house instead”.

Mark Carney should have a word with him and tell Haldane to shut up about pensions.

The left behind

We’ve talked a lot about the effects of free trade in recent months, and how unfettered globalism can impact those whose jobs are globalised to a cheaper jurisdiction.

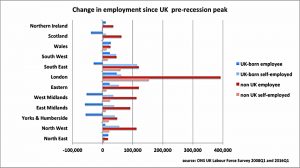

- I’m grateful to Flip Chart Fairy Tales (FCFT) for bringing to my attention two charts from Michael O’Connor and one from James Gleeson.

The first breaks down job growth by region into four categories:

- UK-born and non-UK

- employees and self-employed

Firstly, most of the growth is in London and the South East

- Second, the London growth is mostly of non-UK employees

- Third, growth outside London is mostly self-employed, particularly for the UK-born.

FCFT puts it down to the mobility of younger people without children, who are often not UK-born.

- They are more prepared to travel to where the jobs are (ie. from the rest of Europe to London and the South-East).

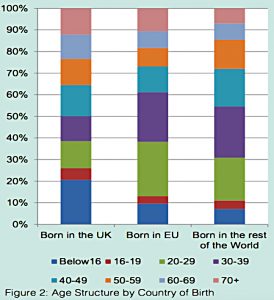

The second chart shows the varying age profiles of UK-born, EU and Rest of the World populations in the UK.

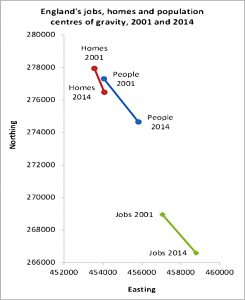

The third chart shows how the “centre of gravity” for jobs in the UK has moved south and a bit east over the past decade.

- Population has done the same, from a more north-westerly base.

- Houses lag even further behind.

The people left behind by the jobs shift have to set up their own businesses, however marginal they might be.

- All in all, support for both the Brexit vote and rising house prices in the South East.

The $1,500 sandwich

And finally, a look at the opposite extreme in terms of trade.

- Merryn wrote in MoneyWeek about a sandwich made from scratch – really from scratch – by Andy George in 2015.

He:

- made his own cheese

- harvested his own wheat

- collected honey

- made some bread

- killed a chicken himself

- evaporated sea water to get salt

- pickled a homegrown cucumber

- grew his own sunflower seeds for oil

It took him six months to make the sandwich and it cost around $1,500 – 300 times the cost of the average of the shop equivalent.

- A very good argument for the division of labour at least, if not quite for unfettered free trade.

Until next time.