Peter Gyllenhammar – Corporate Engineer

Today’s post is a profile of Guru investor Peter Gyllenhammar, who appears in Guy Thomas’s book Free Capital. His chapter is called The Corporate Engineer.

Contents

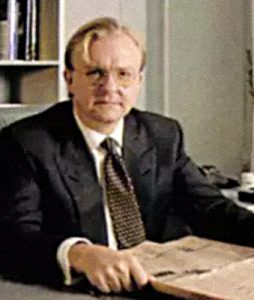

Peter Gyllenhammar

Peter Gyllenhammar is one of the (mostly) anonymous investors in Guy Thomas’ book Free Capital.

- The scale of his investment activities and his distinctive Swedish background meant that Peter waived the usual anonymity.

Peter was born in 1953 into a famous family in Sweden.

- A distant relative was head of Skandia, Volvo and Aviva.

His own father was first an army officer then later a property manager for a Swedish retailer.

Peter’s interest in investing started at age 14 with an inheritance from his grandmother that included a few shares.

- Later he discussed investment with his school woodwork teacher.

Peter is still based in Stockholm, with a staff of two investment executives.

- One looks after property, the other deals with Peter’s UK companies.

He spends the summer on his yacht in the Baltic, keeping in touch with the markets through satellite broadband.

Career

Peter was 56 at the time he was interviewed by Guy, having left his last full-time job at the age of 43.

He dropped out of Stockholm business school to found an investment management business (Trend Invest) aged 20 and later worked as an analyst and in corporate finance.

- He developed a reputation for identifying undervalued companies.

He also went bust twice before the age of 40.

UK micro-caps

In 1996, Peter started investing in UK micro-caps.

- He likes them because they are too small for most institutions, and there is a lower level of family control than in his native Sweden.

In less than 10 years, Peter turned £50K in UK small caps into tens of millions.

Trading Style

I have never felt that investing is like working. It more like playing ten parallel games of poker or chess.

I don’t try to construct a portfolio of shares around an index benchmark. I am always looking at the underlying businesses, and thinking what can be done to create value in them.

Peter buys companies trading below net asset value, and takes “negative control” – this means he owns 25% and can block special resolutions that need 75% to pass.

- Then he re-engineers the firm to release value.

I find troubled companies intellectually more interesting. I enjoy restructuring and creating value.

Guy writes:

By holding a larger fraction of a company, you can influence events more decisively. You can change corporate strategy, change the management, or negotiate mergers or asset disposals yourself, thus directly creating value rather than passively awaiting events.

Often these are companies with institutional investors whose stakes Peter can buy.

- Sometimes the companies will be delisted, but he might retain control/ownership.

I am good at looking at lots of companies and working out the concept of what needs to do be done. I am not so good at implementation, and I am certainly not a good manager of people.

Leverage

Early on, Peter used a lot of leverage – hence why he went bust twice.

- Now that he is rich, he doesn’t used leverage and his portfolio has become more diversified.

He still has debt on his Swedish property portfolio, but it is secured only against the properties themselves.

Case studies

The chapter includes a couple of case studies of companies that Peter invested in – sometimes more than twenty years ago as I write.

- I couldn’t find much in these that would be actionable by today’s private investors in the UK.

A common theme seemed to be releasing negative working capital which could then be re-invested in other special situations.

Advisors

Peter only uses advisors when regulation forces him to do so.

As well as advisors for takeover bids, we are obliged to use advisors when we implement investment strategies for pension funds, publish audited accounts, and so on.

But often the advice is box-ticking and rubber-stamping of what we have already decided to do, rather than a real input to our decision. And in some situations the best course is judicious disregard for the advice.

Mistakes

Peter attributes his mistakes to three main reasons:

- Poor research.

- Poor management or supervision.

- Too much debt, including pension fund deficits.

I have learnt that it is not sensible to have a large stake and leave yourself entirely in the hands of management.

Corporate governance

Peter often meets opposition when trying to get a seat on a company board.

- The UK system means that directors are appointed by a committee of existing directors – what Peter calls a “back-scratching gang of insiders”.

The UK rules are good at creating work for the advisors. They are less good at empowering shareholders to influence corporate decisions.

Conclusions

There’s not much here for the private investor, and indeed I wonder whether Peter should have been included in Guy’s book.

- He’s undoubtedly a shrewd analyst, and he’s prepared to put his (and other people’s) money where his mouth is.

But his strategy is too high-risk and high-stakes for most people.

- He’s more of a corporate raider/asset stripper than the typical “ISA millionaire” in Guy’s book.

Until next time.