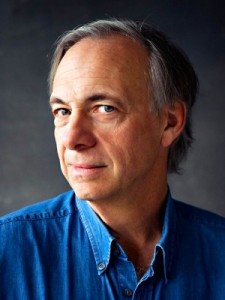

Ray Dalio – The Man Who Loves Mistakes – Investor Profile

This article is part of our ‘Guru’ series – investor profiles of those who have succeeded in the markets, with takeaways for the private investor in the UK.

You can find the rest of the series here.

Contents

Ray Dalio

Ray Dalio is the founder of Bridgewater, for some time the world’s largest hedge fund ($120 bn in assets, 1,400 employees). According to Forbes, in 2014 he was the 30th richest person in America and the 69th richest person in the world with a net worth of $15.2 bn.

Dalio named his flagship fund Pure Alpha and has been critical of hedge funds that derive most of their return from beta, but still charge high fees.

Much of what is packaged as alpha is really beta sold at alpha prices.

Dalio appears in Jack Swchager’s book Hedge Fund Market Wizards. His chapter is called The Man Who Loves Mistakes.

Bridgewater

Bridgewater has made an estimated $50 bn for its institutional investors over 20 years (probably a record) at 22.3% pa gross (14.8% pa net), which is amazing for such a large fund. The fund is so large that it has been closed for several years, and now returns profits.

- Bridgewater has had only two drawdowns worse than 12% over 20 years, the worst being 20%.

- The fund has very low correlations to traditional equity and bonds and also to other hedge funds. Most hedge funds are 70% correlated to equities.

This may be due to the unusual “systematic fundamental” approach it employs.

- Bridgewater trades using a fundamentally based computer model that combines Dalio’s trading rules with an analysis of developed and emerging markets going back hundreds of years.

Corporate philosophy – mistakes and transparency

Dalio believes mistakes provide learning experiences that are the catalyst for improvement.

There is an incredible beauty to mistakes because embedded in each mistake is a puzzle and a gem that I could get if I solved it.

Each mistake was probably a reflection of something that I was (or others were) doing wrong, so … I could learn how to be more effective.

Most learning comes via making mistakes and reflecting on them.

Bridgewater has a 111-page Principles document containing Dalio’s philosophy and management concepts, many of which focus on mistakes:

- Mistakes are good if they result in learning.

- It is okay to fail but unacceptable not to identify, analyze, and learn from mistakes.

- You will certainly make mistakes and have weaknesses; so will those around you and those who work for you. What matters is how you deal with them.

The other core concept is transparency – meetings are taped and published to employees.

Trading history and lessons

Dalio started trading when he was 12, using tips from golf caddying – “I loved the game.” He was a kid in the 1960s when he remembers everyone talked about stocks – even his barber.

Schwager notes that many successful traders started at a young age. Dalio is not surprised.

Market thinking is different to school thinking, which is all about following instructions. It teaches you that mistakes are bad instead of teaching you the importance of learning from mistakes.

In the markets you can never be absolutely confident. You will always be looking at where you might be wrong. Dalio puts his ideas “out in front of other people for them to shoot down”.

- You have to be assertive and open-minded – an independent thinker.

Dalio’s first trade was a random winner.

- When he was 18, there was a bear market, and he started to go short.

- Then in college he started to trade commodities, attracted by the leverage.

In 1971, Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard. The stock market went up, which surprised Dalio.

- Printing money and currency depreciation was good for stocks.

- He also learned not to trust policy makers.

Trading is like working with electricity; you can get an electric shock.

In 1982, Latin America defaulted on its debt. The market rallied, because the Fed eased massively.

- Dalio learned not to fight the Fed.

- Easing can can swamp the impact of the crisis that causes it.

In the early 70s, Dalio was long pork bellies when they were limit down every day.

- It taught him the importance of risk controls.

In trading you have to be defensive and aggressive at the same time. If you are not aggressive, you are not going to make money, and if you are not defensive, you are not going to keep money.

Developing a system

Bridgewater’s system evolved from Dalio’s trader’s diary.

- He would write down the reasons behind every trade.

- Then he would compare what actually happened to his reasoning and expectations.

But his own direct experience was not enough – it would take too much time to get a representative sample.

- So he started to back-test his rules as well.

The rules in the system are monitored and revised when necessary (for example, the rules about the oil price were revised when North Sea oil was discovered).

Diversification – the Holy Grail

Dalio demonstrates to Schwager with a diagram (he calls it “the Holy Grail of Investing”) that stock-only diversification has limited impact (risk goes down by c. 15%), because of the 0.60 correlations between typical stocks.

- But if you combine assets with zero correlation, 15 assets will cut the volatility by 80%.

I can’t tell you which way the Greek/Irish bond spread would move in response to the S&P being down.

Dalio aims for “approximately 100 different return streams that are roughly uncorrelated”

Correlation

Dalio’s bigger point is that correlations change as conditions change.

- When economic growth expectations are volatile, stocks and bonds will be negatively correlated because if growth slows, it will cause both stock prices and interest rates to decline.

- When inflation expectations are volatile, stocks and bonds will be positively correlated because interest rates will go up with higher inflation, which is detrimental to both bonds and stocks.

Both relationships are totally logical.

- Gold and bonds are usually inversely related because inflation (current or expected) is bullish for gold and negative for bonds (because of higher interest rates).

- In early deleveraging, however, gold and bonds can move higher together, as easing reduces interest rates (ie. increases bond prices) and increases longer-term currency depreciation risk, which drives a flight to gold.

Correlation is just the word people use to take an average of how two prices have behaved together.

Using fundamentals rather than correlations allows Dalio to be forward-looking rather than backward-looking.

The biggest mistake

The biggest mistake investors make is to believe that what happened in the recent past is likely to persist. They assume that something that was a good investment in the recent past is still a good investment.

In reality, high past returns mean that an asset is more expensive, and a worse investment for the future.

It is human nature for people to choose strategies that worked well during the recent past.

Strategies that are based on a manager’s recent experience will work until they inevitably don’t work.

Quadrant thinking

The idea that the same fundamentals would have different implications under different circumstances is an essential component of Dalio’s thinking.

This often involves quadrants, like the BCG’s 2×2 matrices. Here two key factors and two states provide four possible conditions.

Bridgewater’s beta fund, the All Weather Fund, combines growth and inflation with increasing / decreasing:

- Growth increasing

- Growth decreasing

- Inflation increasing

- Inflation decreasing

Dalio thinks that changes in expected growth and expected inflation are the dominant reasons for some doing well when others do badly.

- Most portfolios overweight the assets suitable for “growth-increasing”, and suffer under other conditions.

Another matrix covers countries – creditors and debtors vs independent / dependent (monetary policy):

- Independent debtors (US, UK)

- Dependent debtors (Greece, Portugal)

- Independent creditors (Brazil)

- Dependent creditors (China, pegged to the dollar)

The system

- Trading is “99% systematised”, and entirely fundamental (no technical inputs).

- An event like 9/11 might produce a manual override, simply to reduce risk and exposure.

- Twenty or so significant uncorrelated positions will account for about 80% of the risk.

- Dalio doesn’t use stops, but does use position size limits.

- “We will limit our position size to assure that we can get out reasonably quickly and to keep our transaction costs small relative to the expected alpha of the trades in that market.”

- Position turnover is on average 100% every 12 to 18 months.

- Dalio avoids drawdowns by:

- balancing risk across multiple independent drivers

- stress-testing his strategies through multiple time frames and multiple scenarios (and countries)

- Dalio doesn’t believe in reducing exposures when he has a losing position.

- But he does use losing positions as a prompt to re-examine his strategy.

Deleveraging – The Big Picture

Dalio looks at three underlying forces in order to determine where we are economically:

- Productivity growth – real per capita GDP

- Long-term credit expansion / deleveraging cycle

- The business cycle

- fluctuations in economic activity caused by central bank changes to the availability and cost of credit

Of these, the most relevant today is deleveraging.

Deleveragings are very different from recessions.

The 2008 crisis triggered the first deleveraging in the US since the second world war. Dalio anticipated this using a “depression gauge”:

- interest rates below a certain low level

- contractions in private credit growth

- declining stock market

- widening credit spreads

If the depression gauge is triggered, Bridgewater’s system rules and risk constraints are adjusted, according to lessons from the study of what happened in the 1930s in the US, and in post-1990 Japan.

Here’s how the long-term credit expansion / deleveraging cycle works.

First, the availability of credit expands spending beyond income, and is self-reinforcing

- rising spending generates rising net worths (from assets like houses), which raise borrowers’ capacity to borrow

- The up-wave in the cycle typically goes on for decades, across several business cycles

- Ultimately credit can’t be expanded further

Eventually the debt service payments become equal to or larger than the amount we can borrow and the spending must decline.

This is deleveraging.

- The person spending $110K pa and earning $100K pa now has to cut his spending to $90K pa for the same number of years.

- Assets need to be sold, making asset values fall, which reduces the value of collateral, and therefore incomes and credit. Self-reinforcing again.

In recessions, interest rates can be cut enough to:

- ease debt service burdens

- stimulate economic activity because monthly debt service payments are high relative to incomes, and

- produce a positive wealth effect

In deleveragings (deflationary depressions):

- interest rates hit 0% and can’t be lowered further

- other, less-effective ways of increasing money are used

- borrowers remain over-indebted, making sensible lending impossible

- money goes in inflation hedge assets (stocks and property) because investors fear that their lending will be paid back with depreciated money

The really big picture

Dalio also believes in a five-phase cycle for countries:

- Countries are poor and think that they are poor.

- Countries are getting rich quickly, but still think they are poor.

- Countries are rich and think of themselves as rich.

- Countries become poorer and still think of themselves as rich.

- Countries go through deleveraging and relative decline, which they are slow to accept.

Stage 4 is the leveraging up phase.

- It ends with bubbles and / or wars, and the accumulation of debt that can’t be paid back in non-depreciated money.

In Stage 5, the central bank prints money and cuts real interest rates.

- This increases nominal GDP growth above nominal interest rates and so eases debt burdens.

The entire cycle takes about 100 to 150 years; the fifth phase of a cycle (decline) lasts for about 20 years.

The U.S. has gone through Stage 4 and is now in Stage 5:

- Assuming the U.S. entered its decline around 2008, this could continue out to 2130.

Stage 5 doesn’t have to be cataclysmic.

- The decline of the British Empire after World War II is a good example of the opposite, as is Japan’s deleveraging.

Conclusions

Ray Dalio is not your typical investor. But despite his massive success, his system is easy to understand, if not to re-create:

- He uses an automated system, based on macro fundamentals (very unusual)

- His has his own model of likely future asset correlations, based on economic history

- He reviews every mistake he has ever made, so that he can learn from it

It’s not easy for a private investor to replicate this approach. It would be possible – but time-consuming – to develop a macro-driven view on the major assets:

- stocks and bonds by geography (UK, Europe, US, Japan, APAC, Emerging)

- gold and oil

- major currencies (£, $, €, ¥)

That gives sixteen assets (Dalio insists on a minimum of fifteen) that can be traded long and short via spread bets.

Such an approach would be only for the brave. Those with a technical bent might adopt a similar strategy, but driven by indicators rather than fundamentals.

Probably the biggest lesson is about mistakes:

- write down the reasoning behind every position and every trade

- review how they worked out

- if they went wrong, work out why and how you can avoid it happening again in the future

Until next time.