GDP – time for a change?

Today we’re going to look at GDP, and whether it is, or ever has been, a useful number.

Contents

Preamble

Regular readers will know of my interest in what will happen to the economy as workers are displaced by robots and software algorithms.

One of the possible consequences is that the welfare state may have to be replaced by some kind of basic income, as the number of people not skilled enough to compete with automation increases.

Taking this a step further, the whole notion of a consumer economy driven by constant growth may be in question.

This is a subject I will return to in a later post, but first I want to look at the most commonly used measure of growth – gross domestic product, or GDP.

The books

GDP seems to be in the zeitgeist, with four recent books on the subject.

First up is Diane Coyle’s book GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0691169853&template=thumbnail]

The second book is The Little Big Number: How GDP Came to Rule the World and What to Do About It by Dirk Philipsen, an American economic historian and environmental advocate.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0691166528&template=thumbnail]

Book number three is by Zachary Karabell and is called The Leading Indicators: A Short History of the Numbers That Rule Our World.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=1451651228&template=thumbnail]

Finally there is Mis-measuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up by Joseph Stieglitz

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=1595585192&template=thumbnail]

The history

Every quarter the financial markets wait for GDP numbers. GDP up means growth, GDP down (for two successive quarters) means a recession. But a hundred years ago nobody measured the size of the economy.

Industrialisation led to explosive growth in productivity and wealth between 1850-1929. There were regular boom and bust cycles, but at the time nobody knew why this was happening.

The hope was that market forces would take care of things. It took the Great Depression and World War Two to persuade politicians than some numbers were needed.

In 1929 the US stock market crashed and by 1932, the US economy was in deep trouble. Companies and banks were going bankrupt and a third of the workforce was unemployed.

The Commerce Department hired economists to figure out why. Through questionnaires, they generated the first ever comprehensive data set of national income. This covered what was being produced, investments and profits, and underlying resources.

GDP emerges

A Russian American economist called Simon Kuznets – who later won the Nobel Prize for this work – came up with the measure we now call GDP (originally GNP), which focuses on monetary transactions. He was supported from this side of the Atlantic by John Maynard Keynes.

GDP measures the goods and services produced by a single country. ((GDP includes all production within a country regardless of the national origins of the individuals or companies generating it. GNP includes the production of any citizen or domestic company regardless of where it is located.))

Kuznets and others made several significant decisions. The most crucial was to leave out domestic work, apparently because it was hard to assign a market value to it. ((Now that so many domestic services can be bought-in, market comparators are readily available and this seems a major oversight; even in the 1930s, using some form of minimum wage as a base would have been preferable to exclusion))

The orthodoxy

This became the foundation for measuring the effect of the innovative and controversial New Deal policies introduced to address the Depression. Conveniently, GDP analysis supported the thinking of Keynes and others that governments should spend more in recessions to stimulate demand.

Then came the second world war, which really ended the Depression. The Allies used GDP to track the effect of the war on their economies.

US and UK officials wanted to know how much domestic production could be diverted to the war effort without their countries running out of basic goods. GNP allowed them to calculate how spending and matching tax-raising could happen without triggering inflation or permanently damaging the domestic economy.

After the war, there were countries to rebuild. People feared another depression, since they didn’t understand where the first one came from. Increasing productivity was seen as the solution for increased profits, a large tax base for government, and increased employment and wages for workers.

The US encouraged the spread of GDP through Bretton Woods, the United Nations, and the Marshall Plan. GDP became established as the standard for measuring an economy, and also for welfare and progress. Globalisation entrenched its position as the metric for comparison in international trade and finance.

The academic critique

Many would say the focus on money has distorted our view of the economy, and also society. In 1968, Bobby Kennedy famously pointed out that GDP “does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play” – “it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

We’ll come back to the quality of life issues in a moment, but first the eight main academic criticisms:

- free (or DIY) doesn’t count:

- if I wash my own car or my windows, GDP doesn’t capture this, but if I pay someone it does ((Most work in the home, including cooking, cleaning and child-rearing, plus hobbies and growing your own food is therefore invisible))

- restoration of the status quo seems like an improvement:

- if I crash my car and have it repaired, GDP goes up, but the car is in the same state it was, and resources have been used up to fix it

- the same goes for hospital bills spent on sick people – are we really better off after paying for that CAT scan? ((Alan Greenspan, an early champion of GDP observed in the 1990s – when he was chair of the US Federal Reserve – that buying air conditioners would boost GDP, as would the spend on electricity to run them; thus cooler Vermont might show a lower GDP than hotter Alabama, for no good reason related to prosperity or quality of life))

- bad things seem good:

- guns and other armaments and cigarettes all boost GDP

- public health and environmental impacts are ignored

- GDP has no “direction” – it is scalar rather than vector

- the “black economy” is ignored:

- illegal drug transactions, work done by unregistered immigrants and prostitution are obvious examples

- quality / efficiency / productivity improvements are ignored:

- from things as universal as the internet and the services than run on it, ((Wikipedia, Facebook, Google and this blog are all free))

- to faster, more powerful computers & smartphones,

- to LED lights and the HD TV in my living room, to the food on my dinner plate

- the vast improvements to my quality of life over the past 30 or 40 years have been ignored

- getting more out of something without paying, or spending less to get the same effect has a negative effect on GDP

- GDP increases with government spending:

- GDP = (C + I + G + [X - M]) – consumption plus investment plus

government spending plus net exports - this gives governments an incentive to spend

- and government spending is calculated from government workers’ salaries, not the value of their output

- austerity is therefore a brave path to follow

- GDP = (C + I + G + [X - M]) – consumption plus investment plus

- it’s difficult to calculate reliably and open to manipulation:

- GDP numbers are frequently subject to revision, sometimes by substantial amounts

- Italy increased GDP overnight by 20% in 1987 by including the informal economy

- more recently, sub-Saharan African countries such as Ghana reported 60% GDP increases when price index weightings changed

- topically, Greece famously manipulated its GDP to enter the Euro currency union

- the contribution of the financial sector to GDP is problematic:

- Coyle points out that in the UK’s GDP figures for 4Q2008, the financial sector showed record growth

- this was when the sector required massive government bailouts, so something must be wrong

- the issue is that many banking services are not explicitly charged to customers (eg. deposit taking and lending are funded by the spread in interest rates for these services)

- the “solution” is FISIM ((Financial Services Intermediation Indirectly Measured – the international

standard for measuring bank contributions to GDP)) – the difference between the interest rates on and deposits and a benchmark risk-free rate, multiplied by the outstanding loan balance - FISIM takes no account of risk, so the increased risk taking and leverage by banks before the 2008 crisis appeared as ‘growth’ in GDP

- studies have found that adjusting for risk taking could reduce financial sector contribution to GDP by 25-40%

The green critique

Recently the environmental lobby (which includes Philipsen) have focused the debate on the damage done to natural resources by a society driven by mindless consumerism.

Digging up (and burning) oil and coal adds to GDP, but the depletion of resources and the damage from additional CO2 in the atmosphere is not accounted for. Philipsen draws a parallel with Easter Island, where the civilisation collapsed after the inhabitants used up all the tress.

Philipsen also sees GDP growth as the objective of government planning – “this purely descriptive tool of output transformed into something prescriptive; productivity increase became the goal and the very definition of a national economy.”

But in the UK at least, targets for unemployment levels and inflation rates have been and continue to be more important. Consumption may be the driver of the economy, but production is the destination for now.

By-products

Whilst GDP ignores the downside of economic growth, it also ignores the benefits:

- life expectancy has increased in rich countries

- infant mortality has decreased

- life is infinitely more comfortable now than 50 years ago

Rebuttal

There is some truth in the environmental argument, at least in terms of omission, but the implication that growth means destruction is false.

Staying close to home, Britain is much richer (and has a much larger GDP) than when I was a child, but it is also much safer and cleaner. Improved technology also needs to be taken into account.

Per capita oil consumption peaked in the 1970s because the higher prices since then ((Until recently, at least)) suppressed demand.

The green critique also needs to be compared to the alternatives. A carbon tax on fossil fuels would hit the poor hardest, since energy makes up a greater proportion of their budgets. It would increase unemployment as jobs were lost in those industries, and – in the short-term at least – here in the UK we would find it difficult to generate sufficient electricity.

Green campaigners tend to focus on the critique and not the solution.

The Bhutan experiment

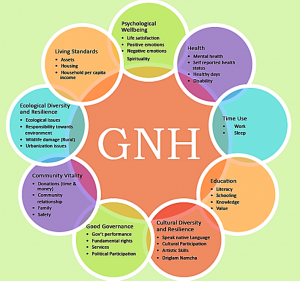

In 1972 the King of Bhutan coined the phrase “Gross National Happiness” (GNH) as a commitment to building an economy on Buddhist spiritual values and Bhutan’s culture instead of the western material development represented by GDP.

The four pillars of GNH philosophy are:

- sustainable development

- preservation and promotion of cultural values

- conservation of the natural environment

- establishment of good governance

Over the years the model developed into a framework involving 32 measures across nine areas:

The current prime minister has distanced himself from GNH, as it has proved difficult to deliver. Bhutan is a poor country with most of the population engaged in subsistence farming. Many of the GNH values are unattainable for the masses.

Instead the country now focuses on concrete goals such as “a motorized roto-tiller for every village and a utility vehicle for each district.” External debt is more than 90% of GDP.

Bhutan appears to show that – flawed as it is – a focus on GDP may produce more happiness than a focus on GNH. Studies of immigration also support this – the direction of flow is almost always to the country with the higher GDP.

Conclusions

- GDP does not measure welfare or inequality, nor happiness and contentment

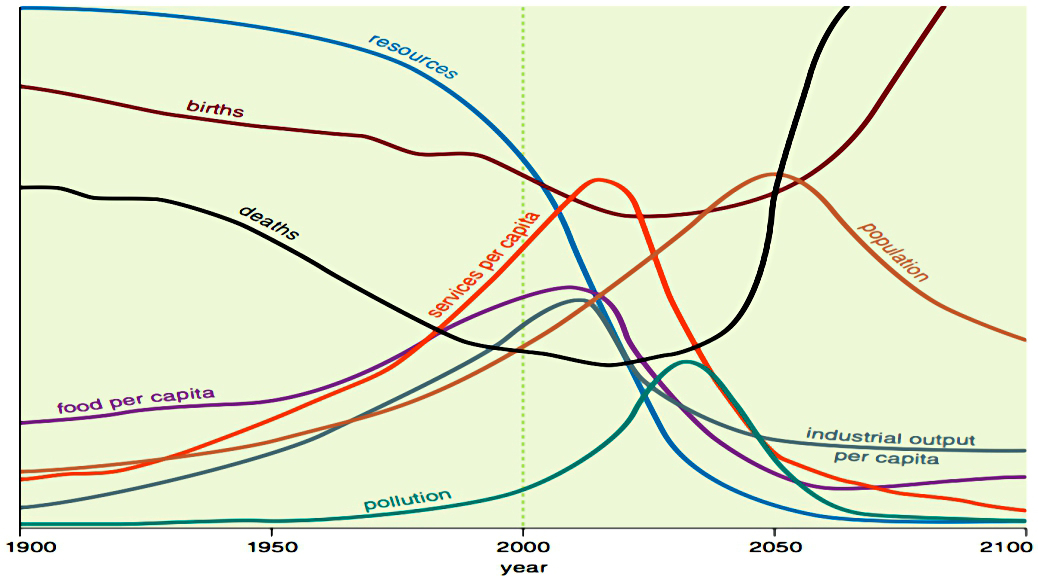

- Unending growth is unsustainable in the medium- to long-term ((We’ll look at why this is in a future post))

- A consumption-driven economy is wasteful and inefficient, but it can lead to rapid innovation and progress

- We probably need a measure of well-being, and it probably needs to become more prominent than GDP in certain aspects of decision-making; agreeing how this measure should be calculated will be politically difficult at a regional, national and global scale

- More likely in this age of “big data” is a national “dashboard” of five or fifty indicators representing the complexity of the age and the fragmentation of society; global corporations will need (and possibly already have) their own dashboards; perhaps individuals will need them too

- Sustainability and inequality are already on the political agenda – for example, NIMBYism is a real issue in the UK

- GDP will remain useful for certain purposes, for at least a generation after any well-being measure / dashboard is introduced

- Radical and/or rapid changes to the existing GDP number risk our already limited ability to direct and control the economy

Until next time.

Sources

-

Wrong number? – The Economist

-

Dirk Philipsen talks new book – Duke University Keenan ethics institute website

-

(Mis)leading Indicators: Why Our Economic Numbers Distort Reality – Z

-

Two book reviews – Tyler Cowen, Washington Post

- Book Review – Nicholas Dunbar

I would like to get a copy of your newsletter

Regards

Hi there,

There’s a sign-up form at the very top of the page, and another at the bottom of the left-hand sidebar.

Mike