Weekly Roundup, 28th July 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with the Chart of the Week in the FT, which showed five years’ history of the gold price.

Contents

Gold price

Lucy Warwick-Ching took a look at the gold price, which hit a 5-yr low of $1,088 last week. The price is now down 42% from the peak of September 2011.

There are several factors involved in the decline:

- the strength of the dollar – gold and the dollar two have an inverse relationship since gold is normally priced in dollars

- gold is also generally regarded as an “alternative currency” that acts as a safe haven when fiat currencies like the dollar are under pressure

- the dollar is increasingly popular given the prospect of an interest rate rise in the US within the next few months – the increasing yield on the dollar makes yield-free assets like gold less attractive

- political risk is receding as the Grexit crisis passes and a nuclear deal with Iran is agreed

- gold is also seen as a hedge against inflation, which is not a threat at present

- gold is also suffering from the crash in all other commodities markets

- the Chinese government claimed last week to own “only” 1,658 tonnes of gold bullion (1.65% of Chinese FX reserves, up from 1.1%) – far less than the 3,500 tonnes the markets were expecting; for comparison, the US holds 8,133 tonnes

Income vs total return

Terry Smith delivered the second part of his opinion piece on income stocks. Terry accepts the conventional thinking that dividend-payers out-perform, but stresses the importance of understanding why. Correlation is not causation.

There are two kinds of non-dividend payers:

- companies without the profits & cash-flows to do so

- companies that prefer to reinvest profits back into their business

These two groups are very different, and the performance of the first group is likely to drag down that of the second.

Terry thinks that the real comparison is between dividend-payers and re-investors. He would also add a third group – modest dividend payers who mostly re-invest.

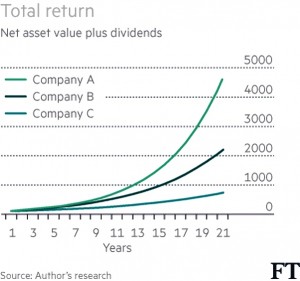

In the chart above:

- Company A makes 20% return on capital and re-invests 100% of this

- Company B makes 20% return, but pays out 30% as dividends, re-investing 70%

- Company C makes only 10% annual return, but re-invests it all

A is the best performer as expected. More instructive is the result that B beats C – the rate of return on re-invested capital is more important than the dividend payout rate.

The stock market ratings of the three firms (PE) are likely to magnify the NAV differences, so the entry price for the best firms will be higher, but over the long-term the superior return on capital will win out. ((Terry covered this in a previous piece on bond proxies))

Terry thinks that the search for yield represents a psychological block in investors, a feeling that they can only safely spend the income from their portfolios.

But high-yield is usually risky, and investors would be better advised to look at total returns, and to regularly convert a portion of their portfolio to cash, for use as income.

P2P investment trust raises £400M

Judith Evans reported that the investment trust P2P Global Investments (LON:P2P) had raised an extra £400M rather than the planned £250M.

The trust now has a market cap of £900M, putting it into the top 30 investment trusts within a year of its launch. It currently yields 4.2% but is targeting 6% to 8%.

Other P2P investment trusts are VPC Speciality Lending (LON:VSL) and Ranger Direct Lending (LON:RDL) which focuses on lending to US businesses.

Buy to let

Patrick Jenkins was worried over the future of buy to let. Patrick has a seaside cottage in Wales, but doesn’t cover his costs by renting it out when not in use. It’s not the typical buy to let story.

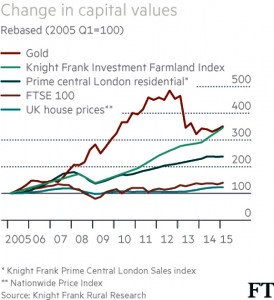

Returns over the past 18 years have been spectacular – almost 1400%, compared with 210% for equities and 230% for bonds. Admittedly, this is with gearing (typically a 75% mortgage), so a better comparison would be 800% – 900% for bonds and stocks.

Even now house prices are rising at 5.6% per year, and average yields nationally are still above 5%. Buy to let mortgages are as low as 2%, and now make up 15% of the nation’s property debt.

But the headwinds are starting to appear:

- interest rate rises are on the horizon, and mortgage payments could easily double over the next few years

- this increase could in turn halt the rise in house prices

- distressed buy to let sellers could even send the market into reverse

- the budget has removed higher rate mortgage interest tax relief, significantly reducing yields for higher rate taxpayers

Perhaps we have finally reached peak buy-to-let.

Farmland

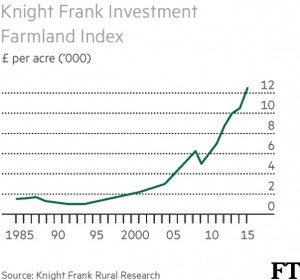

James Pickford took a look at farmland as an investment. Farmland used to be dull, with an annual yield of 1%-2%.

But in recent years its value has rocketed, and now stands at £8K per acre, compared with £1K in the early 1990s. The best land in England, in larger blocks (> 1000 acres) now sells for £12.5K per acre.

Gains over the past decade are even higher than prime London property.

The factors behind the rise include:

- finite supply

- population growth and hence increasing demand for housing

- increasing global demand for meat, which needs more land for its production

- relative stability in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008

On the ground, prices vary widely according to whether adjacent owners are interested in buying, and the elevation, quality and crop yield of the land. Land is graded from 1 to 5, with Grade 3 the most common (50% of the total).

Tenants’ rights of succession are also a factor, and farms with “pre-1986” tenants are only eligible for 50% agricultural property relief.

Farm income and cash flows are lumpy, and farmers typically supplement their income with side businesses. Farm shops are common, and renewable energy (particularly wind turbines, but also solar) have been popular in recent years.

The rules on converting farm buildings to residential use have also been relaxed.

UK investment buyers face competition on four fronts:

- foreign investors (especially from Germany and Denmark) are showing interest, since UK land is cheaper than their local land

- adjacent farmers are taking advantage of low-interest rates to extend their exiting farms

- institutional investors (pension funds) are moving back in to the market from commercial property

Angel investing

The FT also looked at how to become an angel investor. Angel investing is widely known these days – it’s on the telly, in Dragons’ Den and The Apprentice.

Famous companies that have taken money from Angels include Zoopla and Lovefilm (bought in 2011 by Amazon for almost £200M).

The size of the market is unclear, but in 2013/14, 4,500 companies received £1.55bn through EIS and SEIS, up from around £1bn the previous year.

- EIS offers 30% tax relief up front (to a maximum of £1M per year), if the shares are held for 3 years. Profits are free of CGT

- SEIS funds earlier stage (smaller) companies and offers 50% tax relief on up to £100K per year, if the shares are held for 3 years.

Angels are not like arm’s length investors. They often want an active role in the business they invest in, providing advice and contacts as well as cash. There are four main types of investor:

- entrepreneurs, with a cash exit by 40; they have spare money and the experience of running their own company

- the professionals – accountants and lawyers with some spare cash and some relevant expertise; people from advertising and marketing are also in this category

- City people, from private equity or running a family office (inherited wealth); for these people it’s a career rather than a hobby

- the crowdfunders, who are mostly first-time “high-street” investors – this is not real Angel investing

Syndicates are popular because they pool risk and expertise. The greater scale of funding within a syndicate also provides access to better opportunities. Average first-time investments are £30K to £40K, often split in £10K chunks between syndicates.

Bonds

James Mackintosh was worried about the risks to investors holding bonds should the global economy recover.

Markets are priced for stagnation, low inflation and low interest rates. There may be rate rises ahead in the US and then the UK, but they will be small and slow. The markets (bons, swaps and futures) are predicting that US rates will be around 1.7% at the end of 2017.

James looked at four different scenarios for change:

- inflation increases without growth (stagflation)

- gold would do well and bonds badly

- the economy grows faster without inflation (Goldilocks)

- shares and corporate / junk bonds do well, government bonds are mediocre

- central banks tighten policy anyway (mistake) when there is no need

- everything but cash would do badly

- normality returns (inflation and higher interest rates)

- shares do well (especially cyclicals) and bonds suffer

There aren’t really any options where government bonds do well.

Minimum wage

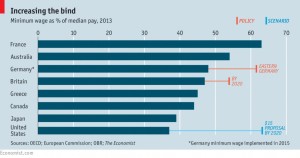

The Economist had not one but two articles about the minimum wage. Their basic issue is that set too high (above 50% of median full-time income), a minimum wage will reduce demand for labour and destroy jobs.

They have a point, but on the flip side, the current support for low wages (eg. the tax credit system in the UK) is dissuading companies from investing in the automation needed to displace low-skill workers, and is therefore contributing to the “low productivity puzzle”.

We need to grasp the nettle that many workers will be too unskilled to participate in the economy of the near future, and decide what we are going to do about it.

Tech boom

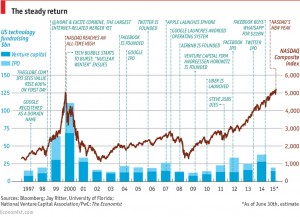

The newspaper was more reassuring about the chances of a crash – like the dot-com bust of 2000 – following the current tech boom.

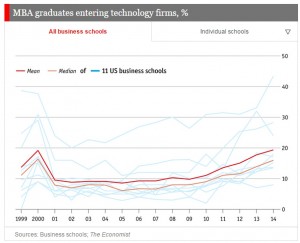

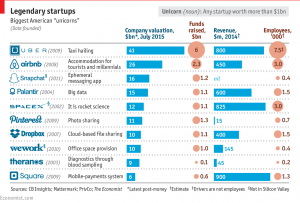

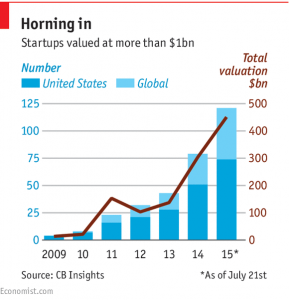

Uber (age 6) is valued at $41bn; Airbnb (7) is worth $26bn. Almost 20% of business school graduates go to work for tech firms, just as in 2000.

The NASDAQ has hit a series of all-time highs, and people worry that it cannot last. Prices have escalated – Facebook bought Instagram for what seemed a ridiculous $1bn in 2012. Last year they paid $22bn for WhatsApp, a firm with only $10M of sales.

The difference this time is that the tech firms already have sales and profits, rather than the projections and promises of 2000. And the people giving them the money are a much smaller group than last time.

This concentration obviously has its downside – the ordinary investor can’t get a piece of the upside, and firms are protected from public scrutiny – but it means that any damage from a bust will be concentrated.

IPOs are now of firms that are 11 years old and have $91M of sales. In 1999 the firms were 4 years old with sales of $17M. There were 632 tech IPOs in 1999-2000, and 29% doubled on day one. In 2014 only two of 53 IPOs doubled. The average PE of the $1bn “unicorns” is 21, compared to the 170 the NASDAQ reached in 2000.

Its also the case that the internet is now more widespread (3.2bn users rather than 400M) and more pervasive – more intimate – than it was. The rise of the cloud keeps startup costs down, and marketing via social media is cost-effective.

The beer pill

Thanks to a random link on the web, I came across a post from the beginning of the month on Flip Chart Fairy Tales. It was about Andrew Fastow, the CFO of Enron, who gave a speech at Camp Alphaville, the “summer festival” organised by the FT.

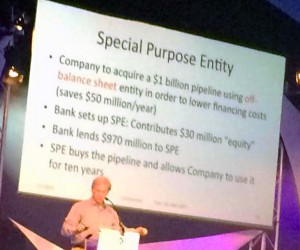

During the speech he held up his CFO of the Year award from 2001, and then his prison ID card. He had been given both for doing the same things. He was the “Chief Loophole Officer” responsible for off-balance sheet financing.

The photo above describes a typical example:

- instead of borrowing $970M to fund a pipeline, Enron gets its bank to set up a Special Purpose Entity (SPE) – a company that the bank can lend the money to

- the bank contributes $30M equity as well to comply with a “3% outside investment” rule

- the SPE buys the pipeline and Enron leases it from the SPE

- the bank has lent the money, and Enron has paid it a fee to do so, but it doesn’t count as a loan to Enron

- so it doesn’t appear on Enron’s balance sheet, and Enron’s accounts look stronger than they should

Fastow recalled how he explained what he had done to his 15-year-old son:

- let’s say you (the son) have a rule not to drink at parties

- other kids try to persuade you but you stand firm

- then a kid explains he has an alcoholic, beer-flavoured sweet

- if you chew that, you wouldn’t be drinking alcohol, and you wouldn’t have broken your rule

Fastow’s son agreed that this was not OK. “Well”, said Fastow, “I’m the guy who chewed the beer pill.”

The problem is that lots of people in 2001 were chewing the pills, and if you weren’t, your balance sheet was at a disadvantage.

Fastow now teaches business ethics and he get students to work out the debt-to-asset ratio for a company. Then he gets them to examine the footnotes, and add in the off-balance sheet debt. In the example he uses, this doubles the ratio.

The students think this is unethical and say that they wouldn’t work for the company or invest it it. Then Fastow explains that the “company” is their own university. They want to complain, until Fastow explains that fees would have to rise by about 10%.

Suddenly they want to ignore the issue. It takes 4 minutes for them to sell out.

Until next time.