Weekly Roundup, 9th June 2015

Today’s Weekly Roundup is mostly about bubbles, but we begin with our Chart of the Week.

Contents

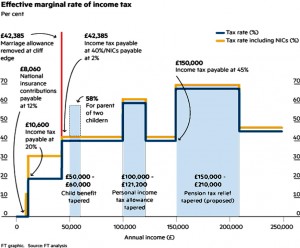

UK Tax system

Adam Palin wrote about the traps within the UK tax system. Much of the article was concerned with people on much higher incomes than we normally write about, but the complexity of the system is plain to see.

Adam identified four traps:

- personal allowance tapering from £100K to £120K

- pension contribution restrictions (proposed) on those above £150K

- child benefit tapering between £50K and £60K

- personal allowance transfers for married couples, removed above £42.4K

I agree that the system needs to be simplified, and the use of fiscal drag ((Where thresholds don’t keep up with inflation, dragging ever more people into higher-rate bands)) has to stop, but the priority for reform should be those on between £12K (the minimum wage) and £50K.

After that we can take a look at people with an income between £50K and £100K. £100K is more than enough for people to live a comfortable life and put something away towards tomorrow, even in London. It will be a long time before those on more than £100K are a priority.

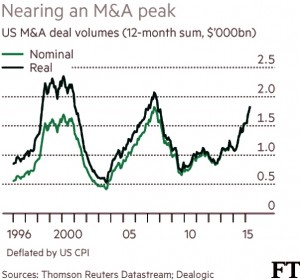

Is this the top for US stocks?

John Authers looked at whether this was the top for US stocks. M&A volumes have just exceeded the previous record, set in 2007 (though in real terms, activity is still below the 2000 and 2007 peaks).

April saw the record for share buybacks by US companies, again beating a record from just before the financial crisis. Buy-backs help to prop up share prices, but they also speak to a lack of opportunities to invest in future growth.

The market is also running out of steam – the S&P 500 is where it was at the start of the year.

A fourth factor is bond yields. In six weeks the 10-year Bund yield has gone from almost zero to 1%. The previous similar spike was in 1998 when Long Term Capital Management collapsed. Draghi, like Greenspan in 1998, told the markets to expect more volatility (ie. price falls).

The top will probably be marked by the Fed raising interest rates, which is why last week’s strong jobs report (which brings the date of the rate rise closer) was received badly. ((Rising interest rates and bond yields increase the rate used to discount stocks’ future earnings, which reduces their current value))

But John notes that the last two bond yield jumps (in 1998 and 2007) actually produced rate cuts from the Fed, prolonging stock rallies by a year in 2007 and more than 18 months in 1998.

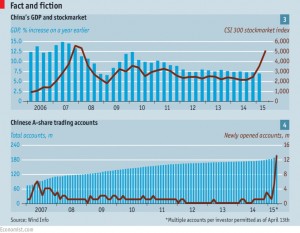

Bubble in China?

The Economist was worried about a stockmarket bubble in China. There are plenty of signs:

- The CSI300, an index of the biggest mainland stocks, has more than doubled over the past year. ChiNext (a market for startups) has tripled.

- Stocks listed in Shenzhen (mostly tech firms) have an average PE of 64; the small stock exchange has a for those on the exchange for small and medium-sized enterprises it is 80.

- Stocks listed in Hong Kong and Shanghai trade at a 30% premium on the mainland.

- In a single week in April, Chinese retail investors opened 4m new trading accounts.

- Many have bought shares using borrowed money. Margin financing has more than quintupled over the past year to 2 trillion yuan ($325 billion). Credit Suisse estimates that credit-financed purchases have reached 9% of market capitalisation, five times more than most developed markets.

But the correction will not be as dramatic as it would be in America or Europe. Free-float market capitalisation is about 40% of GDP, with the particularly frothy ChiNext at less than 10% of GDP.

Most developed markets are more than 100% of GDP. In China, households have allocated less than 10% of their wealth to shares.

The drop will also be slow, since mainland markets – unlike Hong Kong – have “circuit-breakers” that suspend trading on a 10% fall.

The bigger worry is that a crash would impact the development of China’s equity markets. After the last bust in 2007, share prices stagnated for seven years.

And China needs more equity investment: debt has increased from 150% of GDP in 2008 to 250% now.

A crash could also slow down financial liberalisation, which is needed to avoid more booms and busts:

- Making it easier to short stocks would allow for downward pressure on rocketing shares

- Giving mainland investors access to foreign stock exchanges would divert some of the cash from China

- Speeding up listing processes would improve the supply of equities so that new money wasnt forced to chase existing stocks

I see no bubbles

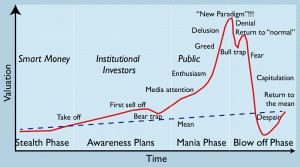

Over in MoneyWeek, David Stevenson wasn’t convinced by the bubble hype. David began by looking at the classic chart of a bubble, from Hofstra University New York.

There are four stages:

- the stealth phase, when the earliest investors buy in

- the awareness phase, when institutions arrive

- the mania phase (private investors), with the creation of arguments that explain why “it’s different this time”

- capitulation and sell-off

David worries that the diagram is misleading when it comes to fundamental shifts in economies and asset pricing, and tech in particular. He looked at four sectors where bubbles seem to be present.

Bonds – David believes we are halfway through a multi-decade cycle of extraordinarily low interest rates. Rates may go up to perhaps 2%, but they’ll come down quickly again as the global economy sputters.

In this environment, bonds look attractive as a long-term bet on lower growth.

Bund yields may have recently risen from zero to 1% (see above), but in July 2014 yields were 1.4%. For real capitulation, yields would be crashing back up towards the pre-2007 levels of around 5%.

Biotech – The Biotech Growth Trust (BIOG) is up 700% over ten years. The Nasdaq Biotechnology index has risen from 682 on 1 March 2009 to more than 3,700.

For David, biotech is not in a bubble because profits are rising. Since 2012, Alexion and Biogen have more than doubled earnings.

The top four biotechs in the Nasdaq index look decently priced – Biogen is the priciest at a PE of 20, while $161bn Gilead trades at just under ten times forward earnings. The average PE for the four is 14, the same a regular US pharma.

New cancer treatments, ongoing merger activity, product-starved big pharma drug pipelines, new genomic treatments, and ageing populations are all good reasons to buy.

American tech stocks – Tech stocks have had an amazing two years, but David says that’s because top companies’ profits are powering ahead. Some valuations do look a bit toppy, but this is not a bubble.

A disproportionate number of US tech companies have been beating estimates for both sales and earnings per share, compared to the wider market.

The sector trades on a forward p/e of 16, below the 17.8 for for the S&P 500. Global tech valuations are higher than the US at 16.4.

David refers to a paper by Ed Maguire of investment bank CLSA called 2020 forces converging: Crossing creative disruptions. Maguire thinks key trends will speed up as “everything becomes software”. Nanotechnology, the sharing economy, genomics (personalised medicine), intelligent machines and the internet of things are all reasons to be cheerful.

China – Here, David admits that the bubble case looks a bit stronger (see above). Valuations are high, but David believes that the recent surge was from a low base and has merely made Chinese equities reasonably priced, rather than wildly expensive. For example, many firms in banking and insurance are valued below their American and European peers.

I think we’ll have to agree to disagree about China. Bonds is a difficult one – there will be a crash at some point, but I agree with David that we are not likely to return to pre-2007 levels any time soon.

Tech stocks and biotech stocks are much easier to see as decent long-term bets, if you can choose the right stocks or funds. This is not dot com 2.0, but that doesn’t mean that things are cheap right now.

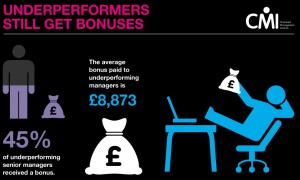

Large bonuses are bad incentives

In the FT, John McDermott wrote about why large bonuses lead to bad behaviour.

The annual pay survey from the Chartered Management Institute – which surveyed of 72,000 employees in 372 companies – suggests that the adoption of “performance-related pay” over the past few decades has been a giant experiment in behavioural psychology.

The survey found that the biggest predictor of whether a manager received a bonus this year was not the money they brought in, but whether they received a bonus last year.

This is the result of framing – the influence of what has happened before on future decisions.

Richard Thaler, a behavioural economist at the University of Chicago showed that a early win on at a night in the casino would be treated as the house’s money rather than our own, and we would most likely keep making large bets.

With bonuses, the two reference points are what what our colleagues get, and the gap between our expectations and what actually happens. Since our expectations are influenced by last year’s result, that becomes important.

As Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed, the fear of losses looms larger than the love of equally sized gains. Since companies are worried about upsetting their staff, this year’s bonus is related to last year’s.

This is the same argument made by Truman F Bewley in his book Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession (1999). Companies worry about morale and don’t want to risk demotivating employees and reducing productivity through a cut in wages.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0674009436&text=Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession?&template=thumbnail]

Surprising employees seems to be the way forward. In a 2014 paper, researchers from Harvard gave three sets of workers the same task, only varying the hourly rate: $3, $4 or $3 plus a surprise raise to $4. The last group worked harder than the other two.

Gifts are good too. Alexander Pepper, a professor at the LSE, says that small “recognition awards” are more motivational than their value would suggest.

Employees would rather a large gift (bonus) than a small one, but Dan Ariely found that high incentives only increase productivity on simple tasks. For complicated, cognitive tasks, “high stakes” led to “big mistakes” – people choke, as they sometimes do in sport.

On approach worth exploring is loss aversion. In 2012, Roland Fryer from Harvard paid teachers in advance for improving pupils’ grades. If they then failed to do so, they had to hand the money back. This worked significantly better than payment at the end of studies.

Inequality

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0674504763&text=Inequality: What Can Be Done?&template=thumbnail]

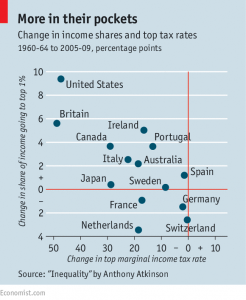

The Economist looked a a new book from Sir Anthony Atkinson, a mentor of Thomas Piketty. Inequality: What Can Be Done? is a shorter book than Capital in the 21st Century, but even more radical.

Sir Anthony calls for increased taxation of the rich whom he reckons have got off easily over the last generation. He believes government should influence the distribution of economic rewards. His policies – employment guarantees and wage controls – would be extreme even for the 1970s.

His thesis is that income gaps have three effects:

- they unfairly punish those who suffer bad luck; this seems reasonable, if only we could get two people to agree on the meanings of “fair” and “luck”

- they undermine economic growth and social cohesion (two very separate issues, in my opinion)

- inequality in economic resources translates directly into inequality in personal opportunity; this seems to be a basic gripe that rich people are safer and happier, and more able to indulge themselves, which pretty much seems the point to me

Covering the history, the book finds that inequality was high before the second world war, then low until 1980, when it began to grow again. ((Only within rich countries – inequality between countries, and global inequality between rich and poor is still falling))

The key driver was working women. High-earning men had tended to marry low-earning women as as women joined the workforce, their wages reduced household inequality. From the 1980s on, rich paired with rich and rising female participation exacerbated inequality.

Sir Anthony’s focus is the ways the rich are able to influence government policy: prioritising low inflation over low unemployment, or low taxes over investment in infrastructure or education.

He makes a number of recommendations:

- He argues that long-running trends like globalisation and technological change should not be taken as given. Rather than sponsor research that leads to autonomous vehicles (which may eliminate millions of jobs), research funding might be direct into factory technologies that complement the skills of blue-collar workers.

- The state should invest in human capital—in education and training—and emphasise the advantages of human interaction. For Sir Anthony, the ability to file tax returns online is a boon to the rich, but the need to file benefit applications online may be a burden to the poor.

- He recommends employing people to help the poor understand how to obtain benefits; this would both reducing the socially isolating effect of technology and creating public-sector jobs. This is surely putting the cart before the horse.

- He believes in a maximum wage as a multiple of the minimum, which I could go along with. ((Assuming the multiple is 10 to 20, and not 2!))

- He believes in a form of basic income termed “participation income”, paid to all those deemed to be contributing to society (through work in the market or public service).

- He would provide guaranteed employment, in the public sector if necessary, to those who want it. It should not matter whether the employment provides skills valued by the private sector, or whether the worker ever leaves the public sector.

As the Economist notes, it’s hard to see how policies that raise the cost of goods and services can truly help the poor. The line between limiting the power of entrenched interests to manipulate markets and a general dislike of markets has been crossed.

Until next time.