Freakonomics 4 – Names

Today’s post is our fourth visit to a classic book – Freakonomics by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner.

Names

Chapter 6 of the book continues the theme of parenting. by looking at the impact of names on children’s lives.

The authors begin with Robert Lane from Harlem, who in 1958 called one of his sons Winner, and three years later, called another Loser.

- Loser (known as Lou) was a success, graduated and became a detective sergeant in the NYPD.

- Winner has “nearly three dozen arrests for burglary, domestic violence, trespassing, resisting arrest.”

For once, the opposite of nominative determinism. For the flip side, we have a woman named Temptress:

[She] was charged with ungovernable behavior, which included bringing men into the home while the mother was at work. Temptress didn’t have ideal parents. Not only was her mother willing to name her Temptress in the first place, but she wasn’t smart enough to know what that word even meant.

Unusual names

Unusual names are more common in black culture.

- To dig into this phemomenon, the authors rely on the work of Roland G. Fryer Jr., a young black economist famous for studying the “acting white” phenomenon and the black-white test score gap.

Fryer says:

I basically want to figure out where blacks went wrong, and I want to devote my life to this.”

One notable difference is culture – black people don’t watch the same TV or smoke the same cigarettes.

Fryer came to wonder: is distinctive black culture a cause of the economic disparity between blacks and whites or merely a reflection of it?

Fryer looked at birth certificate data for every child born in California since 1960 (16M+ children).

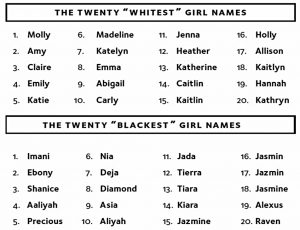

Until the early 1970s, there was a great overlap between black and white names. By 1980 [the typical black girl] received a name that was twenty times more common among blacks.

The same thing happened with boys, but to a lesser extent.

The most likely cause of the explosion in distinctively black names was the Black Power movement, which sought to accentuate African culture and fight claims of black inferiority.

At the time the book was written, many black names were unique to blacks:

More than 40 percent of the black girls born in California in a given year receive a name that not one of the roughly 100,000 baby white girls received that year. Even more remarkably, nearly 30 percent of the black girls are given a name that is unique among the names of every baby, white and black, born that year in California.

There were also 228 babies named Unique during the 1990s alone, and 1 each of Uneek, Uneque, and Uneqqee.

Fryer looked at the parents of these babies with unusual names:

An unmarried, low-income, undereducated teenage mother from a black neighborhood who has a distinctively black name herself [was most likely to choose a distinctive black name]. In Fryer’s view, giving a child a superblack name [means a mother is] “acting black.”

White mothers send a similar signal.

Studies show that resumes with black names lead to fewer job interviews than do those with white names.

[But] they can’t explain why DeShawn didn’t get the call. Was he rejected because the employer is a racist and is convinced that DeShawn Williams is black? Or did he reject him because “DeShawn” sounds like someone from a low-income, low-education family?

Because the audit studies can’t measure the actual life outcomes of the fictitious DeShawn Williams versus Jake Williams, they can’t assess the broader impact of a distinctively black name. Maybe DeShawn should just change his name.

Fryer looked into this using the California data, which included:

Information about the mother’s level of education, income, and, most significantly, her own date of birth. This made it possible to track the life outcome of any individual woman [mother].

Using regression analysis to control for other factors that might influence life trajectories, it was possible to measure the impact of a single factor – in this case, a woman’s first name – on her educational, income, and health outcomes.

Fryer compared the life outcomes of mothers with distinctively black names with those of mothers without them.

On average, a person with a distinctively black name does have a worse life outcome than a woman named Molly or a man named Jake. But it isn’t the fault of their names. The kind of parents who name their son Jake don’t tend to live in the same neighborhoods or share economic circumstances with the kind of parents who name their son DeShawn.

And that’s why, on average, a boy named Jake will tend to earn more money and get more education than a boy named DeShawn. His name is an indicator – not a cause – of his outcome.

So what about those who change their names?

Anybody who bothers to change his name in the name of economic success is at least highly motivated, and motivation is probably a stronger indicator of success than, well, a name.

Income and education

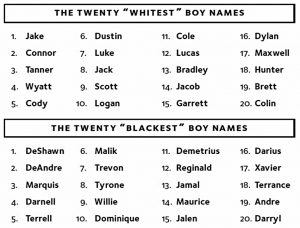

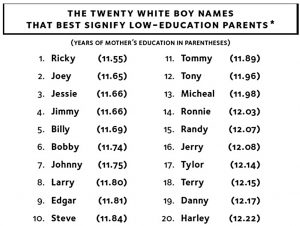

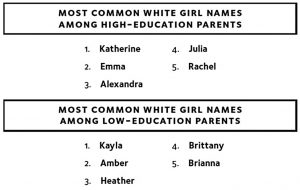

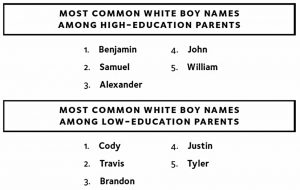

Next, Fryer looked at patterns in names.

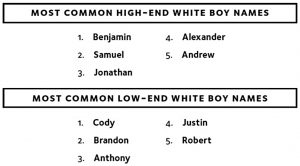

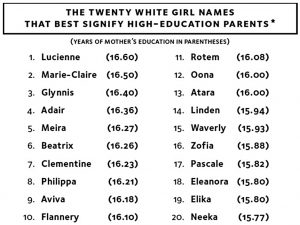

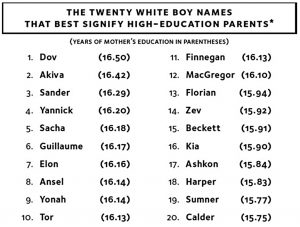

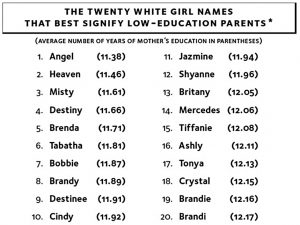

Among the most interesting revelations in the data is the correlation between a baby’s name and the parents’ socioeconomic status.

Considering the relationship between income and names, it is not surprising to find a similarly strong link between the parents’ level of education and the name they give their baby.

Names through time

Next, Fryer looked at patterns of names through time.

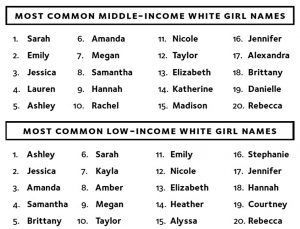

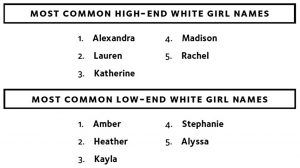

There is a clear pattern at play: once a name catches on among high-income, highly educated parents, it starts working its way down the socioeconomic ladder. Amber and Heather started out as high-end names, as did Stephanie and Brittany.

It isn’t famous people who drive the name game. It is the family just a few blocks over, the one with the bigger house and newer car.

Parents are reluctant to poach a name from someone too near – family members or close friends – but many parents, whether they realize it or not, like the sound of names that sound “successful. But as a high-end name is adopted en masse, high-end parents begin to abandon it.

The authors also note that many girls’ names (Shirley, Carol, Leslie, Hilary, Renee, Stacy, and Tracy) were originally boys’ names.

- There is no traffic in the opposite direction.

What the California names data suggest is that an overwhelming number of parents use a name to signal their own expectations of how successful their children will be. The name isn’t likely to make a shard of difference.

Conclusions

The rest of the book is padded out with magazine profiles, reprinted newspaper columns and a Q&A with the authors.

- This is all entertaining but doesn’t add much to what has gone before.

Which is why this article is a bit shorter than I expected.

There is a common thread running through the everyday application of Freakonomics. It has to do with thinking sensibly about how people behave in the real world. You might become more skeptical of the conventional wisdom; you may begin looking for hints as to how things aren’t quite what they seem.

Some of these ideas might make you uncomfortable, even unpopular. But Freakonomics-style thinking doesn’t traffic in morality. If morality represents an ideal world, then economics represents the actual world.

And so we’ve reached the end of the book.

- It’s been an entertaining ride, and even though I had read the book before, an educational one.

I’ll be back in a few weeks with a summary of the four articles.

- Until next time.