I Will Teach You To Be Rich 4 – Expertise and Asset Allocation

Today’s post is our fourth visit to a new book, the popular I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi.

Contents

Experts

Chapter 6 of Ramit’s book is about expertise and the lack of it.

He starts by demolishing the expertise of wine critics, who couldn’t tell the difference in a blind tasting between white wine and the same wine coloured red with food dye.

- They used completely different words to describe the two wines.

I think he’s on to something here, but it’s complicated.

- I think that most people overestimate their ability to appreciate higher-end wines, and are wasting their money if they buy them.

- At the other end of the scale, mass-market wine (particularly from the New World) has changed out of all recognition during my lifetime, and there is a lot of stuff that I now find completely undrinkable.

Ramit – like Michael Gove on the British public – has had enough of experts, and in particular of stock-pickers.

It’s true that financial talking heads in the media are in general dismal, but that’s as much down to the media (and to the public’s taste) as to the experts.

- The dull truth doesn’t sell tickets. (( As I can testify after writing this blog for more than six years ))

On to active funds, which as Ramit says, don’t beat passive funds.

- But they can’t (on average) by definition, so that doesn’t prove much.

Active funds have higher costs (the manager and the research) so they underperform the index by more.

- But some truly active exposure can lower the volatility of your portfolio and improve your Sharpe Ratio.

Closet trackers (active on the outside, passive on the inside, and high cost) are the funds that you really need to avoid.

Most people are lousy stock-pickers, but most people play lousy piano, too.

- And there are many investors who have outperformed for many years (Ramit mentions Buffett, Lynch and Swensen, but there are lots of others, with different styles).

Outperformance factors such as momentum, value, low vol and small size are well-known, though nothing works all of the time.

It’s hard to find the very best stocks and asset classes, but you can aim lower and still do well.

- Learn to avoid the worst stocks and funds, and those whose prices are already falling.

But Ramit is right to call out stock picking as the commonly perceived definition of being an investor.

- For most serious investors, stock picking is just a small part of the overall picture.

Financial advisors deserve a mention, too.

- Apart from being too expensive for most people (including me), they aren’t investing experts.

And although the commissions conflict has supposedly been fixed, other conflicts remain.

- Most advisors have a relationship with just one investment platform.

Here in the UK, IFAs are good at ticking regulatory boxes, and some can also help with psychological hand-holding.

But most of them outsource the investment process to yet another layer of “experts”.

- Which means that most people can easily learn to do without them.

Ramit also poo poohs market timing, which I believe in, to an extent.

- There are ways to protect yourself against a crash, but most people can safely ignore them.

I think Ramit conflates useless speculation and forecasting with serious analysis of optimum portfolio weightings.

Ramit’s alternative to experts is going full passive, which opens you up to a different set of challenges.

- An obvious one is that market cap indexing biases you to expensive stocks – an index is not necessarily the “fair ruler” that you think of.

But to be fair to Ramit, such problems aren’t ones that his target audience will quickly come up against.

- Passive indexing is a fine approach for your first £100K in investments.

Best days

Ramit quotes the old story that if you are out of the market during the best few days (twenty or forty, over fifteen years) then your overall returns plummet.

- Which is true, but the nature of stock markets means that the best days are closely associated with the worst days, which you would also likely miss.

This pattern also applies to annual returns and explains why I prefer studies which use historical returns rather than Monte Carlo simulation.

- Bad periods (particularly the worst periods) tend to be followed by good ones, and Monte Carlo fails to capture this.

Survivorship bias

Ramit points out that bad funds die or are killed off, which makes the performance of the group (based on the survivors) look better.

- Which is true, but new funds will spring up to replace the dead ones, so in high-level studies this won’t have too much impact.

Look out for this trick when a fund house highlights its best two or three funds, though.

Asset Allocation

Chapter 7 is about putting together a simple portfolio which Ramit says will make you rich.

Risk tolerance

Ramit starts with a simple 3-question questionnaire on attitudes to investing.

I think the most useful questionnaire you can answer is one about risk tolerance.

- Ours has twenty questions, and you can take it here.

Ramit’s aim is to sort people into long-term, medium-term and short-term thinkers.

- The first two groups are pointed towards tracker funds and lifecycle/multi-asset funds respectively.

The third group – most likely cautious non-investors – is told to mend it’s ways.

Automatic investing

Ramit’s investment solution is regularly investing in a static asset allocation of low-cost index funds – dollar-cost averaging (DCA) in other words.

Because equity markets trend up, DCA will actually lose you money on average (compared to lump-sum investing).

But most people in the accumulation phase only have the money that they save from each paycheck to invest, so monthly DCA is fine, so long as you can keep the transaction costs down.

- If not, save the money in cash until it hits your minimum deal size (£3K, £5K or £10K).

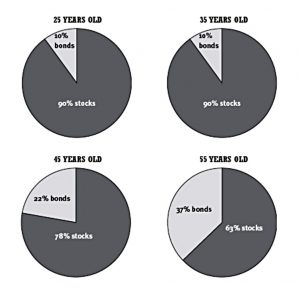

Asset allocation

Ramit reminds us that:

More than 90% of your portfolio’s volatility is a result of your asset allocation.

Bonds have much lower volatility than stocks, so minimising volatility means you would hold a lot of bonds (60%+).

- But bond returns are generally lower, so we need to compromise in order to hit our return targets.

For most people (targeting a 3% pa real return or withdrawal rate) the optimum allocation is 75% stocks, 20% bonds, 5% true alts (eg. gold, macro hedge funds).

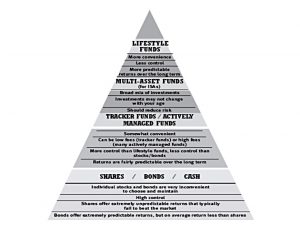

Ramit’s pyramid

Ramit has a “pyramid of investing options” which I don’t think adds much value.

I will assume here that readers understand what a stock and a bond are.

The main flavours of stocks are market cap (large, mid and small) and geography (country/region).

- The main favours of bonds are government, corporate, term length (length of time until you get your money back) and whether their returns are index-linked.

You can also buy stock funds which exploit the outperformance factors we mentioned earlier (momentum, value).

Ramit is basically saying that you can invest in individual stocks, or tracker funds.

- With bonds, you would be in funds from the start, since bonds trade in too large a size for retail investors.

There are two extra flavours of tracker funds – multi-asset (good) and lifestyle (bad).

Lifestyle funds are bad because they belong to an era when retirees bought an annuity at age 60 or 65.

- Nowadays annuities offer spectacularly bad value, and many retirees will need to manage their own portfolio for 30 or 35 years.

This makes the gradual shift from stocks to bonds – starting as soon as age 50 – in lifestyle funds inappropriate.

Here are the Vanguard lifecycle allocations:

Multi-asset funds are good for people with small pots (because they are properly diversified).

- But once you have more than £50K you can start to buy multiple funds and access the asset-classes you like.

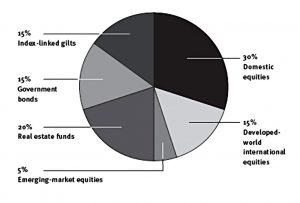

DIY Swensen

Ramit also highlights the Swensen allocation (a much-simplified version of the approach used in the Yale endowment fund):

This is good, but you can do better on your own with a big enough portfolio (say £100K+).

And that’s it for today.

- There was a bit more meat in today’s chapters, but I disagree with Ramit on some basic stuff (passive only, lifestyling, very few funds etc).

The next article in the series will be the last (apart from a summary) and will cover maintenance and life events.

- Until next time.