The Future of Pensions

Today we’re going to look at the government’s consultation paper on tax relief and the future of pensions.

Contents

Preamble

I’m a little late to this party – several other UK finance bloggers (such as Monevator, diy investor (uk) and Simple Living in Suffolk) have already weighed in on this topic. But it’s a twelve-week consultation, so it doesn’t matter that I’m a slow starter.

The government paper is called Strengthening the incentive to save. The subtitle is “A consultation on pensions tax relief”, and this appears to be the main focus of the review, rather than further structural changes to the pensions system.

The cynical view

Before we look at what they have in mind, we need to consider motivation. Some would say that the only time anyone holds a consultation is when they have already decided what to do. So what might be on the cards?

Even before this paper was published, we have the regular pre-budget speculation to go on. Despite the massive changes to pensions over the first five years of this government (mostly good changes, as far as I’m concerned), many commentators still see them as fair game for more tweaking.

The most popular options include:

- a flat rate of tax relief for all

- this would mean replacing the current 20% and 40% reliefs ((For the sake of simplification, I won’t concern myself too much with those earning more than £150K pa)) with a rate of 30% or 33%

- NIC relief on salary sacrifice and employer pension contributions to be restricted / withdrawn

- this “loophole” boosts the effective tax relief to 32% / 42%

- it was restricted for those on salaries over £150K in the summer budget

- restrictions on access to 25% tax-free “lump sum” ((It doesn’t need to be taken as a lump sum any more)) when crystallising pensions

- this would have to be phased in on an “accrued rights” basis – money already committed to a pension was contributed (up to 30 years ago) on the basis this relief would be available

- switching from EET to TEE, ie. imposing the ISA system on pensions

- at the moment money put into pensions is Exempt from tax (you get tax relief up front)

- once inside the pension it grows free of tax (Exempt again)

- when you take the money out to spend, you are Taxed – apart from the 25% allowance

- ISAs work the other way around – you are taxed on the money before you put it in and there is no tax when you take it out

- it’s likely that switching to TEE would involve a government top-up on contributions, to distinguish pensions from ISAs

- presumably this top-up would be less than the 40% relief so as to save the government money – the basic rate 20% relief seems plausible

Less likely changes include:

- further restrictions to the lifetime allowance

- The £1M lifetime limit is now only sufficient to produce an annual income of £31K (single life annuity at age 55, 3% escalation, 5 year guarantee) ((Source: Hargreaves Lansdown, 29th July 2015))

- this is barely above the national average salary (£27K) and so is unlikely to reduce much further – on current plans the £1M allowance will be indexed to CPI inflation from 2018

- there is an argument that the lifetime allowance should be based on contributions, and not on what size the pot grows to

- further restrictions to the annual allowance

- £40K pa means on average 10-15 years of contributions to eventually grow a pot that approaches the lifetime limits

- this is plenty for the “Steady Eddies” ((Name courtesy of Ermine from Simple Living in Suffolk)) who contribute each year from age 25, but restrictive for the “Catch-up Charlies” ((This name is my own)) who start saving seriously after age 40

- there is also the decent £15K annual ISA allowance to add into this equation

- Steve Webb, the ex-pensions minister, has speculated that alongside a switch from EET to TEE, those with large existing (EET) pension pots would be offered the chance to convert them to TEE by paying a one-off levy that would shelter them from all future tax

- if pitched correctly, this might be tax-neutral in the long-run but cashflow positive for the Treasury in the short-term – but the calculations would be difficult to get right

While we are in cynical mode, we need to think about what the government’s real objectives are. They want to make people save so that they are not a burden on the state:

- the new state pension is £8K pa (and “triple-locked”); over time almost everyone will qualify for it, but £8K is not enough to live on

- the government needs everyone to save enough to generate another £8K to £12K pa ideally, but at least something

- they particularly need to incentivise low earners, who will otherwise spend everything

- poor earners seem to be less motivated by tax relief up front, and often don’t realise that pensions are taxable

- generating say £10K per year will still mean saving a pot of around £200K to £250K by age 65 (or more cynically, £125K by age 75)

- over a working life of 40 to 50 years, this only requires annual contributions of £1.5K to £3K, which is not insurmountable

At the same time, lots of up-front tax relief and too much deferred consumption will not do much towards balancing the budget or stimulating the economy. So steady long-term changes are more likely than sudden shocks.

Recent history

The report covers the recent changes in the pensions landscape which have prompted the review:

- life expectancy has increased dramatically, and this trend is expected to continue

- a man aged 65 can expect to live for 21 years, and a woman for 24 years

- DB pensions have been replaced by DC pensions in the private sector

- in the public-sector, DB schemes remain, but final salary schemes are being replaced by career-average salary schemes, which reduce the burden on the state

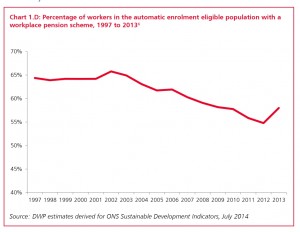

- workplace auto-enrolment (opt-out) has been introduced, which has increased scheme membership

- planned auto-enrollment contribution rates will peak at 8% from 2018; it’s likely that contributions of 12%-15% will be necessary in the future, and at least some of this may need to be compulsory

- the “pension freedoms” to access your pot after age 55 have been introduced

- the use of cheap ETFs and lower-cost mutual funds (following the RDR) in ISAs and SIPPs is now widespread

Tax relief

The “cost” to the Treasury of providing tax-relief on pensions is close to £50bn a year.

This has not risen in recent years, because the annual allowance has been reduced from £255K in 2011 to £40K now, and the lifetime allowance has come down from £1.8M to £1M.

In fact this is not the real cost, since much of the tax relief is merely deferred until retirement. Some retirement spending is tax-free, and some will be at lower rates than during the pensioner’s working life. NICs that have been avoided will also not be reclaimed.

But the total saving is much less than the initial hit.

The government is concerned that only one-third of the existing relief goes to basic-rate tax-payers, but this is partly due to changes in the tax system:

- the tax-free personal allowance was raised dramatically during the last parliament, reducing the amount of relief available to those on low incomes

- in parallel the higher-rate threshold was reduced to compensate for the loss in tax, dragging more people into the higher rate band

The rising contribution to relief costs from NICs shows how widespread salary sacrifice and employer contributions have become.

Principles for possible reform

The report concedes that the current system may be the best, but also sets out some (potentially conflicting) principles for designing alternatives:

- simplicity and transparency

- this should increase the incentive to save

- people don’t currently engage with pensions since the benefits are so far off in the future

- TEE (with top-up) might be an easier system for people to understand than EET

- personal responsibility

- people need to make sure they save enough for retirement

- builds on automatic enrolment

- the sounds like any new system should “nudge” people in the right direction

- sustainability

- at the very least, it shouldn’t cost any more than the current system

- the demographics are unfavourable, so even the current system is under threat

The questions

The report concludes with a list of eight questions built around these four principles, which respondents are encouraged to answer.

Simplicity and transparency

Monevator has some useful ideas about how to make the good deal that pensions represent a bit more obvious to the average person.

He wants to layout a section on the payslip something like this: ((I’ve adapted his idea slightly))

You saved £1,000 Your employer added £1,000 The government added £250 Cash boost = £1,250 Total Saved = £2,250 Every £1 saved now is the equivalent of £2 when you retire. The average person should save 15% of income to have a reasonable chance of retiring on 75% of their current income. You are currently saving 8% of income. Please talk to HR if you would like to save more.

That sort of thing should certainly help.

Conclusions

- Despite its title, this consultation is primarily about ensuring that the pensions tax relief bill doesn’t increase

- Since those on low incomes (in particular) don’t save enough, they need to be incentivised, compelled or both

- Those on larger incomes must have less incentive as a consequence

- It’s likely that a flat rate of tax relief on pension contributions – 30%? – will be introduced

- It’s likely that the 25% tax-free allowance will be phased out for new money

- The government should compel all workers to save 10-12% of their income (including employer contributions and tax relief) into a workplace pension, up to an annual saving of say £3K

- This saving scheme needs to have simple transparent reporting in present and future cash terms

- The annual voluntary pension allowance could be reduced to match the ISA allowance – total annual savings of £30K should be as much as the government needs to incentivise

- Switching pensions from EET to TEE would require the 30% tax relief to be converted into a government subsidy of at least 20% overall ie.25p per £1 saved

- this is cheaper than both the existing system and a flat 30% tax relief, which might make it attractive to the government

- Tinkering with the tax system is less important than educating young people about the importance (and the mechanics) of saving

- Working against the incentive of tax relief / topping up is the restriction on accessing pension funds before age 55

- the government might ease this by defining circumstances (eg, ill-health) under which access is possible

- The other problem with pension saving is the uncertainty of returns

- a national low-cost multi-asset pension vehicle with modest returns (inflation plus 4%) guaranteed by the government would go a long way towards restoring confidence

Until next time.