Fixing UK Tax

Today’s post looks at a couple of recent articles from Dan Neidle on how to fix the UK tax system.

Dan Neidle

Dan runs a site called taxpolicy.org.uk and we’ve looked at his work before.

- On 1st Jan he published an article in the Sunday Times called “5 ways to fix the UK tax system”, and a few days later he published a follow-up article on his blog.

The main article actually covers six taxes in four areas and also touches on a number of benefits and allowances.

Marginal rates

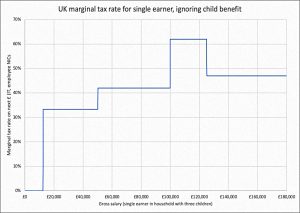

The first issue was marginal tax rates, which sometimes exceed the top rate of 45% for income tax (plus 2% for national insurance).

- Marginal rates matter because they determine your incentive to go out and earn more.

The personal tax-free allowance is eroded at the rate of £1 per £2 earned from an income level of £100K (up to about £125K).

- This makes the marginal rate of income tax and NICs 62% between these two levels (before falling back to 47%).

I have no children and (perhaps because of that) I’m not a fan of child benefits.

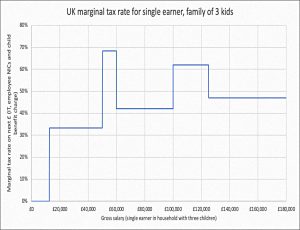

- But Dan notes that things are even more complicated for those with children.

Child benefits starts to be withdrawn at £50,000 – resulting in a marginal rate of 68% between £50k and £60k.

There is also £2K per child of free childcare, which is withdrawn when either parent earns £100K.

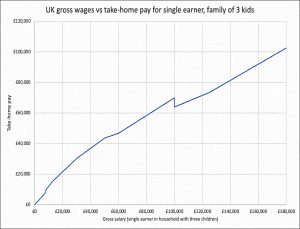

Well, if you’re claiming tax-free childcare for three children, and currently earn £99,999, your take-home pay is £69,884. Earn £1 more, and your take-home pay is less – £63,942. That’s an infinite marginal tax rate.

Since you can’t show an infinite rate, Dan switches to a take-home vs. gross chart.

- You need to earn another £20K to earn back the lost childcare.

These marginal rates have impacts:

People who can control their hours usually think very carefully before putting themselves in the £50-£60,000 bracket, or the £100-£125k bracket. If they’re employed, they often make additional pension contributions. If they’re self-employed they often just stop working for the year.

There’s a similar impact from the withdrawal of benefits, which delivers an incentive not to work.

Dan would remove these marginal rates, and increase higher tax rates (he doesn’t specify whether he means just the 45% rate, or also the 40% rate) to compensate.

- It’s hard to argue with this suggestion.

VAT

There’s a similar cliff edge with VAT.

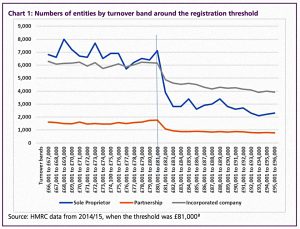

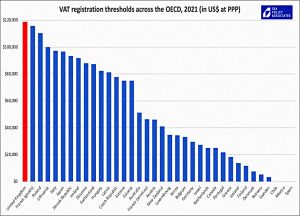

- You only need to register when your turnover hits £85K. (( The threshold was a bit lower when the data used to produce the chart was collected ))

Businesses whose revenue hits the threshold suddenly have to charge VAT, meaning that – overnight – they must either raise prices or lose profits by up to 20%.

This doesn’t matter so much for businesses that sell to other firms (B2B) as their customers can deduct the VAT they pay from that they in turn charge on their sales.

- But it’s a problem for those who sell to the public (B2C).

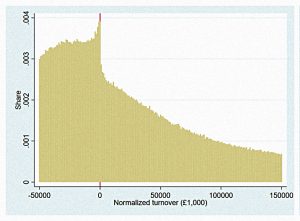

The drop in the number of businesses just above the threshold suggests that companies suppress their turnover as it approaches £85K.

- The danger is that some of these firms might have eventually grown a lot, but we will never find out.

Could this be part of the productivity puzzle? The effect of staying below the threshold is that businesses never grow past one employee… but there is good evidence that businesses with more employees are more productive.

In a follow-up post, Dan went into more detail on the VAT problem.

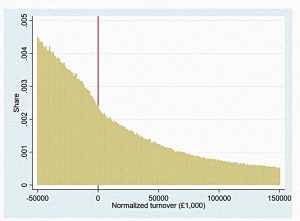

Comparing growing to shrinking firms shows an artificial break in the distribution around the VAT threshold for growing firms, but a natural curve for shrinking companies.

The smooth shrinkage curves also suggests that the growth cliff-edge is real, and not being driven by failure to declare turnover (i.e. criminal tax evasion).

If tax evasion were the cause, you would expect to see a break in the shrinking curve as those close to the threshold fail to declare revenue.

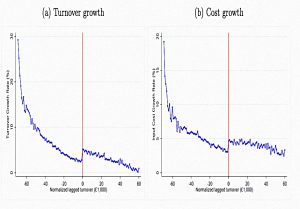

There are similar breaks in the turnover and cost growth curves.

The fact it happens to cost as well as turnover again suggests the effect is real (you can’t keep costs off the books without conspiring with your supplier ).

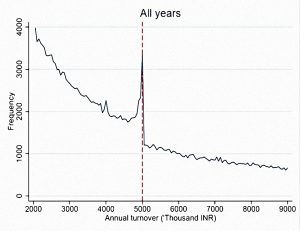

And Dan notes similar breaks in the data from Thailand (above) and India (below).

The first potential fix is to raise the threshold, but this just moves the problem higher up the scale.

- The second is to lower it (the UK threshold is the highest in the world, and the average threshold internationally is £30K), but this would need to be done very carefully, or a lot of firms in the £30K to £80K range will cease trading.

Since the threshold now appears to be frozen at £85K, and inflation is high, a watered-down version of this is what is currently happening.

- Dan calculates that one year of 10% inflation followed by ten years of 4% inflation would shrink the real threshold to £52K by 2034.

Dan’s preferred fix is to start with a 1% VAT rate at £30K and to raise it slowly to 20% at £140K.

- It’s a nice idea, but implementation for small firms would be a nightmare.

Dan admits that HMRC would need to provide free software/apps to make it work and that it would take years to implement.

- An alternative would be to simply lower the threshold and they provide tapering annual rebates to those near the bottom of the scale.

This would make VAT calculations simpler, but introduce a potential cashflow problem for smaller businesses.

- This is probably the “cleanest dirty shirt”.

Land tax

There are three taxes here:

- council tax

- business rates, and

- stamp duty

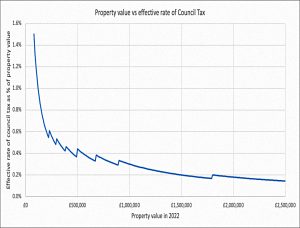

The chart shows the average council tax as a percentage of the property value.

- I think this is a bit misleading, because UK house prices are so high, particularly in London.

If council tax was marketed as a property tax, you could perhaps defend a flat charge of say 0.5% pa.

- But in lots of streets, that would take council tax up to £10K a year.

And since council tax is perceived as a fee for council services, that kind of charge wouldn’t fly.

- All I get for my £2K is my bins emptied once a week (ie. £40 a visit).

You also have the problem of house-rich, cash-poor old people finding the money (the cash flow) to pay for this.

Dan’s second point is that council tax is based on 1991 valuations, and the property market has changed a lot since then.

- This is true but revaluing every property in the UK would be non-trivial unless we plan to take the Rightmove price at face value.

Dan also doesn’t like business rates, but not because it’s an unfair tax on firms.

Most of the economic burden of business rates falls on landlords (because rents are lower than they would be if business rates didn’t exist).

There’s an issue with out-of-date rentable values (as with council tax).

- And the rentable value goes up when a property is improved, which is a disincentive to invest.

Stamp duty is bad because it discourages transactions.

- It would cost me upwards of six figures in tax to move home, which means that I’m staying put unless my dream property comes up (and it costs £100K+ less than my current house).

Since many people need to move houses to take certain jobs, stamp duty also impacts the labour market.

Dan’s fix is to replace all three with a land value tax.

- This would be based on unimproved value, so it wouldn’t deter investment.

But you have the council tax problem that people in London terraced houses would be paying £10K pa to live there.

- So I’m not in favour of a land tax unless it has an annual cap in the £2K area.

Corporation tax

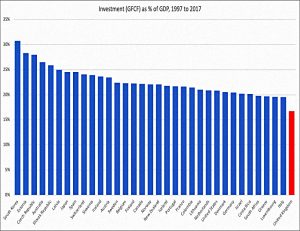

The chart shows that the UK had the lowest ratio of investment to GDP in the OECD (from 1997 to 2017).

- Some of this will be down to the UK’s high proportion of services (which attract less investment) but the difference is striking.

UK tax relief for investment exhibits the two deadly sins of tax policy: it’s really complicated, and it changes all the time. You can’t be sure you’ll qualify, and you certainly can’t be sure the rules will be the same when your investment actually comes to fruition.

Which does nothing to incentivise investment.

Dan suggests giving relief on all investments and increasing the rate of corporation tax to make the move revenue-neutral.

This isn’t my invention – it’s called “full expensing” and it’s supported by the CBI and economists across the political spectrum.

Sound fine to me.

That’s it for today.

- It was an interesting article, and it at least mentioned a couple of my top 5 problems with the UK tax system (marginal rates and stamp duty).

For the record, my other three are the LTA, IR35 and inheritance tax.

- Until next time.