Smart Portfolios 3 – Finding the Best

Today’s post is our third visit to Rob Carver’s book Smart Portfolios.

Contents

Risk appetites

Chapter Four of Rob’s book describes some “simple, smart and safe” methods to find the best portfolio (ignoring costs).

- He starts by looking at different levels of risk appetite.

We have a Risk Tolerance Questionnaire if you’d like to find out yours.

- Alternatively, a good rule of thumb is to assume that equities will fall by 40% (at least) once in your investing lifetime.

If you know how much you would be able to let your portfolio fall without selling, you know what your ceiling on equities (the most volatile asset class) is.

- For example, if you could tolerate a 20% loss, you can’t have more than 50% in equities.

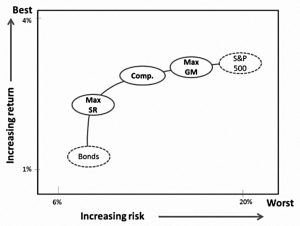

Rob begins by assuming that everyone is after one of three portfolios:

- max geometric return

- this would be something like 80% equities / 20% bonds

- it returns 3.0% real with 16% volatility for an SR of 0.19

- max SR

- this is 32% equities, 68% bonds

- it should return 2.3% real with 8.7% volatility for am R of 0.266

- compromise

- this is anything between the other two – Rob goes for the classic 60% equities, 40% bonds

- my own (target) retirement portfolio is 75% equities, 25% cash / bonds / alternatives

- Rob’s 60/40 portfolio should return 2.9% real with 12.5% volatility, for an SR of 0.229

Investor types

Rob has three portfolios but identifies five types of investor.

For the very low-risk investors, even the max SR portfolio is too racy.

- Rob recommends putting some money in the max SR and keeping the rest in cash.

The low-risk investor uses the max SR portfolio to return 2.3% with a volatility of 8.7%.

- The medium risk investor uses the 60/40 compromise portfolio.

- The high-risk investor uses the max return portfolio (80/20 rather than all equity).

The Borrower should leverage the max SR portfolio.

- Rob assumes a real interest rate of zero but says that the maths makes sense up to a real rate of 0.75%.

I have my doubts that such rates are readily available to the typical private investor.

- My focus is on the medium and high-risk investors.

That is not to say that I will never incidentally use leverage (for example via spread bets or options).

Safe assets

In the next section, Rob introduces a bond with a quarter of the risk of the original bond (and therefore a higher SR, even with lower returns).

- This safe bond is useful to the ultra-safe investor, and also to the Borrower.

But the lower returns mean that investors in the Max SR, compromise or Max Return portfolios should avoid it.

If you match the return of the max SR portfolio then the volatility is higher.

- If you match the volatility, then the return is lower.

Rob recommends that investors avoid low-risk (low-return) assets.

- For example, he prefers long maturity bonds (at least five years) to short ones.

- He would also add corporate and emerging market bonds to a government bond allocation.

Risk weighting

The next section looks at risk weighting.

Rob starts by normalising returns for all assets to a constant standard deviation (without changing SRs).

- This calculation is not always straightforward but Rob’s handcrafting method (explained below) means that you don’t need to do the calculations.

This leads to an example portfolio with equal geometric means, equal standard deviations and identical correlations.

- We know that the optimisation process for such a portfolio will lead to equal weights.

Rob then converts the risk weights back to cash weights.

- When correlations aren’t too high, risk weighting leads to similar weights to those produced by optimising cash weights.

But risk weighting is better when correlations are high.

Handcrafting

Rob uses a simpler, top-down method that he calls handcrafting.

The sequence of allocations is (for equities): asset, country, industry, stock.

- Other assets might have different categories below the top level.

You also need to decide on implementation (eg. ETFs vs stocks) to optimise the trade-off between diversification and cost.

Rob illustrates the hand-crafting process using a portfolio of US bonds, UK stocks and US stocks.

- group similar assets

- these have higher correlations

- this gives us a stock group and a bond group

- equally weight the groups

- we have 50% bonds and 50% stocks

- allocate equally within groups

- in Rob’s example, we now have 50% US bonds, 25% UK stocks, 25% US stocks

These are risk weightings, which would need to be converted back to cash weightings.

If group sizes are radically different, larger groups should be over-weighted.

- There is a similar problem if correlations within the different groups vary widely.

Rob promises a fix later in the book.

Risk Parity

Rob’s method produces volatility parity allocations, which are close to those used by risk parity funds.

- Risk parity funds also account for internal diversification within each asset class, to make sure that the amount of risk coming from each asset class is the same.

They are also leveraged to compensate for the low risk / low return that comes with a high bond allocation.

Higher risk portfolios

The drawback (for me) is that the hand-crafting method creates the max SR portfolio (assuming equal correlations within a group).

- At this point, I don’t know how to derive the max return portfolio.

Max SR portfolios don’t have high enough returns for me.

What I need to discover is how the hand-crafting method applies to the compromise and max return portfolios.

So far all I know is that hand-crafting supports top-down constraints, so I could set a maximum bond allocation of 20%, for example.

- Which is pretty much my current approach to asset allocation.

In the next section, Rob confirms that this is the way to go.

- Split assets into low-risk and high-risk top-level groups

- I prefer an Equities / Bonds / Alternatives split, which is not too different

- Set a (risk) weight to the lowest risk group.

- Rob suggests a 10% risk weighting for the max return portfolio, which should translate into a 20% cash weight.

- For the compromise portfolio, you could go as high as 30% risk to the low-risk asset.

And there’s more to come on this topic in a later chapter.

Embarrassment

Rob tries to reassure readers that – for developed markets at least – the hand-crafting process won’t expose them to massive embarrassment on the basis of large deviations from market cap.

- For example, the US is 94% of the North America group, but hand-crafting would have you allocate 50/50 with Canada.

All methods of allocation (equal, handcraft, market cap) produce similar results across 22 developed markets and all easily beat a formally optimised portfolio.

- That said, I’m unlikely in practice to allocate equally to the US and Canada.

I’m more likely to ignore Canada entirely, by using a cheap S&P 500 ETF.

- The best I might do for Canada is to use a North American ETF instead.

Unpredictable risk

Rob admits that some kinds of assets include less predictable risk (he calls it “risky risk”) that isn’t captured by the standard deviation.

- He includes emerging markets and tech (including biotech) here, along with junk bonds.

The issue is that they have sudden spikes in volatility and more steep price falls than would be expected.

Formally this is described as having negative skew, and high kurtosis (fat tails).

- Rob’s solution is to under-weight to these kinds of assets.

Be flexible

Rob stresses that there is no “correct” hand-crafting solution.

- Every investor should come up with their own groups and weightings.

Handcrafting is a process rather than a blueprint.

Conclusions

It’s been another interesting section of the book, but I must admit to a slight feeling of disappointment at the end of it.

- The “systematic” hand-crafting process leads directly to the max SR portfolio.

The returns from this portfolio are too low for my purposes, and to produce the max returns portfolio that I am after requires a fair amount of top-down human judgement.

- I have no issue with this in principle, but in practice, it brings the asset allocation process back towards the one I have been using for almost three decades.

So the 134 (dense) pages I have covered so far leave me pretty much where I started.

- But there’s a lot more of the book to get through.

Until next time.