Weekly Roundup, 15th December 2015

Today’s Weekly Roundup starts with the week’s big story – the Fed’s interest rate rise, covered in five articles in the Economist, and another in the FT.

Contents

Fed interest rate rise

The Economist leader and a second article took that view that what happens after the first rate rise for nine years is even more important. The Fed has to raise to retain credibility after promising to raise them for so long.

But although the US economy can probably handle a quarter-per cent rise, it can’t handle much more. So the Fed also needs to signal that it will be cautious in future.

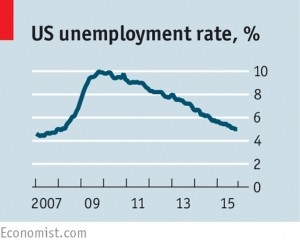

- unemployment is down to 5% and wage growth is picking up

- but consumer inflation is 0.2%, and core inflation – excluding food and energy – only 1.3%

The oil price fall will drop out of annual comparisons in a few months, so the consumer rate will rise, but core inflation looks stuck below its 2% target.

So a rate rise is not really justified, and another 1% (in four installments) during 2016 probably couldn’t be handled.

- The strong dollar and weakness in emerging markets, plus the loosening of monetary policy everywhere but the US, will all impact GDP growth in America.

- There is also the fact that with rates already near zero, it’s easier to raise them when inflation hits than lower them to fix deflation and recession.

Everyone who has raised rates since the 2008 crisis (the ECB, Sweden, Canada and Israel) has been forced to cut them again later. If the Fed tries to go too quickly, it will probably join them.

Buttonwood looked at the likely effect on markets. Higher interest rates should boost the dollar, and hurt equities and US bonds.

But as markets buy the rumour and sell the news, perhaps this has all been discounted already and the opposite will happen.

- The dollar is up 10% against the euro in 2015.

Generally the first hike in a tightening cycle doesn’t move markets much.

- The average move over 17 cycles since 1971 is a 1.1% rise in stocks over three months.

- Bonds generally do slightly worse than equities.

But this is not a typical tightening cycle. Interest rate rises usually combat three things:

- inflation, but there is next to none at the moment; the commodities slump may be due mostly to over-supply, but demand is also weak.

- an increase in risk appetite, but credit spreads (corporate bond vs government bond yields) are widening, which signals the opposite.

- growth in corporate profits, but these are now starting to slide after a long recovery

So normally the economy is doing so well that markets can shrug off the impact of tighter monetary policy.

Global markets have been subdued for the last couple of years, and reliant on central bank support (low rates make investors buy risky assets rather than hold cash):

- good economic news props up the markets directly

- bad economic news props up the markets indirectly, because central banks will inject more stimulus

After this week, good news from the US economy could mean more rate rises.

- If the Fed raises quickly, the impact on markets could be significant.

Bad economic news will mean the Fed has raised too soon.

- A global slowdown would need yet more stimulus to sustain equities, though bonds might survive.

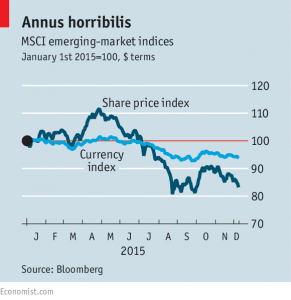

A fourth article looked at the likely effect on emerging markets (EMs).

- Rising rates in the US should make investors put their money there, withdrawing it from the EMs.

- Despite this many EM central bankers have been telling the Fed to get on with it.

The flows have already reverse from $22bn per month into EMs from 2010-14, to $3.5bn per month out right now.

- Further outflows would further weaken EM currencies, which in turn makes their dollar denominated debts become larger.

EM central banks could raise rates in tandem to protect their currencies, and many have already.

- Unfortunately this will hit domestic growth, and make it more expensive for firms to refinance domestically.

But perhaps the worst is already over.

- Exchange rates (excluding China) are back at 2002 levels, and the EM stock index is down 15% to its lowest since 2008.

But the golden age of EM growth – fuelled by China’s appetite for commodities – may also be over.

Future growth may be driven by America rather than China, which would only benefit Asian manufacturing countries that make things Americans want to buy. There’s no clear fix for commodity-led EMs.

The fifth article looked at the impact on the pound as rates fall in Europe but rise in America. Things could go either way.

Britain has done well as a safe haven as worries about the global economy grow.

- It could be the fastest growing large economy in 2015, and the pound has risen.

- With UK rates unlikely to rise before 2017, the pound may not rise much further.

But it’s possible that as cheap oil stops pushing down inflation, the BoE may change its mind.

- The Autumn Statement also predicted a reduced impact from the “austerity” cuts.

- Further rises would make imports cheaper and boost living standards.

But it would also make exporters less competitive, and hit the current account deficit (imports – exports), which at 5% of GDP is already the largest of any big developed economy.

- With foreign investment in London housing past its peak, financing this gap will become more difficult.

- Fear of a vote for Brexit in a 2017 referendum might drive down the pound and make things even worse.

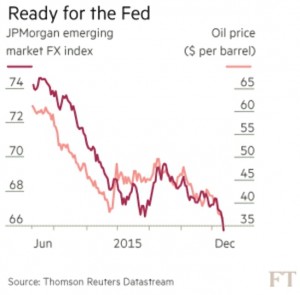

Over in the FT, John Authers argued that the Fed rate rise didn’t matter so much as the FX markets, OPEC and China.

John thinks that the stronger dollar has already done the work of the rate rise, by making imports cheaper and exports more expensive, pushing down inflation.

Similarly, when the ECB undershot QE expectations a few weeks ago, the dollar weakened 4.6% against the Euro. So FX markets do a lot of heavy lifting, and can have bigger effects than Fed rates.

Cheap oil also matters. Oil importers like India benefit, while exporters like Russia suffer. It pushes down US inflation but increases the risk of shale producer defaults. It also moves the markets.

And China matters. A renminbi devaluation exports deflation and hits emerging markets. No Chinese growth means even lower commodity prices. Both mean more to the global economy than a 0.25% rate hike in the US.

FTSE sectors

In the Chart That Tells A Story, Naomi Rovnick looked at the FTSE All-Share performance by sector. ((I couldn’t find a link to the article on the FT website, so I’ve had to scan in a clipping from my paper copy )) Not surprisingly, the oil, mining and industrial metals and minerals sectors have done worst, along with forestry and paper.

Commodities are on average trading at their lowest in more than six years and resources stocks are starting to cut their dividends (Anglo-American last week).

Apart from oil, which is a stand-off between OPEC and the US shale companies, the big problems are in iron ore, with massive over-production following the Chinese consumption boom up to 2011.

The anticipated interest rate rise by the Fed is another negative, as the dollar is expected to rise, pushing dollar-denominated commodities down.

Care home costs

Naomi also reported on care home costs. The cost of the average three-year stay is now £73K, and if you have more than £23K in assets – including your home – you have to find the money yourself.

This also applies if you have no money, but are deemed to have deliberately deprived yourself of funds (perhaps by spending your pension pot on a Lamborghini).

If you have less than £23K outside your house, you can defer the costs until you die, with an annual interest and administration charge of 2.25%.

It’s an anomaly within the NHS, which will completely fund treatment for cancer or a disability, but pay nothing towards dementia care, or simple assistance with daily living (food preparation or travel).

Care home costs have risen at more than twice the rate of inflation over the past 25 years, and further rises in real terms are expected.

The 2015 Tory manifesto included a pledge to “cap the amount you can be charged for your residential care – so you can have the dignity and security you deserve in your old age.”

But this cap (planned at £72K, now just below the average) has been delayed until 2020, by which time the new minimum wage will have increased care home costs still further. The plan to raise the assets ceiling from £23K to £118K has also been deferred.

It’s difficult to know what to do about this potential £72K cost in retirement. Should specific provision be made for it, or can it be safely ignored?

My instinct is to ignore it. When the time comes, you will either have £72K left in your pension / ISA pot, or you won’t:

- if you do, the government will make you pay for your own care

- if you don’t, you’ll have to sell your house

- if you’ve already burned through your property equity, then the council will pick up the bill for your care

It’s hard to imagine a savings strategy that would significantly change that scenario.

As you were, then.

What pensioners want

Merryn looked at a report from Retirement Advantage on what retired people want from their money.

- Number one is certainty – a guaranteed annual income every year forever. This would be an annuity, if rates weren’t so low.

- The main alternative is dividend stocks, and the oil / commodities bust has begun to show how much of the dividend flow comes from those stocks.

- The second priority for pensioners is flexibility – access to their money

- Annuities don’t fit the bill here, either

In fact, few things satisfy both requirements, since together they amount to having your cake and eating it too.

Probably the nearest options are:

- split your pot between drawdown and an annuity

- or my preferred option – which we looked at last week – start with drawdown and convert to a (much cheaper) annuity when you get to age 75

Merryn mentioned a third option: large diversified investment trusts that are now allowed to pay their dividends out of capital (which means they can be higher than the income from the underlying investments).

In general this approach is not a great idea, since there’s a risk that the fund will run out of capital eventually. CGT is also lower than high rate income tax, so some investors won’t favour the conversion.

But for trusts held in pensions, there’s no major impact, since all money drawn from a pension is treated as income already. So there’s the upside of potentially higher and more stable dividends with no real downside.

Merry recommends RIT Capital Partners and Personal Assets Trust – two diversified funds that are included in our own investment trust portfolio. But note that both yields are only around 2% at the moment.

Company cash hoarding tax

Vanessa Houlder reported that HMRC is considering bringing back a tax from the 1970s designed to stop companies “hoarding” tax.

- The thinking behind this is that any company not paying out all its income is aiming to convert it into capital, to be taxed at a lower rate when the company is eventually wound up.

These “apportionment” rules would mean that undistributed profits of “close” companies – those controlled by five or fewer people – could be taxed as though they had been distributed anyway.

- This is an extension of the IR35 legislation which taxes fees retained within personal service companies as if they have been paid out as salary.

The old regime led to many disputes as advisers tried to persuade HMRC that profits needed to be re-invested in the business.

- The rules were removed in the 1980s when Nigel Lawson brought CGT and income tax into line. But from 2016 the tax on dividends will be almost 10% higher than CGT.

- Ireland has an even bigger gap, and has already introduced a “close company surcharge”.

Vanguard smart beta funds

The Telegraph reported on Vanguard’s launch of what the newspaper called “Active ETFs”. They are basically smart beta, or factor funds.

There are four funds, all global and each charging a reasonable 0.22% pa:

- value

- momentum

- minimum volatility, and

- low liquidity.

All four are established factors for long-term equity outperformance.

Apparently the difference between a smart beta tracker and an active ETF is that the latter has a human manager sitting above the algorithm with the power to omit some stocks that meet the screen.

- I’m hoping that this is largely a marketing ploy which won’t be used too much in practice.

- As James Montier has pointed out, quant approaches seem to act as a ceiling rather than a floor, and manual tinkering seems to subtract rather than add value.

Smart beta has a lot of potential because the most popular indexing methodology at present – market cap weighting – is the worst possible method.

- Cass Business School in found in 2013 that market cap trackers were “buying into yesterday’s success stories”.

My only qualm about using these funds would be that a global approach – especially from a US firm – is likely to overweight US stocks from the perspective of a UK investor.

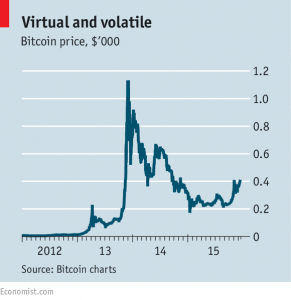

Bitcoin not splitting

Finally, the Economist reported on the “Scaling Bitcoin” conference that took place last week in Hong Kong (most BitCoin miners are now from China).

It was designed to end the dispute about how to expand the capacity of the Bitcoin system.

- it can only 7 process transactions per second, compared to many thousands by the major credit cards

A group of Bitcoin developers had suggested allowing bigger “blocks” – batches of transactions – to be processed, using a new version of the software (Bitcoin XT). This has not been widely adopted.

The conference decided to prioritise other technical fixes to boost capacity, with an increase in block size from 1Mb to 4Mb as a second stage.

- Increasing block size may be difficult because all the computers in the network need to upgrade their software at the same time.

Even if this fix works, resolving future problems will be no easier. A decentralised currency is by design difficult to govern.

Books of the year

And finally, finally – a quick plug for our Books of the Year, which you can find here. There’s still time to buy one (or more) before Christmas.

Until next time.