Excess Returns 9 – Types of Stock

Today’s post is another in our series on the lessons to be learned from guru investors. It’s about the various types of stock, and when to buy and sell them.

Contents

Types of Stock

Most bad companies stay bad, and most cheap stocks get cheaper. Once you realize that, then you’re ready for investing in turnarounds – Charles Kirk

In Chapter F of Excess Returns, Frederik looks at how to trade (or not) seven types of stock:

- stocks in various growth phases

- emerging (new) companies

- fast growers

- stalwarts (mature companies)

- slow growers (mature companies)

- cyclicals

- turnarounds

- asset plays

Special situation stocks have already been covered in an earlier article.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0857193511]

Company growth cycle

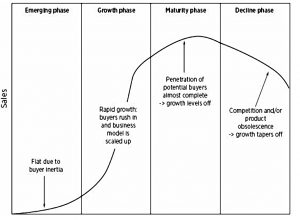

For those of you who have been to business school or work in marketing, the company growth cycle looks very like the product life cycle:

- New companies (Frederik calls these “emerging”, but I don’t like the potential confusion with emerging markets) begin with slowly growing sales

- If the company doesn’t run out of money, typically sales will pick up as the firm expands into new demographics, markets and geographies – this is the growth phase.

- Next the firm saturates its markets and becomes mature.

- Finally competition or new technology forces the firm into decline

Not all firms follow the model path, and the timescales will differ from firm to firm, but it’s a useful starting point.

New companies

New firms are unproven, and investors need to believe they will be successful before they actually are.

- Successful investors (those studied by Frederik) find new firms too risky.

- Their track record is too short to properly evaluate management, strategy and the business model.

- Management may well be inexperienced, even though it faces the toughest challenges, usually including richer and more experienced competitors, and massive customer acquisition.

Nor is first-mover advantage a guarantee of success.

- Frederik points out that McDonalds, Nike and Microsoft all “came from behind” in their respective industries.

Unprofitable firms should be left to private equity and venture capital investors.

Fast growers

Fast growers have demonstrated that their business model works (is profitable) and can be duplicated to other customers and/or locations (eg. a restaurant rollout)

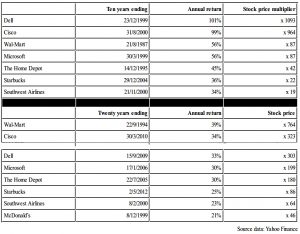

- These are the firms that growth investors look for – the fabled “ten-baggers”, though many can rise by a hundred times or more over 10 or 20 years.

In Frederik’s table, tech stocks like Dell and Cisco went up by 1000 times in the 10 years to the dot com boom, though they fell back later.

- Retailers like Wal-Mart and Home Depot also grew by 30% to 40% a year over 20 years.

Growth investing is hard.

- Even Peter Lynch admitted that four out of five of his growth stocks did not work out.

Timing purchases and sales of fast growers

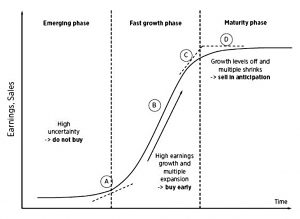

Although fast growers are largely buy-and-hold investments, for maximum profits you need to get your entries and exits right.

As the company enters the growth phase, buying early is a good idea if you are sure that the firm is transitioning.

During the growth phase, the multiple expands along with profits.

- You need to be on board by now, even if valuations are stretched by the time you buy.

- You should still be able to hold for years until growth rates start to slow.

As growth slows, multiples will start to shrink, and the share price will initially plateau.

- Institutional ownership will peak here.

- You need to sell as close to the start of this process as possible, and not at the end.

Once the growth phase is over the stock may move sideways for years, or start to fall.

- The stock may become a stalwart, slow grower or cyclical (see below).

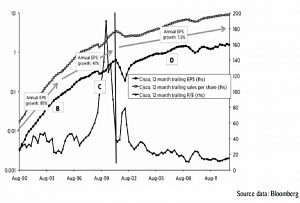

Frederik uses the Cisco chart to illustrate this process.

Growth stock selection

Private investors tend to look for growth stocks in new industries, particularly tech.

- Top investors often find tech too unstable and highly valued, and prefer sectors that are out of the spotlight.

They look for fast growers that can steal market share in slow-growth industries.

- Peter Lynch liked retailers and restaurant chains (firms like Wal-Mart, Home Depot, McDonald’s and Starbucks.

- These firms can grow at 20% a year for decades and are not easily challenged by new entrants.

- Hotel chains are similar.

Other things that top growth investors look for include:

- low gearing, which provides a cushion against inevitable misfortunes

- disciplined expansion rates

- plenty of room for expansion – get in while the firm is small and growing

- beating broker forecasts

- significant insider ownership

- stable senior management

- low institutional ownership to date

Red flags include:

- expansion into emerging markets

- blaming underperformance on things like the weather

- delays to expansion plans

- sales growth deceleration

- falling profit margins and returns on investment

High valuation (in terms of PE) are fine, but the PEG should generally be less than 1.

- Projected growth rates should not be more than 25% pa, since such rates are difficult to maintain for long.

Mature companies

Investors should stay away from firms in the transition to maturity, but once growth stabilises at a lower level, and valuations are lower, they can take another look.

- If growth remains positive, the firm will become either a moderate grower, a slow grower, or a cyclical.

- Moderate growers are what Peter Lynch called “stalwarts”.

Large cap mature firms should be preferred to small cap mature firms, since growth rates will be similar and bigger companies are safer on average.

- A large difference in valuation would of course affect this rule, as better future returns could be expected from a cheaper smaller stock.

Stalwarts

Stalwarts are large companies ($$$ bn) with long track records.

- They have a competitive moat that allows them to grow earnings and sales faster than the economy.

Total returns (share price plus dividends) should average 2% to 5% above the market average.

- Examples (mostly US) include Coca-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, Unilever, Danone and Procter & Gamble.

They offer good protection during recessions – often because of high dividend yields and investor confidence that they will survive.

- Peter Lynch advised always having some stalwarts in your portfolio.

Stalwarts should demonstrate product innovation and not give up market share, take on too much debt or di-worsify.

- They can be used as buy-and hold investments, or bought when valuations are depressed, to await normalisation.

Slow growers

These large firms are typically regulated (often utilities or telecoms).

- Since they typically produce below-average returns, they should be avoided unless there is some special situation attached.

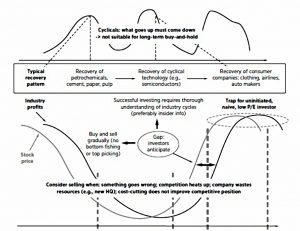

Cyclicals

Buying a cyclical after several years of record earnings and when the P/E ratio has hit a low point is a proven method for losing half your money in a short period of time – Peter Lynch

Cyclicals are sensitive to the business cycle because of elastic demand for their products.

Frederik’s Examples include:

- car manufacturing

- steel

- airlines

- paper and

- chemicals

Their profits rise when the economy does well but drop badly during recessions.

- The market anticipates this volatility by bidding up share prices during downturns (in anticipation of recovery) and dumping them as the economy becomes overheated.

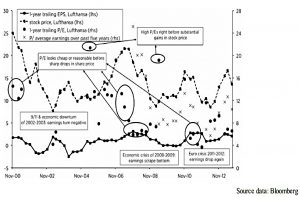

Frederik uses the chart of German airline Lufthansa to illustrate this process

Investing in cyclicals is all about timing.

- They are not safe buy-and-hold investments.

- To be successful you must be earlier than other investors to anticipate the stock price gyrations.

Thus there is an element of speculation which takes the practice outside Frederik’s fairly narrow definition of investment.

- Intrinsic value is not important, and economic considerations are.

Cyclicals are certainly not for everyone, but some investors seem to have the knack of anticipation.

Those top investors who do trade cyclicals offer the following key rule:

Don’t buy at low PE and sell at high PE.

- Buy when earnings are awful, but may improve within the next year.

- Sell when earnings momentum is high but will soon deteriorate.

This means buy at a high trailing P/E and sell at a low trailing P/E.

- This can be seen in the Lufthansa chart – close to price peaks, trailing P/E ratios look reasonable or cheap.

- Around price bottoms, P/E ratios tend to be high.

You can also use normalised earnings (P/Enorm), buying when these are low and selling when they high.

- Enorm is defined by John Neff as “estimated earnings at a more fortuitous point in the business cycle”.

- David Dreman uses average earnings over five years across a business cycle.

This logic is shown on the Lufthansa chart above.

Other suggestions include:

- good knowledge of the industry, so as to anticipate turning points

- Jim Rogers looks at capex relative to depreciation as a leading indicators of supply imbalances – low capex is a positive (lack of supply ahead)

- rising inventories indicate oversupply

- rising wages indicate increased worker power after strong earnings (oversupply ahead)

- building new plants and fancy headquarters indicate a top

- contrarian thinking: buy when everybody else is giving up and brokers say sell; sell when cyclicals are popular and analysts say buy

- don’t try to buy at the bottom or sell at the top – buy on the way down, and sell into strength

- watch for insider buying when earnings are still low

- stick with the safest (biggest) cyclicals

Turnarounds

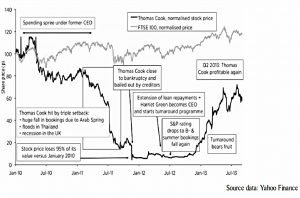

Turnarounds are fallen angels that investors hope will one day recover, potentially in spectacular fashion, and perhaps even within a weak general market.

- Frederick uses the turnaround story of Thomas Cook as an example.

In 2011 the company was hit by a slump in bookings for three reasons.

- Revolutions in Arab countries.

- A flood in Thailand.

- And in the UK, a recession hit discretionary spending.

The CEO left and Thomas Cook almost defaulted on its debt in November.

- By now the stock was down 95%.

- The firm was bailed out by it creditors through increased facilities and extended loans.

By now, holidaymakers were unwilling to book with a firm that might fail.

- Thomas Cook lost market share to TUI.

A new CEO managed to restore market confidence and the stock started to go up.

- By summer 2013, when the stock was in profit again, the share price had rallied more than 1000% over a year (in which the FTSE-100 went up 10%).

So turnarounds can be very rewarding, but investing in them is not easy.

Here, Frederik makes a distinction between turnaround investing and vulture investors, who look for companies that cannot avoid bankruptcy.

- Vultures usually buy debt so as to be first in line when the business emerges from bankruptcy or is liquidated.

Attractive turnarounds

Here are the tips from top investors on how to choose turnarounds:

- Has the company sufficient liquidity?

- Is there a lot of short-term debt that the bank can call in?

- Is there enough cash?

- Does the company have a decent core business (franchise)?

- Is (was) it a market leader?

- Does it throw off a lot of cash?

- Can it expect goodwill from its creditors?

- Does the company have other serious risks, for example customer concentration?

- A major customer switching to a more stable supplier could be fatal.

- Can the company attract the necessary resources (new management and capital)?

- Large companies have an advantage here.

- Does it have a high profile with government (eg. is it a large employer)?

- Is management up to the task?

- Do they have an appropriate track record?

- What is their strategy?

- Will there be anything left for shareholders if the company goes bust?

- How spectacular might the stock price recovery be?

- Is it a bull or bear market?

Perhaps surprisingly. less efficient (profitable) companies (eg. those with high fixed costs) make better turnarounds.

- Since they are riskier they will have been sold off more heavily.

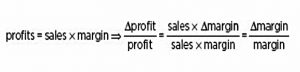

- And a small increase in the profit margin can lead to a large increase in profit:

Existing tax-losses can also give an extra boost to future profits.

Frederik also points out that the possibility of a takeover should be ignored.

- These are unlikely, especially at a decent price, since the acquirer could wait for bankruptcy.

When to buy a turnaround

Signs to look for before buying include:

- No dividend cuts

- Insider buying

- Price of the company’s bonds

- though the bond market will often give the same signal as the stock market

- The market ignores further bad news

- this indicates a bottom in the stock price, as investors look ahead to recovery

- A new CEO with a good track record arrives from a leading company

When to sell a turnaround

There are two possible scenarios:

- The company has solved its problems and everybody can see it.

- The question then becomes whether the company is a good long-term hold.

- If not, since this point is hard to identify exactly, phased selling may be appropriate.

- The company never gets its problems under control.

- Red flags include: debt increasing

- inventories grow faster than sales

- senior management turnover continues for several years.

Turnaround summary

The diagram below summarises the preceding sections:

Asset plays

Asset plays are companies where the value of assets is not reflected in the stock price.

- Historically these were often linked to foreign accounting practices.

Sometimes it is simply the case that the value of the assets is hard to work out.

- This could be real estate in the books at cost, for example.

Or it could be that the value is unlikely to be realised soon (for example, historic tax losses).

To invest in an asset play you need to identify a catalyst for the value to be recognised.

- Sometimes this catalyst will be the investors themselves (activist investors).

Asset plays are another specialist type of investment, and definitely not for everyone.

Conclusions

It’s been another interesting chapter for me, with some clear conclusions:

- Not all types of stock should be traded

- Good choices (depending on your personality) include fast growers and stalwarts

- Cyclicals, turnarounds and asset plays are for specialists

- New companies (not profitable) and slow growers should be avoided

- Different types of stocks need to be traded differently.

- Fast growers are ideal buy-and-hold investments

- Cyclicals can’t be treated this way.

- Stalwarts can be buy-and-hold, but can also be traded from a depressed valuation.

- Turnarounds and asset plays are bought by specialists in anticipation of a specific event.

- Don’t try to be an expert in all these types of stock.

- Fast growers and stalwarts share some commonality in approach.

- The other categories required a degree of specialisation.

- None of the types are easy to trade.

- Most top investors recommend buying and selling gradually, for all types of stock.

More on this and other buying and selling techniques in a few weeks, in our next visit to Excess Returns.

Until next time.