Stock Market Profits 2 – Earnings, Momentum and Insiders

Today’s post is our second visit to The Little Book of Stock Market Profits by Mitch Zack. Today we’re going to look at earnings estimates, momentum and insider trades.

Earnings estimates

What ultimately gives a company’s stock value are the earnings the company generates. It is completely determined by the potential cash flows that are due to the owner of the stock.

The size of the potential dividend payments is driven by whether the underlying company behind the stock is generating earnings.

Earnings estimates reflect the market’s best guess at what the future earnings of a company are going to be. So they drive stock prices.

Buy side firms (eg. fund managers) have no incentive to publish their research.

- But sell-side firms (brokerages) have economies of scale because they have many similar clients.

So research has concentrated on the sell-side and becomes semi-public information.

- Buy-side analysts collate research from many sell-side analysts who each cover only a handful of stocks.

- And private investors can do the same.

Compared to buy / hold / sell recommendations, earnings estimates are relatively unbiased (and for smaller companies in particular, are often sourced from the firm itself).

- Analysts don’t want to upset the companies they cover, or predict disruption to an industry they have studied for years, but their earnings estimate should be reasonably honest.

That doesn’t mean they are without bias.

- They are too optimistic and tend to be revised downwards more than upwards.

As well as developing a version of Stockholm Syndrome in relation to the companies they cover, analysts also tend to over-weight the persistence of earnings from accruals (as opposed to cash).

The basic technique for investors is to use revisions to estimates from multiple analysts.

- You’re looking for multiple upward revisions to buy.

Stockopedia makes this easy, both visually (in the Stock Report) and within the Screener.

- Earnings revisions are also built into the Momentum Rank.

For some reason, the market under-reacts to earnings revisions.

- Mitch says this is due to serial correlation between revisions (momentum).

A stock that has received one upward revision is more likely to receive more, but the market might not react until it does (or the actual earnings report is published).

Going long the top 5% of earnings revisions and short the bottom 5% produces a market-neutral return of 10% pa (before transaction costs).

- The best results come from smaller companies and those covered by the fewest analysts.

- And “shock” revisions that are a long way from the pre-existing consensus have greater impact.

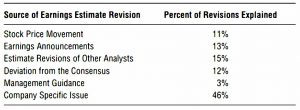

Mitch says there are five main reasons for revisions (though between them the only explain 54% of revisions):

- Changes in a stock’s price (11%)

- Due to some fundamental change in a stock’s earnings prospects, the stock’s price will go up.

- Earnings Announcements (13%)

- Revisions from other analysts (15%)

- This is herding and avoiding career risk – analysts like to change their opinions gradually on step with others.

- Reversion towards the consensus (12%)

- More herding.

- Unexpected guidance from corporate management (3%)

Looking internationally, Mitch singles out the UK as one of the most profitable markets for exploiting earnings revisions.

Price momentum

Stocks whose price has risen tend to keep on rising, at least for a while – “the trend is your friend”.

People who believe in the efficient market hypothesis have problems with momentum.

- They believe that each price movement is independent of what has gone before.

I don’t – you just need to look at the sharp recoveries that usually follow large market crashes to see that they are linked.

- Or the wild over- and under-valuations themselves.

Apart from price momentum, this issue is very significant in decumulation.

- Monte Carlo models use independent price movements and so exaggerate the safe withdrawal rates that are possible from pension pots.

Make sure the analysis you are looking at uses historical data instead.

The data shows that over six months, stocks that have gone up carry on going up, but over three to five years, they go down again.

- This is momentum and then reversion to the mean.

As they say, timing is everything.

Mitch reports that market-neutral momentum portfolios generate 12% pa before costs.

- Momentum works better on the long side than the short side.

It also works best with mid-cap stocks rather than the largest or smallest stocks.

- And it works best for stocks with lower analyst coverage.

It doesn’t always work, however – big crashes like 2000 tend to disrupt momentum.

Momentum also works best during periods of economic expansion, and turns negative during recessions.

Sadly, recessions are not easy to predict with precision.

Mitch explains momentum’s outperformance by reference to investor behaviour.

- People hang on to losing stocks too long, and sell winners too soon.

This tallies with the finding that low volume stocks (more likely to be held by individuals) show the momentum effect more strongly.

Mitch says that the best strategy is to use 12 months of price history to generate a portfolio that is held for the following three months.

- This is known as a 12/3 split.

- A 6/6 split also works well.

Even better is a strategy of buying stocks near their 52 week highs and well above a long-term moving average.

- Mitch suggests 120-day or 240-day, but I prefer 150-day and 200-day.

Momentum returns are not correlated across international markets, which suggests that they are not driven by macroeconomic factors.

Insider trades

Buying publicly traded equity is a lot like purchasing a used car. The seller knows a lot more about the car than you do – whether or not it is a “lemon”.

The people who truly know the value of the company are its executives and the investors with the most stock in the company.

Mitch calls copying the trades of these insiders piggybacking.

- We’ve already used that term for copying trades in public portfolios, so we’ll stick with calling them insider trades.

If the insiders of a company are buying, you should be buying as well, and if the insiders are selling, you should probably be avoiding the stock.

Mitch reports that insider trades generate an excess of 6% in the first six months after a purchase.

- A third of this comes in the first month.

Following insider buying works better than insider selling.

- This makes sense, as there are lots of reasons why an insider might need to sell, but few justifications for buying.

Directors and owners of more than 10% of the stock are the best people to follow.

- Multiple purchases (three within three months, say) have more predictive power.

Insider trading works better where there is a greater degree of information asymmetry. It won’t work for companies whose earnings are primarily driven by large macro economic factors (oil, say).

Sectors like biotech are more promising.

Insider buying seems to be most predictive in the transportation, consumer staples – including drug companies, technology, financial, and business services sectors.

Conversely, insider buying is least effective in the capital goods, basic materials, energy, consumer cyclical, and utilities sectors.

As usual, insider buying works best with smaller companies.

Especially in the US, insiders used to have a lot of time to report transactions, but since 2002 they’ve had only two days, which makes following insider plays much easier.

I don’t have a good free source for UK director dealings, but I’ll look for one when we come to implementing the strategies from the book.

Mitch recommends weighting your insider purchases in proportion to the amount of money invested by the insider.

Conclusions

It’s been a breezy and interesting visit to Mitch’s book, with three good trading ideas.

- I’d come across them all before, but reading a book like this does focus the mind on implementation.

I’m already a big user of momentum, but I need to do more with earnings revisions and director dealings.

I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with the next three chapters of the book, which look at stock issuance and buybacks, earnings quality and valuation metrics.

Until next time.