23 Things About Capitalism – Things 1 and 2

Today, after several false starts, we finally begin to look at Ha-Joon Chang’s “23 Things They Don’t Tell You about Capitalism”.

Contents

23 Things

This is the book that I told you I read on my June holiday in Italy.

While it doesn’t claim to be an introductory economics textbook (Econ 101, or as Ha-Joon calls it, “economics for dummies”), it does introduce a lot of interesting concepts.

- And from the perspective of a very-left wing Cambridge professor with a bee in his bonnet about helping the third world to develop.

- And all without much maths.

So there’s lots to like.

But before we start it’s worth remembering the context in which the book was written, back in March 2010.

We were still in the midst of the financial crisis back then.

- To put it simplistically, the FTSE-100 peaked in 2007 are around 6,730.

- By March 2009, it was down to 3,530 – a fall of more than 47%.

- When Ha-Joon wrote his book, the FTSE-had recovered to 5,700 – up 60% from the bottom, but still down more than 15% from the 2007 peak.

So it was still a bear market, though things were getting better.

- Since then we’ve had a peak of more 7,000 in April 2015, and as I write this in July 2016, the FTSE is just below 6,700 (despite the recent Brexit vote).

Ha-Joon writes about the financial crisis in his introduction.

- He accepts that fiscal and monetary stimulus has prevented a re-run of the Great Depression of the 1930s, but he’s not convinced that a sustained recovery is certain.

- There are financial bubbles around, and “the real economy is starved of money”.

- He expects reduced public investments and welfare entitlements.

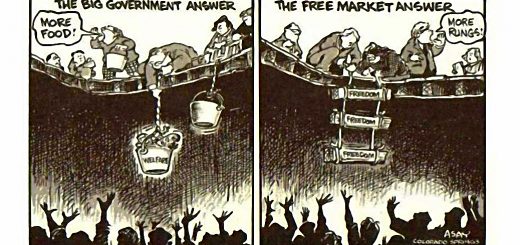

Most importantly, he blames the “catastrophe” on “the free-market ideology that has ruled the world since the 1980s”.

- He doesn’t trust markets to “produce the most efficient and just outcome”.

Free markets

As described by Ha-Joon, the two principles underlying free markets are that they are:

- Efficient, because individuals know best how to utilize the resources they command, and

- Just, because the competitive market process ensures that individuals are rewarded according to their productivity.

More freedom for businesses will maximise wealth creation.

- Government intervention reduces efficiency, since governments have worse information and no incentives to make good decisions.

- He even quotes “the rising tide lifts all boats” metaphor.

Note that Ha-Joon is trying to paint free markets in a bad light here, but even prevented at its starkest, I find nothing to disagree with.

- Governments should only intervene to correct monopolies and externalities.

As well as the 2008 crisis, Ha-Joon blames free markets for slow growth and rising inequality, problems that were smoothed over in rich countries by credit expansion (more debt).

We’ll look at these claims in more detail in the future, but I will point out that inequality within a rich country (definitely a problem over the past 30 years) is not the same as global inequality (which free markets have helped to fix).

Ha-Joon claims not to be against capitalism, only free markets: “I believe that capitalism is still the best economic system that humanity has invented”.

We shall see.

- I invite you to make your own mind up about what Ha-Joon – and you yourselves – think at the end of this series of articles.

Ha-Joon has 23 Things that he thinks are wrong with free-market capitalism.

- I’ll be scoring him on each of the things to see how many he can convince me of.

Note that Ha-Joon is a developmental economist and so tends to take a global view of things.

- As befits a UK-focused website, I’ll be restricting myself to a UK view of markets, and of economics generally.

Thing 1 – Markets should be Free

Ok, let’s start with the most basic Thing.

The Free Market position is obviously that markets need to be free.

- Government intervention prevents the most efficient allocation of resources (particularly capital).

Ha-Joon uses the example of private rentals.

- If rents are capped ((As London Mayor Sadiq Khan has hinted )) then landlords will not invest in rental properties.

- They will cut back on maintenance, they will not build more properties to rent, and they may sell some that they have.

- Profits are what incentivise action.

Or if certain transactions are prohibited – Ha-Joon focuses on financial instruments, but let’s widen this to things like the “repugnant transactions” (eg. kidney sales for transplants) that we discussed under market design – then both parties who might have made a contract will not reap the potential gains.

Thing 1b – No such Thing as a Free Market

Ha-Joon says that free markets don’t exist: “every market has some rules and boundaries that restrict freedom of choice.”

- Markets only look free because we agree with the restrictions, and so we don’t see them.

He uses the example of child labour, which was commonplace in England until the 1919 Cotton Factories Regulation Act. ((Despite the Act, my own grandmother began part-time work in a cotton factory at age 4, in the year 1900 – she went full-time at age 8))

- So because people under 16 can’t work, there isn’t a free market in labour.

He’s got a point, but so have the Free Market gang.

- Because youngsters don’t work, we are not maximising our labour efficiency.

We may choose as a society to do that – I’m sure there aren’t many parents who would be in favour of sending their children to work – but it doesn’t change how markets operate.

- Just as with a minimum wage, if you place restrictions on employment, labour will cost more.

And that may be great for our society, but it can equally impact the cost of the goods and services we produce, and hence our international trading position.

- China’s labour laws are better for trade than those in France.

Ha-Joon also tries to drag environmental legislation in here.

This is a red herring.

- Climate change and pollution are externalities, and free-marketeers should have no objection to government intervention.

Polluters should pay the costs of restricting or cleaning up their pollution.

- A carbon tax to limit CO2 production would be a good thing, assuming is could be applied globally.

- There would also be some clever thinking required on how to set a price that works for everyone. ((Sounds like a much bigger version of the Euro problem to me ))

Ha-Joon also thinks that the restrictions on trade (eg. narcotics, organs – the “repugnant” transactions we mentioned earlier) are “obvious”.

I would argue – and history would show – that they are nothing of the sort.

- They are social choices and conventions.

- And they vary from country to country and from time to time – they follow fashion.

Arguments could be made for legalising the trade in both narcotics and organs, not least of which is that many lives would be saved each year.

Other examples of regulations and restrictions (testing medicines, licences for doctors, restricting access to firearms, the slave trade) are not so controversial, though technically the same arguments could be made, with less support.

The key point is that these are all market restrictions which impede efficiency.

- We’ve just decided that the loss of efficiency is cancelled out by a gain along another dimension (eg. not so much gun crime).

Ha-Joon does have a good point about interest rates.

Since the 2008 crisis ((Remember, he’s writing only two years later, but we’re still in the same situation eight years on )) interest rates have been kept artificially low to stimulate demand.

- So the price of money (borrowing) is also set politically.

I think that an independent central bank setting interest rates is a good thing.

- Along with a sovereign currency (in which government debt can be denominated, and for which an appropriate exchange rate can be determined by the market) it’s a fundamental way of managing the UK’s economy.

But Ha-Joon is right that it’s not a “free” price.

Free trade and free labour

Immigration is an interesting one.

- Ha-Joon states that 80-90% of native workers would be replaced by cheaper immigrants in a “free” labour market.

- Instead, what he calls “political” restrictions are applied.

There are two points here.

- This highlights the difference in perspective between myself and Ha-Joon.

- For me, a free labour market for the UK doesn’t mean letting any workers in from outside that we don’t desperately need.

- Second, ((As we saw a few weeks ago )) the experience of the UK over recent years has indeed been that more than 90% of the new jobs created have gone to foreigners.

- This goes a long way towards explaining the “surprise” Brexit vote.

One of Ha-Joon’s points does stand – the control that the government has over immigration levels ((Non-existent in recent times for the UK, but hopefully somewhat better post-Brexit )) means that to some extent the level of wages is set “politically”.

- I see that as a good thing, while Ha-Joon does not, but it’s true in either case.

Ha-Joon correctly relates regulation to moral (or political values).

Many Americans currently believe that China is “cheating” at trade by paying workers unacceptably low wages and making them work in inhumane conditions.

- China would argue that cheap labour (working in terrible conditions) is their competitive advantage.

This is not an economic argument.

There’s no right or wrong here, but because my analysis focuses on the nation as the fundamental unit, I will at least say that the US has no right to impose its definition of “unacceptably low wages” or “inhumane working conditions” on a sovereign nation.

Thing 1c – Conclusions

We as a country (here in the UK) are free to place restrictions on a market, but these will have consequences.

- Just because a market isn’t free doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be free.

I’m going to give Ha-Joon half a point on this one.

- He’s technically correct, but hasn’t provided a good reason for why markets shouldn’t be free in general.

- Instead he’s chosen what he hopes will be an emotive example (child labour), plus a few red herrings (externalities and immigration).

Potential market restrictions need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, with the pros and cons fully explained.

Shareholders own companies (it’s their money).

- They are paid in dividends (a share of the annual profits), plus any increase in the value of their shares on the market.

- Unlike everybody else (employees, suppliers, lending banks and bondholders), they only get paid if there is a profit.

- They have “skin in the game” – if the company goes bust they get nothing.

So the idea is that running a company in the interests of its shareholders will mean maximum profits, which is the best outcome.

Thing 2b – No they shouldn’t

At root, Ha-Joon’s objection is that shareholders are “the most mobile of the stakeholders”.

- Because they can – and increasingly do – sell their shares at any time, shareholders rarely have a long-term perspective about the firm.

- They will support policies that maximise short-term profits at the expense of long-term prospects.

I agree with him that short-termism is bad, but that’s not the same a shareholder focus.

He even seems to be against dividends, as they weaken “the long-term prospects of the company by reducing the amount of retained profit that can be used for re-investment”.

- Investment is only a good thing if it will be profitable.

Sometimes the right thing to do with a company is to let it shrink, or even die.

- Creative destruction – the replacement of bad companies with newer, better ones – is fundamental to capitalism.

- Zombies may be fun in the movies, buy they tie up crucial resources in a real-world economy.

Thing 2c – Discussion

Ha-Joon concedes that the limited company (as in limited liability – shareholders lose only their investment should it go bankrupt) is the basis of modern capitalism.

- Until the invention of the “joint-stock company” in the sixteenth-century, businessmen had to risk everything they had in a venture (including a spell in debtor’s prison).

- Starting a company wasn’t liberalised to the masses until the mid-nineteenth century, when enterprises needing a lot of capital (steel mills and railways) came to the fore.

The effect of the limited company was to scale up capitalism, from small factories employing a few dozen people into global corporations with many thousands of employees.

- Initially many of the best firms were managed by charismatic and talented entrepreneurs with a big chunk of the shares.

- Many people would like to go back to that form of capitalism, but with the best will in the world, founding entrepreneurs don’t live forever.

Adam Smith opposed limited companies on the basis that the managers would take risks with money that was at least partially not their own.

- Interestingly, Marx was in favour, since the limited company separated the capitalists (owners) from management.

- This meant it would be possible to eliminate capitalists (by transferring ownership) yet retain the benefits of capitalism and the company.

I’m with Adam to an extent.

- The real problem with limited companies is the “agency” problem.

- It’s almost impossible to incentivise management to do what is in the interests of shareholders.

Leaving aside the current issue of excessive boardroom pay, it’s easy to see that the use of share options has had unintended consequences.

- Executives are incentivised to support the share price – for example, through buybacks – rather than grow the business.

- They also tend to back glamorous “ego” projects, including unwise takeovers.

So rather than trying to stop companies working in the interests of shareholders, I see the problem as being that they don’t work enough in the interests of shareholders.

- Companies are nowadays run largely for the benefit of management, who form part of the bureaucratic and technocratic elite that siphons off any growth in global wealth.

What can be done to fix short-termism and the agency problem?

There’s no silver bullet.

- We could force executives to buy (rather than be granted) a substantial shareholding in their firm, which they must retain for 10 years.

- We might also ask companies to define their position along a short-term / long-term continuum, and sign up to one of two sets of regulations to enforce their behaviour accordingly.

- There are lots of (particularly) family firms that are operated for the long-run.

- And there are lots of investors who would and do support that approach.

It would be interesting to see which way the capital flowed under such a market structure.

Thing 2d – conclusions

I’m going to give Ha-Joon zero points on this one.

- He’s identified the wrong problem, and he’s running in the opposite direction.

I agree with Ha-Joon that the “shareholder value” experiment has failed.

- We need fewer share buybacks and share options for executives.

But the rasion d’être of a company remains providing value to its shareholders.

- A company is an artificial person, pooling the interests of its many investors.

- If you make it act in the interests of others, you won’t find many people willing to invest.

The real problem is in finding a way of encouraging managers to do this, rather than siphon off the spoils for themselves.

- We need to focus on long-term value to shareholders, rather than value to someone else.

- A company focused on long-term value will of necessity take into account stakeholders like workers and suppliers.

I get the impression that Ha-Joon is not himself a shareholder, and doesn’t understand their motives.

So that’s 0.5 out of 2 so far, a pretty poor 25%.

We’ll be back in a week or so with another three of the 23 things.

Until next time.