Weekly Roundup, 7th December 2016

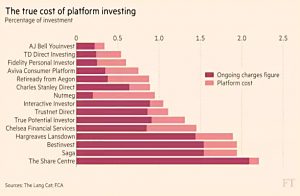

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about investment platform costs.

Contents

Investment platform costs

After the distractions of the Trump election and the Autumn Statement, there’s a lot to get through this week, so I won’t be hanging around.

In the first of three of her articles that we’ll look at this week, Aime Williams examined the costs of using various investment platforms, or rather, the cost of holding a ready-made investment portfolio on a platform.

- The data came from consultancy The Lang Cat, and from the FCA.

The chart below shows the cost of a “mid-risk” portfolio of £50K.

- There’s no mention of SIPPs or ISAs, so I’m assuming these are simple taxable accounts.

- That’s important, because these tend to be cheaper than sheltered accounts.

I’m also assuming that this is a buy and hold portfolio as there is no mention of dealing commissions.

- To be fair, this is a fund portfolio rather than an ETF / investment trust portfolio, so dealing costs are likely to be minimal in any case.

AJ Bell and Fidelity come out of this well, as does TD Direct.

- TD Direct didn’t do so well on our own recent comparison of costs, since its dealing charges are high at £12.95 per transaction.

Our cheapest broker (iWeb) is not listed by Lang Cat, presumably because they don’t offer ready-made portfolios.

- It’s also worth pointing out that market leader Hargreaves Lansdown is at the expensive end of the scale, charging more than 1.8% pa, or triple what the three winners cost.

I am generally skeptical of surveys like this one, since the underlying assumptions make the winners irrelevant to my needs.

- Here we have a taxable buy-and-hold portfolio of funds, whereas I need a tax-sheltered, semi-active portfolio of ETFs and investment trusts.

That said, the top three platforms come in at between 0.3% and 0.6% pa, which is competitive with a DIY portfolio.

- If you like funds, they are worth looking into.

VCT fund raising

Aime also noted that VCTs won’t be raising as much money as normal this year, even though demand is high.

- Baronsmead is one of the leading VC firms to have announced that they probably won’t raise more money.

- Northern is raising just £6M this year.

Fundraising has risen since 2005 and the firms still have plenty of cash left to invest.

- EU-driven rule-tightening also means that there are fewer qualifying companies to invest in.

- Management buyouts have been banned, and companies need to be unlisted, have assets of less than £15M and no more than 250 employees.

I’ll be looking at EIS-based alternatives to VCTs later this month.

Zopa

Aime’s third story was about Zopa.

The firm – which has 20% of the UK P2P market – has stopped accepting new money from retail lenders in the light of falling demand from borrowers.

- Zopa has also applied for a banking licence and is looking to offer deposit accounts.

There has been concern recently that institutions have been cherry-picking P2P loans – banks alone now account for a quarter of lending on UK P2P sites.

- Average returns have dropped from 5.4% pa in June to 5.1% today.

But some observers looked on the bright side, suggesting that the alternative would have been for Zopa to lower its credit standards to generate new demand for loans to match the demand for lending.

Non-cash pension contributions

Josephine Cumbo reported that HMRC is withholding tax rebates on non-cash contributions to pensions.

- “In specie” contributions (usually shares or commercial property) qualify for the same tax relief as cash, and are usually used by company directors whose cash is tied up in their small business.

Apparently HMRC is concerned that proper procedures are not being followed, and overvalued / hard-to-value intellectual property assets are started to be submitted as contributions.

- HMRC are said to be looking at all non-cash contributions since 2009.

Meanwhile most pension providers are no longer accepting non-cash contributions.

Robo-advice

Jason Butler argued that technology can’t replace human financial advisors.

He sees the major attraction of robo advisors as their cheapness:

- digital services average 1% pa, compared with 1.4% to 2.2% for traditional firms.

That may be the pitch to the venture capital firms the robo-advisors are trying to raise money from, but 1% pa just isn’t cheap enough.

- You can manage around 0.6% with a DIY approach, and the scale economies available to the robo-advisors should mean that charges are below 0.5%.

- Indeed, Jason himself uses Vanguard funds on the Alliance Trust platform, and reckons portfolios above £500K can be managed for 0.3% pa.

He also points out that robo-advisors have only one solution for every problem – an investment portfolio.

- A “real” advisor can also talk about debt reduction, building a cash reserve, and decumulation plans.

- They can also take into account your attitude to money and psychological biases like your risk tolerance.

This is true of course, but I think we’re getting into Financial Life Coaching at this point – or as they call it in the states, FinLife.

- We looked at this earlier this year.

- I think this could be the way that financial advice evolves, but most IFAs in the UK would fall short at the moment.

And those that could do all this would charge through the nose for it.

Jason thinks that rather than “painting by numbers” robo-advisors, we need to find a way to reduce the cost of FinLife.

- Technology (software tools, screen sharing and video conferencing) is part of this, but not the whole solution.

FinLife needs to be funded by a flat (affordable) annual fee.

- The trouble is, it’s not in an advisor’s interests to move in this direction, since they will make less money.

Of course, you don’t need an advisor to do any of these things for yourself – all of the necessary information is available on websites like this one.

- But Jason is right to point out that the robo-advisors are not suited to these FinLife tasks.

DIY investment manager

John Kay has published an updated edition of his book – The Long and the Short of It.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1781256756]

in the FT, he looked at how you can be your own investment manager.

There’s a “bias to activity” in financial advice – people don’t want to pay a lot of money to hear that they should do nothing.

- So you have the opportunity to do better.

John’s first recommendation is to “build a portfolio of index funds in line with the average asset allocation of major institutions”.

- This will save money but require some work.

Strangely, John recommends using the allocations from local authority pension funds.

- These were 60%-65% shares (with just over half in UK shares and the rest in international shares).

- The rest was made up of 15% to 20% bonds, 5% to 10% property, and around 10% in cash and other assets.

This is not a terrible allocation, but it comes from an unusual source.

- I would also argue that bond should be avoided for the next couple of years.

- You should do just as well in the long-run with any reasonable fixed asset allocation (provided there is diversification over geography and assets).

The emphasis on low costs comes from the idea that markets are efficient, and therefore unbeatable.

But of course markets are not always efficient, as evidenced by Warren Buffet.

- John draws our attention to short-term momentum, and longer-term reversion to the mean.

- He also poo-poohs the idea that risk is volatility – instead it’s personal, and related to your own portfolio’s chances of meeting your goals.

But he doesn’t believe that a David with “a home computer, a proprietary software packages and a book of trading rules” will outperform.

- Instead he recommends patience, and looking for undervalued assets (value investing).

- The only sources of value are “tangible assets and competitive advantage”.

Final salary pension transfers

Merryn was suggesting that it might be worth cashing in your final salary pension, since transfer values are at record highs.

- She points out that transfer values have risen by 480% over the last seven years (a compound growth rate of 25% pa).

- This is because their size is entirely dependent on the bond market (on interest rates).

Transfer values are now at 40 times the projected annual income, which is very good indeed.

- So you would only need to generate a 2.5% real return on the cashed-in value to come out ahead.

- And you would still have the capital to fall back on in retirement if things didn’t work out as planned.

So with the the 30-year bull market in bonds potentially coming to end, could now be a good time to sell?

- The answer is both yes and no.

It seems more than reasonable to assume that values won’t rise from here.

- But then you have to decide what to do with the money.

Nothing else looks particularly cheap at the moment, and once you’ve cashed in your defined benefits pension, you can’t buy it back again when market conditions change.

- DB pensions offer index-linked (almost) guaranteed regular income, which is expensive to replace.

I look at my own (small) DB pensions as diversification.

I have around 40% of my total net worth in equities, and around another 40% tied up in property.

- The 7% (present value equivalent) I have in DB pensions is a bond-like asset class that works well with the two big lumps of my portfolio.

So I’ll be hanging on for now, even though I fully expect transfer values to decline from here.

Bond markets

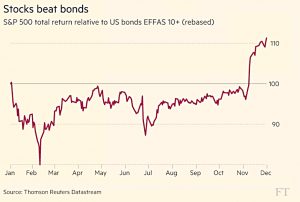

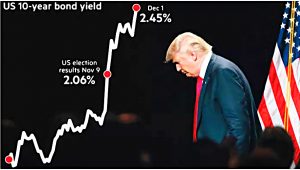

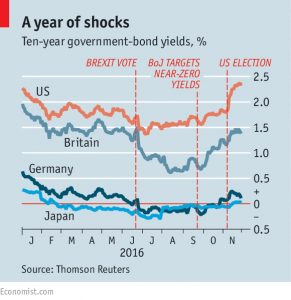

And so to the question of whether bond markets have turned, as yields begin to rise.

John Authers thinks not.

- And over in the Economist, Buttonwood was coming to a similar conclusion, largely because the yield rise has so far been confined to the US.

- The Economist feels that more populism – say the election of Marine Le Pen as French president – would be needed for the rise to spread.

John points out that rising bond yields (falling prices) do matter – they lead to a rise in interest rates, which is good news for savers and pension fund trustees, and not so good for those with mortgages.

- Higher yields also allow for more of a spread, which makes banks and insurance companies more profitable.

Higher bond yields in a particular country also draw foreign money to that country, and so its exchange rate hardens.

- Imports become cheaper and exports more difficult.

And of course, higher yields mean that bonds are cheaper (and more attractive) relative to stocks, which should draw money away from stocks, pushing down prices.

- Note however that if investors expect a long decline in bond prices, they may want to wait for a while.

The higher yields also mean that companies need to pay more to borrow, which should depress profits.

All of the above counts double for US bonds, since their yield is used as the global risk-free rate, and the dollar is used as the global reserve currency.

Having established that yields matter, John explains that they have risen because of inflation expectations.

- The US forecast is now for more than 2% inflation for the next 10 years – the highest for more than two years.

- The rising oil price is part of this.

- So is Trump’s likely fiscal expansion (tax cuts and infrastructure spending).

And the Fed will probably raise rates three times in the next year.

Against this, the down-trend from 1984 has not yet been broken.

- And the demographics of retiring baby boomers switching from stocks to bonds also supports prices (and holds down yields).

So John is waiting for the 10-year Treasury to yield 3% until he calls it.

- This last happened during the “taper tantrum” of 2013, when the Fed signalled that QE would slow.

Stronger dollar

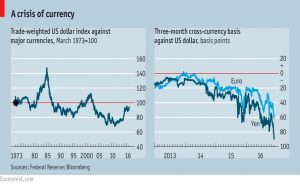

Now for the flip side of rising Treasury yields, the stronger dollar, as covered in the Economist.

- The dollar is now 40% above its lows of 2011 against developed countries.

- The Chinese yuan is at its lowest level against the dollar since 2008.

- India’s currency is at an all-time low.

The dollar is crucial to the world economy – some 60% of the world’s population (and 60% of its GDP) are in a de-facto dollar zone.

A rising dollar increases the cost of dollar denominated debts in emerging markets.

- This causes capital to flow out of EM countries, and their asset prices to fall.

- Countries like Brazil, Chile and Turkey are particularly vulnerable.

At home, the US trade deficit will widen (more cheap imports, fewer expensive exports).

- This in turn could lead to tariffs and protectionism.

Sell-side analysis

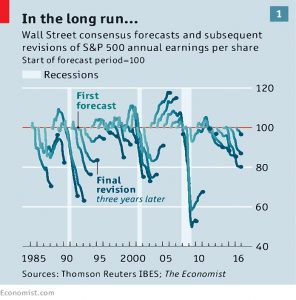

The Economist reported that sell-side investment analysis is reliably too bullish.

- 49% of S&P 500 firms are rated a buy, 45% are a hold and just 6% are a sell.

- Despite this, some 30% of these firms showed negative returns over the past year.

Profit forecasts are also too optimistic.

- Aggregate market earnings predictions made in the first half of the year have been revised downwards in 34 of the past 40 years.

Research suggests that analysts use three shortcuts to avoid the time consuming process of building their own discounted revenue and expenses models:

- they look at similar companies to make “reasonable” estimates

- they follow the herd, by echoing what their peers are saying

- they ask the companies what their earnings will be

To maintain good relations with companies, so that they are able to ask directly about earnings, analysts like to issue slightly negative short-term predictions.

- This means that companies can “beat” them when the official announcement is made.

- Since 2008, this has happened 70% of the time, with an average beat of 1.4%.

For forecasts greater than one year in the future, the best approach is to take the previous year’s earnings and compound by 107% (the average growth rate of the US market).

- This will be closer on average than analyst predictions.

The Economist used the historical downward correction to forecasts to build a model that improved further on this simple rule.

Short-term bias is harder to eliminate.

- You could just add 1.4% to the estimate.

- Or you could look at crowd-sourcing sites where people “guess” the results.

- Sites like Estimize beat Wall St estimates two-thirds of the time.

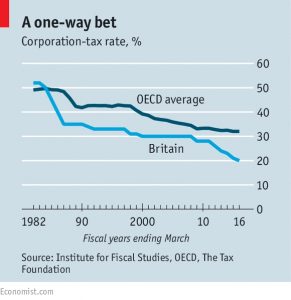

Corporation tax

The Economist also came out against Philip Hammond’s proposed cuts to corporation tax.

- He will bring it down to 17% by 2020, but Theresa May has been hinting that it will be the lowest in the G20, which means that it’s headed for 15% at least.

The idea is that post-Brexit Britain is “open for business”.

- But just 1% of firms pay 80% of the Corporation tax, so most firms won’t be encouraged.

- And it’s not clear that those who save will reinvest the savings towards future growth.

Funding long-term care

One of the topics missing from the Autumn Statement was long-term care costs.

- Care costs up to £1K per week, and the average stay for people who move into long-term care is between two and two and a half years.

- So there is a potential bill of £80K to £125K per person – with a slight possibility of much more than this – and no real way to insure against it.

A few years ago the government proposed that bills would be capped, initially at around £30K per person, and then after a review at something like £75K per person.

- As far as I know, this is still part of the Tory manifesto for this parliament, though things seem to have gone awfully quiet.

Over in Money Marketing, Paul Lewis from Radio 4’s MoneyBox was arguing that long-term care should be funded from people’s property assets.

- This is essentially the current system, so at first I wasn’t entirely sure what the point of Paul’s article was.

It turns out that Paul is upset that if one half of a couple goes into care, their shared home is ring-fenced so long as the other partner (or in fact, any relative over 60) is living there.

- Paul thinks this is unfair to “the taxpayer”, and a debt secured on the house should start to build up immediately.

- So Paul wants the prudent to pay for something that the profligate would get for free.

He believes that when asset prices rise over time, the gains weren’t “paid for” by the owners, and so don’t belong to them.

- Instead, the gains were “created by the way that society works … so there is an argument that that society has a right to its share of that windfall gain”.

Maybe in Cuba, Paul, but not over here.

- People who invest their money sensibly – and over the past 20 years in particular, that has meant at least a proportion of property – deserve their gains.

And when people die, they have the right to pass on those gains as they see fit.

- People who spend all their money as they go through life don’t deserve those gains.

Property rights – including the right to gains on that property – are basic to a civilised society, and we erode them at our peril.

Until next time.