Mark Ritchie – God in the Pits

Today’s post is a profile of Guru investor Mark Richie, who appears in Jack Schwager’s book New Market Wizards. Her chapter is called the Music of the Markets.

Contents

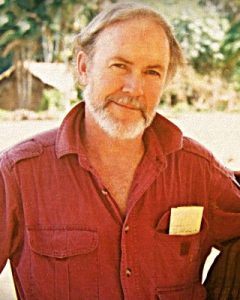

Mark Ritchie

Mark Ritchie is one of the founders (along with his brother Joe) of CRT (Chicago Research and Trading), a kind of arbitrage hedge fund.

CRT doesn’t go for home runs. It is in the business of extracting the many modest profit opportunities that are continually created by the small inefficiencies in the marketplace.

CRT is constantly tracking approximately seventy-five different markets, traded on nineteen worldwide exchanges, with sophisticated trading models instantaneously signaling which financial instruments are relatively underpriced and which are overpriced.

Ritchie appears in Jack Schwager’s book New Market Wizards.

- His chapter is called God in the Pits, a reference to Ritchie’s autobiographical book which Schwager describes as:

A highly unusual blend of spiritual revelations, exotic experiences, and trading stories. The title refers to Ritchie’s convictions about the presence of God that he perceives in his life.

Early days

Ritchie grew up poor and went to divinity school.

- He became hooked on trading when his brother Joe visited the Chicago Board of Trade.

About six months after our visit to the exchange, Joe’s company sponsored him to start a silver arbitrage floor operation. Several months later, I got a job with the company as a phone clerk on the floor.

Richie spent most of his trading career on the CBOT floor, trading soybeans.

- When Schwager interviewed him, he had been off the floor for five years.

Performance

Ritchie started (off the floor) in 1987 with $1M.

- He averaged 50% pa for the next four years.

Position size

I have a rule that whenever I’m still thinking about my position when I lay my head on my pillow at night, I begin liquidation the next morning. If I find myself praying about a position at any time, I liquidate it immediately.

Magnitude of losses and profits is purely a matter of position size. Controlling position size is indispensable to success. Of all the traits necessary to trade successfully, this factor is the most undervalued.

The successful trader must be able to recognize and control his greed. If you get a buzz from profits and depressed by losses, you belong in Las Vegas, not the markets.

Ritchie’s initial position size is just half a per cent of his portfolio.

Panic

You have to be able to think clearly and act decisively in a panic market. The markets that go wild are the ones with the best opportunity.

Usually the way we miss opportunities in this business is by saying, “It looks too good to be true,” and then not doing anything. Too often we think that everybody else must know something that we don’t, and I think that’s a critical mistake.

Any investment opportunity that everyone else is doing is by definition a bad idea. The reason markets get out of line is because everyone is doing the wrong thing.

[You need] the ability to implement your ideas despite adverse conditions. There is no opportunity in the market that is not an adverse condition situation.

You can prepare for it by having a game plan. You have to know what you’re going to do when the market gets out of line.

Risk control

Most people don’t distinguish between drawdowns in open equity [unrealised profits] and drawdowns in closed equity [a losing trade]. If I protected open equity with the same care I protected closed equity, I would never be able to participate for a long-term move.

Any sensible overall risk control measure could not withstand the normal volatility in such a move. If you get too careful about not risking your gains, you’re not going to be able to extract a large profit.

Stay away

My advice to people has always been: Stay out of the business; stay completely away from the market.

For novices to come in and try to generate profit in this incredibly complex industry is like me trying to do brain surgery on the weekends to pick up a little extra cash.

I think they can go with some of the managed funds or trading advisors that have proven track records. But “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

Also, I don’t think you can make money unless you’re willing to lose it. Unless you have money that you can afford to lose and still sleep at night, you don’t belong in the market.

My willingness to lose is fundamental to my ability to make money in the markets.

Charity

Ritchie invests a third of his profits in charitable works, in particular with an Amazon tribe.

I don’t think in terms of charity. I think in terms of investing in the poor. What the poor need are cottage industries that allow them to become self-sufficient.

If I could set up a system where I could make money off the poor, then I would have achieved my goal.

Charity tends to spawn dependency. In contrast, if I can establish someone in a business where he can return my money, then I know his situation is stable.

Trading style

Ritchie is a relatively long-term trader.

- He switches position (from long to short, or vice versa) between one and five times per year per market.

Of course, I would prefer only one trade per year. My best trade ever was one that I held for over four years.

Conclusions

This chapter in Schwager’s book is very entertaining, but a lot of it is taken up with pit trading anecdotes that don’t carry across to the private investor.

Schwager identifies five principles that Ritchie uses:

- Do your own research.

- Keep each position size small.

- Stay with a winning position.

- View open profits differently from the starting equity in a trade.

- Recognize and control your greed.

They sound pretty good to me, though number four has some challenges in implementation.

- It’s hard to be tough with one hand and generous with the other.

Until next time.