Smart Portfolios 7 – Predicting Returns

Today’s post is our seventh visit to Rob Carver’s book Smart Portfolios.

Contents

Prediction

In Part Three of his book, Rob abandons the idea that risk-adjusted returns can’t be forecasted.

- His experience working in hedge funds leads him to believe that simple trading models can have some success in predicting future returns.

Which is not the same as believing in special individuals with the ability to see into the future without models.

Rob notes that markets can always move still higher (or lower) and that even if you know that something is likely, working out exactly when it will happen is hard.

- You also need to be better at predicting the future than other people are.

Models

Rob sticks to two simple models – momentum/trend-following and dividend yield (a special case of the value factor).

- Both factors work for bonds as well as stocks.

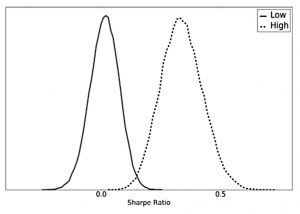

The chart shows the distribution of SRs for high and low momentum strategies.

- It’s very likely that high momentum works.

Rob’s approach to implementing these models is different from mine.

- Rob uses forecasts to change the asset weights in his main (“passive”) portfolio.

A more extreme version of this approach is to exclude certain assets (with low expected returns) entirely.

- Rob also likes to use selection at the last stage of the allocation process – to select the shares in each sector that are most likely to outperform, for example.

I would prefer to use these techniques in a separate, actively-managed portfolio.

- This would make it easier to track its returns, and in turn, help me to decide each year how much capital should be allocated to this approach.

One of my goals for 2019 is to move closer to a systematic approach to investing.

- Doing this would make it easier to adopt Rob’s approach, and I suspect he is a long way down that track in his personal portfolio.

Momentum

Rob uses the returns from the last 12 months (ideally including dividends) to work out a trailing SR using estimated/fixed volatilities.

- From this, he derives a weighting adjustment (to his existing position).

Since the adjusted weights won’t add up to 100%, you then have to normalise the weights within the portfolio.

You can use an absolute or relative approach.

- In relative momentum, you stay fully invested (in say bonds and equities) but allocate more to the asset which has been doing well.

In absolute momentum, you don’t want to assets that are going down in price, so you could be underweight both bonds and equities at the same time.

- When the sum of the adjusted weights is less than 100%, you hold the remainder in cash (rather than normalising up to 100%).

Yield

Yields are a nice, easy to measure proxy for value (cheapness).

- Rob says that earnings yield and carry – yield above the short-term risk-free rate – work just as well.

The process is the same as for momentum:

- Convert the yields to SRs

- Work out the difference from the median SR yield

- Look up the adjustment factor in the table Rob provides.

Adjusting a portfolio

Rob provides a long and detailed section on how to adjust a hand-crafted multi-level portfolio using these processes.

- I don’t intend to use this method, so I’m afraid that those who do will need to look it up in the book.

Rob notes that yield (and value in general) work best when assets are similar, and therefore their prices rarely drift apart for long.

- When assets are very different, relative valuations are less important, and momentum is more likely to be successful.

At the top of the portfolio pyramid, momentum is king, but at the bottom, the yield will rule.

Rob likes relative momentum for asset allocation.

- Absolute momentum reduces mean returns, and yield works better lower down the tree.

This makes sense since the main point of the asset allocation process is to put money into dissimilar assets.

If you want to use both models (or any two models) together, you use the geometric means of the individual adjustment factors (eg. equity momentum and equity yield adjustments).

- In a multi-level model, you repeat the process at each level, starting with the top.

Active management

There are two problems with active management:

- A lot of it isn’t very active

- Many funds are closet trackers, so you need to look at the active share of the fund

- It’s expensive

- Not only are the funds more expensive (in terms of base fees and trading costs) than trackers and ETFs, but

- The platforms on which you hold them (particularly for OEICs) tend to charge more (and particularly for large portfolios)

To work out whether an active fund is worth investing in, you need to compare it to a suitable passive tracker.

Rob imagines two funds with 10-year track records:

- 10% average gross returns, 2% charges, 8% net

- 7% gross, 1% charges, 6% net

Using a correlation between managers of 0.85 (typical if the funds have similar styles), Rob works out that there is a 78% chance that future outperformance will be enough to cancel out the 1% extra in fees.

- Rob would like to see at least a 90% chance.

To get to 90%, you would need a 4.3% pa gross return advantage over 10 years.

You also need to account for volatility, or a riskier fund may seem to do better.

- You also need the correlation between the funds (from monthly returns) – if you don’t have this, use 0.85.

Rob provides a table of hurdles for the active fund to clear, based on correlation and length of track record.

Rob then uses Fundsmith as an example, comparing it to IGWD.

- Fundsmith has returned 12.4% pa over the last five years compared with 10.7% for the ETF.

The outperformance is barely a quarter of the 6.4% pa required.

- Buffett, on the other hand, has beaten the S&P 500 by 12% pa over 50 years.

Luck

Rob also mentions the “infinite number of monkeys” problem, formally known as the multiple testing problem.

- Some funds will pass the 90% hurdle simply by luck.

Since you need several decades of data to demonstrate a manager’s outperformance, and their career will be almost over by then, Rob prefers to look at how a manager makes investment decisions and manages risk, rather than analyse their track record.

- Since retail investors are unlikely to have access or the skills to do this properly, he recommends that they steer clear of active managers.

I wouldn’t go that far, but I tend to use active funds (ITs, actually) to access difficult and/or illiquid assets.

- Or to back conviction managers whose allocations will be far from any benchmark tracked by a regular market cap ETF.

Once again, I’m looking for lack of correlation rather than guaranteed outperformance.

Smart-beta

We know from our handcrafted portfolio design that Rob doesn’t like market cap weighting (dumb beta).

- He prefers equal weighting for similar assets, and

- Volatility weighting across asset classes.

Factor funds (smart beta – momentum, value etc) should have better returns, but they haven’t been around long enough for statistically significant proof of this.

The snag is that smart beta costs more.

- So Rob has calculated the maximum extra fees that you should pay:

In general, only momentum funds are cheap enough to be used with large-cap firms.

- With small-cap, any strategy is fine.

One again, my small allocation to smart beta is there for its non-perfect correlation as much as for outperformance.

Robo advisors

7 Circles have a long series of articles on robo advisors.

- Whilst there are some nice apps and websites around, most approaches are simplistic (Robos like Scalable Capital and Exo Investing are exceptions) and the charges are too high.

Fees typically work out at a minimum of 0.3% to 0.5% pa on top of the ETF charges (( There are a couple of exceptions – see our table here – but then again, many charge much more ))

- For all but the smallest portfolios, manual rebalancing (the main value add of robos) will be cheaper.

Rob notes (as I have) that robos market themselves using comparisons to the most expensive platforms and advisors.

- If they referred to a simple DIY approach using ETFs they wouldn’t look so attractive.

Conclusions

Since I plan to run my active strategies in a standalone portfolio, rather than by adjusting the allocations to my passive funds, there has been less of a takeaway for me personally today.

- But I enjoyed the tests of how much an active manager needs to outperform by, and the evidence that factors and some types of smart beta does work.

I also share Rob’s scepticism about Robos as they currently exist.

- But I retain a small amount of hope that their potential might one day be realised by a player with scale. (( Vanguard, Fidelity, or – in the light of the Marcus savings account – perhaps Goldman Sachs ))

Until next time.