Budget 2018

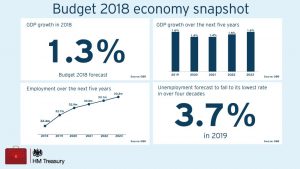

Today’s post takes a look at the unusual level of speculation in advance of the Chancellor’s Budget 2018, and at what actually happened.

Contents

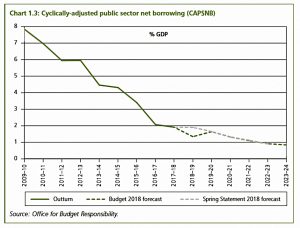

An end to austerity

All the talk in the run-up to the Budget has been about “an end to austerity”, as stated by Theresa May at this year’s Tory party conference.

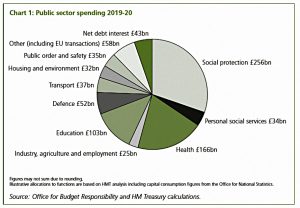

This has been interpreted as meaning that more money will be found for popular projects like the NHS (£20 bn by 2023 for the health service) and building more houses.

- Other issues include the rollout of Universal Credit and social care cost shortfalls.

Chancellor Hammond said as much to the BBC:

We will have to find a little more, each of us, to… expand our NHS to meet the needs of an ageing population.

I will always do everything I can to minimise the necessity for any increases in taxation, and to keep the burden of taxes as low as I possibly can.

Which in turn begs the question of where this money will come from.

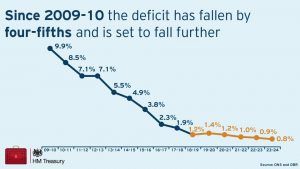

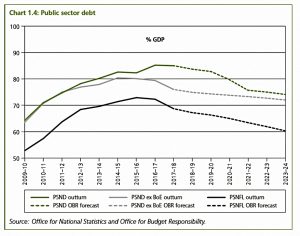

In truth austerity is likely return in the long run, since the UK has relatively few state assets, yet a large public debt and massive of future pension liabilities.

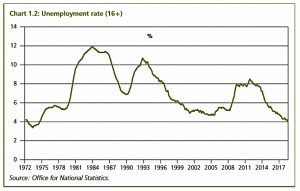

- Demographics mean that the pensioner to worker ratio will continue to rise.

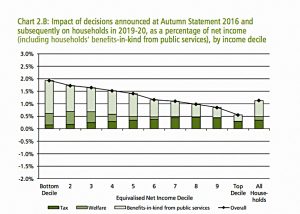

Taxation will have to rise, and this may be the budget which begins the process.

- And of course, tax rises make people poorer even as increased spending suggests that austerity is over.

We also mustn’t forget a potential shock to the UK economy from Brexit, now just five months away.

- The Chancellor would probably like to keep some powder dry for any reaction to that.

But political concerns (Tory weakness leading to a post-Brexit election and a Corbyn government) probably ruled out a “wait and see” budget.

- And manifesto commitments to reducing the deficit and the national debt in the medium term mean that not too much can be done through issuing more debt.

So the vast majority of pre-budget speculation this year has revolved around potential tax reforms (for which, read increases).

- This could be more popular than it sounds – 60% now favour higher taxes (and spending) compared to only 31% in 2010.

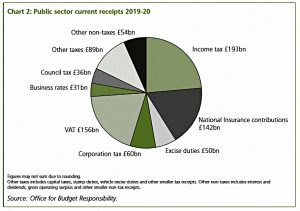

At the same time, we are already close to the post-war highs in terms of UK tax raising.

- A 1% increase would take us to a new record.

What had been ruled out

Not too much, as it happened.

The government had confirmed that:

- the triple lock on the State Pension would continue

- the LISA would be preserved

- there would be a freeze on fuel duty

Tax increases

We’ll work through all of the things that might have happened, though of course most of them didn’t.

- It can be illuminating to see how people other than the Chancellor are thinking about potential future tax rises.

Income tax, NIC and VAT are protected within the manifesto.

- But polls had shown that many people would be happy to pay 1% on income tax if it was directed to the NHS.

- And VAT could have been extended to currently exempted goods (like food).

- Or the VAT threshold could have been reduced from the existing £85K pa.

The Employment Allowance that rebates the first £3K of employer’s NICs for each company was also thought to be under threat.

- This might not have been a cut in the allowance, but instead a restriction of the rebate to the smallest companies.

- And indeed, this happened – only companies paying less than £100K in NICs will qualify.

Another potential NIC change would be to add NICs to salaries earned by those above the State Pension Age.

- But the government has always said that it makes no sense for pensioners to be paying into a pot that they are eligible to draw from.

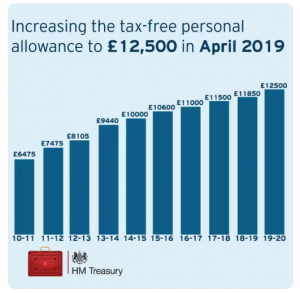

A freeze on income tax allowances was possible, but another manifesto commitment set 2020 targets for these (£12.5K and £50K).

- In fact the manifesto commitments were brought forward by a year, to April 2019.

Increasing the burden on the “rich” is always popular, but in fact income inequality has fallen since 2008 and it’s already the case that 50% of income tax comes from just 3% of workers.

- A quarter of income tax comes from just 0.6% of adults.

And these are the people who can most easily work less, or work abroad.

The same applies to corporations, which meant that increases to Corporation Tax were unlikely.

- But some kind on of online sales tax had been mooted, to defend high streets against Amazon.

- And we got one, though it’s been deferred by a year to wait for OECD proposals which might replace it.

There had been talk that the dividend allowance – cut last year from £5K to £2K – might be cut again (or scrapped).

Some industry figures had also suggested that EIS reliefs might be under threat, but this sort of rumour emerges ever year, largely to drum up extra business under the banner of “while stocks last”.

Others thought that a new Care ISA could be introduced to encourage people to save in order to fund their own social care.

- The problem here is that take up would likely depend on the government publishing a cap on personal contributions to care costs, something that it has shield away from for the last five years.

A new stamp duty surcharge for foreign property buyers had also been discussed.

- This seemed unlikely with Brexit looming.

- But there will be a consultation on this.

And a tax on single-use plastics was expected.

A final suggestion had been extra bands of council tax.

- But most of that goes to local rather than central government, so it was unlikely to have been a priority for Hammond.

Capital gains tax

Entrepreneurs’ relief is a low rate of capital gains tax (CGT) on the first £10M in profits from the sale of stakes in growing companies.

- Some predicted this might be hit.

- In fact, all that happened was that the qualifying period was doubled to two years.

More aggressive would have been the removal of CGT forgiveness on death.

- When assets are inherited, they are deemed to have been passed on at the prevailing market value, effectively re-setting the clock on CGT.

An outside shot was an increase in the top rate of CGT (currently 20%).

- Doubling it to match the higher rate income tax could not be ruled out.

And some commentators thought that we might see a temporary CGT amnesty for buy-to-let landlords looking to exit the sector.

- The exemption (from a special high CGT rate of 28%) might have been linked to sales to existing tenants, and the benefit could have been split between the landlord and the tenant.

Pensions

Hammond said in a recent speech (at an IMF jamboree in Bali) that pension tax reliefs are “eye wateringly expensive.”

Most observers interpreted this as a signal they would be hit.

- The most popular prediction was a cut in the annual contribution allowance from £40K to £30K (or even £20K).

Less likely was a flat relief rate of 20% or 25%.

- This would mean that higher-rate taxpayers would be taxed twice on their pensions, and might sound the death knell for the best savings vehicle that we have.

The government has also said that:

No consensus for either incremental or more radical reform of pensions tax relief has emerged since the consultation in 2015.

Somewhere in the middle in terms of probability was yet another cut to the Lifetime Allowance.

- I personally thought this was not likely, since the LTA is now an indexed allowance.

- And indeed, at £1.05M from next year, low annuity rates mean that the LTA now only supports an annual income of around £25K (indexed from aged 55).

More likely was a reduction in the threshold for the higher earners taper on the pension contributions allowance.

- Those on more than £150K lose £1 of allowance for every £3 earned, down to a £10K allowance.

- A cut of the threshold to £125K was mooted, as was a hard cap of no contributions for those on high wages, or a steeper withdrawal slope (eg. £2 for every £3 earned).

Hargreaves Lansdown even suggested a transaction tax within pension funds only.

The perennial threat to the 25% tax-free allowance surfaced again – perhaps as a limit to the size of eligible lump sum.

- Surely this could not be introduced retrospectively (ie. on funds already inside pensions).

- It would need to be introduced slowly and progressively – which means that it couldn’t raise much money in the short-term.

And further reductions in the annual allowance for those already in receipt of their pension (the MPAA – down last year from £10K to £4K pa) had been mentioned.

For defined benefit pension holders, the DB multiplier by which their pensions are assessed against the LTA might have been increased from the historic 20x to something closer to the neutral 31x.

Inheritance tax

Inheritance tax (IHT) is the most hated of all taxes – people want to pass on money to their family when they die, and IHT is seen as double taxation.

- So is VAT, but people struggle to see dying as spending money.

- And even if IHT were to be abolished, the VAT would be collected when the money was finally spent by the heirs.

IHT is also seen as complicated by most commentators, though it doesn’t seem that way to me:

- you have a £325K allowance

- plus another £125K (rising to £175K in 2020) if you pass a property to your child – the “residence nil-rate band” (RNRB)

- pensions also escape IHT, though they are subject to income tax (on the heir) if you die after age 75

The other key relief is business property relief (BPR) which applies to farms, forests and AIM stocks.

- And you can put assets in trust to avoid IHT (but pick up other taxes instead).

Everything else is taxed at a hefty 40%, which means that people try quite hard to avoid paying IHT.

- The only alternative is to give away your money during your lifetime.

- Which is tricky, since you don’t know the date of your death.

Since the base allowance has lagged behind inflation, IHT has become a nice little earner, raising £5.2 bn in 2017/18.

- So any reforms were likely to be fiscally neutral.

Hammond could have scrapped the RNRB, though it’s only been around for a couple of years.

- A better option would be to merge it with the general allowance – this would be fairer to those without children.

A more radical option would have been to reduce the general allowance (to say £100K) and cut the tax rate to something people couldn’t be bothered to avoid – 5% has been suggested.

And while BPR could have been reformed, the most obvious target (AIM) had been announced as safe from reform before the Budget speech.

Changes to the gifting allowance were also mooted – the annual allowance has been stuck at £3K for some time (32 years).

- Perhaps the many small gifting allowances could have been pooled into a single £10K annual allowance.

Maybe bringing pensions back within the scope of IHT would have been the simplest thing to do.

Alongside IHT, the massive hikes to probate fees (from £215 to £20K for estates over £2M) – which were shelved when Brexit negotiations began – could have been brought back.

Conclusions

After all the speculation, that’s a pretty bland budget.

- I think that’s because the government has more money than it predicted.

- So it can give money away without raising taxes much.

There were none of the widely discussed changes to pensions, capital gains or inheritance tax.

The personal allowance and basic rate tax increases are welcome.

- And there wasn’t much in the way of bad news for investors.

My reactions can mostly be lifted from this week’s leader in the Spectator:

- Hammond doesn’t seem to have an ideology

- Even Osborne was committed to rolling back Gordon Brown’s huge expansion of the state.

- Increasing spending is a strange policy for a Tory government.

- There’s not much in the way of preparation for the next inevitable recession.

- The plans announced today might have to be reconsidered in the light of a no-deal Brexit.

- There was no mention of what these changes might be.

But things could definitely have been worse.

Until next time.