Limits to Growth

Today we’re going to look at the limits to growth.

Contents

Environmental impact

We live in a capitalist economy driven by continuous growth (in GDP in particular). But are there limits to how much we can grow the economy?

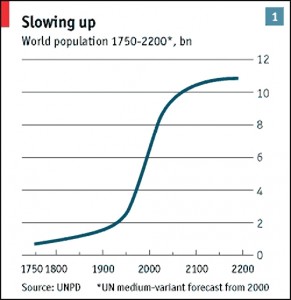

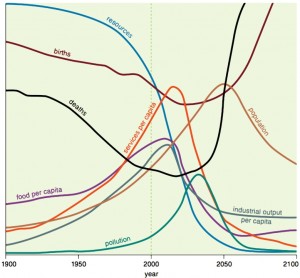

Doom-mongering about the future was popular back in the 1970s, when the sharp rise in the earth’s population came into focus. ((The graphic at the top of the article is a modern – and squished – version of a famous chart from a 1972 book called Limits to Growth; the un-squished chart appears later in the article))

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=193149858X&template=thumbnail]

Worries over the exponential growth of the population date back more than 200 years, to Thomas Malthus. Luckily, technological progress has been faster than population growth.

Fears about population growth have receded since the 1970s, as the rate of growth itself has slowed. The buzz nowadays is mostly around climate change and greenhouse gases.

Environmentalists in general have four main claims about the human impact on the planet:

- natural resources are running out

- the population is ever-growing and will run out of food

- species are becoming extinct – forests are disappearing and fish stock collapsing

- air and water are becoming more polluted

We’ll examine these claims more closely later.

But alongside this, people – often non-economists – have begun to question whether economic growth can continue forever for physical rather than economic or environmental reasons.

Exponential Growth

Tim Harford, writing on the Freakonomics blog, explains that exponential growth is the problem. He illustrates this with the rice on the chessboard story:

“The inventor of chess was offered a reward by a delighted king. He requested a modest-sounding payment: one grain of rice on the first square of the chessboard, two on the second, four on the third, doubling each time. Yet this is actually a colossal amount—many times the annual rice production of the entire planet.”

The chessboard story uses 100% “annual” compounding, but even with the more normal 2% or 3% pa, you end up in the same place eventually.

Tom Murphy

Tom Murphy is a physics professor at University of California San Diego. He writes a blog called Do the Math, which “uses physics and estimation to assess energy, growth and options.” He is mostly critical of alternative energy sources (apart from solar) and thinks that economic growth will stall in the future.

His most famous post is “Exponential Economist Meets Finite Physicist.” Here he imagines / remembers a dialogue between a physicist and an economist over the course(s) of a dinner about the limits to growth. Tom’s position is that many basic economic concepts are inconsistent with the laws of physics.

Murphy’s dialogue

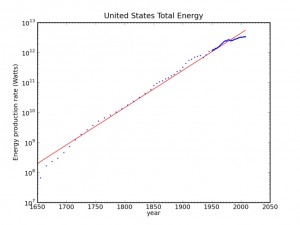

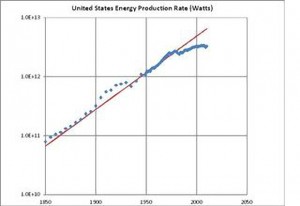

Murphy starts by looking at historical energy consumption. Since 1650, energy growth has grown by 3% a year.

Some of this has been driven by population growth, but per capita energy consumption has also increased dramatically over the period.

Admittedly, the growth rate has slowed recently (more on this later).

Murphy decides to use a 2.3% growth rate going forwards, since this means that energy use would increase by 10 times each century.

Murphy’s basic argument is that exponential growth (in energy use at least) can’t continue forever, because:

- at 2.3% growth pa, waste heat will boil the Earth in 400 years (and we would be using the entire solar input of energy that strikes the earth)

- after 2,500 years we would be using the entire energy output of the Milky Way (our home galaxy)

Energy efficiency might offer a way forward, but some things (electric motors) are already at 90% efficiency, and even power plans are 30% efficient, so there are not many more “doublings” of efficiency possible. Food is another area where increased energy efficiency is difficult.

Murphy argues that a limited, scarce resource like energy, that is fundamental to every economic activity cannot become arbitrarily cheap, and so must limit GDP in the end. Energy comprises around 10% of GDP today, and for GDP to rise while energy does not (over some long-term time scale), energy must make up a smaller proportion of GDP, by becoming cheaper.

Critiques of Murphy

- 400 years is a long time, and 2,500 years is even longer; people don’t make economic and financial plans over these timescales

- the “long-term trend growth” used in growth and business cycle models is a trend that lasts longer than the business cycle, so a decade or two

- eventually the sun will explode and destroy the earth and the human race in any case

- Murphy’s economist comes up with a virtual reality / Matrix scenario that would be lower energy

- virtual apples, piped directly to the brain’s pleasure centers, would be as satisfying as real apples, but much cheaper to create in terms of energy

- significant improvements in the energy efficiency of the computing power needed to run the VR system would be needed

- this coma-like state doesn’t represent continuation of economic growth as we presently understand it

- Murphy’s assertion that energy can’t become arbitrarily cheap may be wrong.

- Murphy’s argument is that if energy became arbitrarily cheap, someone could buy all of it, and all the activities that comprise the economy would grind to a halt (eg. food would stop being produced)

- This in turn means that people would be willing to pay more for energy, so there would be a floor for energy prices as a fraction of GDP

- The only way for energy to become very low-cost is for it to become either very abundant or to be only needed sparingly

- In practice, when someone tries to corner a market the price of the commodity in question would rise to reflect its increasing scarcity until the buyer runs out of money

- It’s not clear to me how the price of energy would either rule out or rule in an end to growth

- Energy growth is not the same as economic growth.

- GDP measures what people are willing to pay for, which is not necessarily connected to the use of energy, or any other physical resource.

- Energy growth per person in developed economies has been negative over the last 25 years

- This is partly due to offshoring to less-developed economies, but also to do with changes in what is being bought and sold.

- Tim Harford makes the point that New York – with all its high-end economic activities – uses less energy per person than the rest of the USA; perhaps this is what the future looks like.

- Noah Smith thinks that the problem of “local non-satiation” – no matter how much you have, you always want more of something – will be solved via “desire modification technology”

- by changing our desires directly, we would like the world we have, more and more

- eventually we would like the world so much that we don’t want anything to change, which means we no longer need to grow the economy

- this seems to assume a magical levelling of the playing field between rich and poor, young and old, and across the wildly different cultures of the earth

- if not, the “technology” must be something closer to the soma of Brave New World – or to the Matrix – than I had imagined

Environmental claims

The environmental claims we noted earlier don’t stack up:

- energy and other natural resources have become more abundant since “The Limits to Growth” was published in 1972

- extractable oil reserves now stand at 150 years supply

- solar energy falls in cost by 50% each decade

- reserves of aluminium, iron, copper, gold, nitrogen, zinc and cement have also increased

- this abundance is reflected in decreasing real commodity prices (down 80% since 1845)

- population growth is now slowing, but we have never come close to running out of food

- food is more abundant and cheaper than ever before (down 90% in real terms since 1800)

- more food per head is now produced than at any time in history, and fewer people are starving

- only 0.7% of species are expected to disappear in the next 50 years, not the 25-50% that was predicted

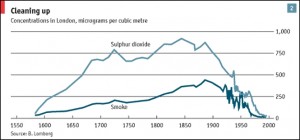

- environmental pollution appears to be transient – associated with the early phases of industrialisation

- air pollution diminishes when a society become rich enough to care about the environment

- London air is now cleaner than at any time since 1585

- this means that the best cure for pollution is the acceleration of economic growth

- greenhouse gases may be an exception to this rule, depending on the human response to the problem

- economic analyses show that it will be more expensive to cut CO2 emissions radically than to pay the costs of adaptation to the increased temperatures they will cause

- the money earmarked for reducing emissions would be better spent on things like providing universal access to clean drinking water and sanitation

Conclusions

- There is a limit to everything, even growth.

- The real question is whether the limits will impact behaviour in our lifetimes.

- Economic growth need not slow because of environmental considerations.

- Climate change will happen, and should be adapted to, rather than “prevented”.

- Constant energy growth would cause serious problems to the planet within 400 years (more likely, in 200 years).

- Solutions which involve reduced energy usage via a virtual reality / Matrix approach are not continued growth as we know it.

- The end of economic growth because of desire modification technology is a long way from what most people mean today by the end of growth.

- Economic growth (or GDP growth) is not the same thing as growth in energy, or growth in population – GDP (economic activity) can increase without either energy use or population increasing.

- GDP, the most common measure of growth, has many flaws; meaningful development in society – increases in the “quality of life” or in “happiness” – could be possible without growth in GDP (or in energy usage), though again this is not continued economic growth as most people understand it today.

I don’t think we have too much to worry about in the short-term.

Apart from of course:

- the impending robotics and software automation revolution

- the internet of things

- the impact of developing countries attempting to attain a western middle-class lifestyle, and the consumption that goes with it

- climate change

And in the long run, we are all dead.

Until next time.

Sources

- Exponential Economist Meets Finite Physicist – Do The Math

- Murphy’s Law? or, Follies of a Finite Physicist – Noah Smith

- Can Economic Growth Continue Forever? Of Course! – Tim Harford, Freakonomics

- The truth about the environment – Bjorn Lomborg, The Economist

- What Tom Murphy doesn’t show you – Mark Mahner, Random Thoughts