Secrets of Sand Hill Road #4 – Boards and Deals

Today’s post is our fourth visit to Scott Kupor’s book Secrets of Sand Hill Road.

The Board of Directors

Chapter 10 of the book sticks with Term Sheets, but instead of finance, it focuses on governance.

- The board of directors is the key player here, and so who is on the board, and which issues they can vote on, is very important.

The biggest thing that the board does is to hire and fire the CEO.

- This is reason enough for the founder (who usually wants to be CEO) to pay attention to the composition of the board.

Scott notes that most people prefer an odd number of board directors, to avoid deadlocks.

His example term sheet has three directors, one of whom is from the Series A VC, representing the preferred shareholders.

- There may be multiple Series 1 investors, but usually, one will be the lead investor (often with 50% of the money) and will take the board seat.

The second seat represents the common shareholders and goes to the CEO (which is usually the founder, to begin with).

- Sometimes this seat is reserved for the founder, but many VCs would oppose this reservation.

The third seat is for an independent director (not an investor nor an officer).

- They will need to be approved by the other two directors.

Some founders have insisted on having what’s called a “common-controlled” board, meaning that there are more board members representing the common shareholders than other classes of shareholders.

This prevents the VCs from firing the founder and is the source of many recent Silicon Valley governance issues (eg Uber).

On the other hand, further financing rounds may lead to more VC seats.

- In which case the common stock may also be granted balancing seats.

Role of the Board

Here are the main duties:

- Hire and fire the CEO

- this is why board composition is so important

- Provide guidance on the long-term strategic direction for the business

- this includes budgeting and financing (including capital raises)

- Approval of corporate actions

- financing, acquisitions and divestitures, compensation levels, size of the options pool, the market value of the stock for options purposes (usually via an external “409A” opinion)

- Governance and compliance duties

- hold regular board meetings etc.

- VC-specific duties

- coach the CEO, exploit the VCs network

Not the Board’s role

The key thing that the Board shouldn’t be getting involved in is product strategy (the CEO’s job).

- Which means in turn that the CEO needs to learn how to manage the board (including running the meetings).

Private versus Public Boards

For public companies, board members are typically elected by the common shareholders.

Indeed, most public companies have no preferred shares (Google and Facebook are notable exceptions).

- Which means all shareholders have a common interest.

Nor do public companies have the protective provisions associated with VC preferred shares (see below).

- And anti-dilution and liquidation preference terms are also unlikely.

This makes it easier in principle to obtain approval for things like acquisitions and fund-raises.

Dual Fiduciaries

VCs are dual fiduciaries.

As a board member, a VC has a fiduciary duty to the common shareholders of the company.

They need to act (vote) so as to maximize the long-term value of the common stock.

But as a GP in a venture capital firm, she is also a fiduciary to her LPs.

The VC also needs to maximise the value of his LPs’ investments.

- This can lead to a conflict of interests under certain conditions.

Term sheet governance

Protective Provisions

Delaware law governs the default voting for corporate actions (most startups are incorporated in Delaware because it has the most well-developed set of laws and legal opinions on corporate governance and shareholder rights).

I always thought there were tax breaks, but apparently not.

- The protective provisions in the term sheet act as an overlay to Delaware law.

The first provision will be to lump all Preferred series into one voting pool so that VCs don’t end up blocking each other.

- This might be varied if a late-round VC invested a lot of money at a high valuation for a low ownership share – under those circumstances, the late VC would require extra protections (effectively a veto on deals).

- An alternative is to used supermajorities (voting thresholds) rather than simple majorities.

Votes that protective provisions cover include:

- new classes of stock

- corporate actions (sales and acquisitions)

- liquidation

- recapitalisation (refinancing to change the capital structure)

- increases in employee stock options (dilution)

Registration Rights

Our term sheet takes a bit of a shortcut by saying that VCF1 gets “customary registration rights.” Luckily for practitioners in the field, they understand what that means.

This is to do with registering shares with the SEC prior to an IPO.

Pro-Rata Investments

This is an anti-dilution provision to allow VCs to invest their “reserve dollars” in future financing rounds.

- It’s often restricted to “major investors” ($2M+)

This can be an issue when VCs require a certain percentage of a firm because they can only handle sitting on around 10 to 12 boards at one time (as well as wanting to move the needle on their fund through large investments).

Stock Restrictions

There are a couple of these, on those who hold at least 2% of the stock:

- right of first refusal (ROFR) – the company has the option to buy any shares at the price offered by an external third-party

- this can also be seen as a veto on undesirable third parties

- co-sale – this is the opposite of ROFR

- if one shareholder sells outside, all other shareholders must be given the same deal (pro-rata to the proportion of share being sold by the first holder)

These provisions are really designed to stop founders from quietly selling out.

- The VCs are investing in the founder as much as in the startup.

Sometimes the VCs themselves are bound by the same restrictions, and sometimes it’s just the common stock-holders.

Drag Along

This prevents minority investors from holding out on a deal to try to get a better deal for themselves.

- When all the major shareholders agree on a deal, the minority shareholders (still above 2% share) are forced to take part, too.

Normally the board, the Preferred and the Common each need separately to agree the deal.

D&O Insurance

This is protection for the startup’s board members and officers against legal liability.

- VC partners will have this already from their VC firm, but they get it again.

Vesting

The term sheet will include the vesting rules for the founder and employees.

Employees usually get 25% after a year and the remaining 75% monthly in 1/36th tranches for the next three years.

- They also usually have to exercise options within 90 days of leaving the firm (“cashless exercise” facilities are usually provided, but any tax liability was immediate until 2017 when a 5-year deferral was introduced).

- Some firms now offer up to 10 years to exercise options, but this means that the tax-exempt ISO options ($100K per year) are not available.

Founders also normally vest over four years, but the start date can be a bone of contention.

- VCs would like the start date to be the date they invested, but founders want to start from when they founded the company, which may even predate incorporation.

- Compromise is required here.

The other dispute is what happens on an acquisition.

- Founders want to vest, but an acquirer may want to still have a lever over the founder’s behaviour.

- A common solution is a “double-trigger” – acquisition followed by termination of the founder will accelerate the vesting of the founder’s shares.

Employee Agreements

All employees and consultants will be required to sign non-disclosure agreements and to assign all IP to the company.

No-Shop

There is a gap of between two weeks and a month between signing the term sheet and closing (when the VC wires its money to the company).

- This is similar to the house-buying process in England.

Since either party could walk away in this period, there is usually a 30-day tie-up during which the terms of the deal sheet cannot be disclosed, and the startup can’t shop around for a better deal.

Deals

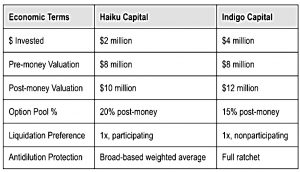

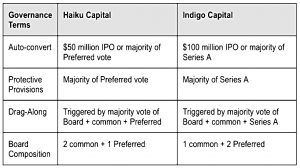

Chapter 11 compares two deal offers.

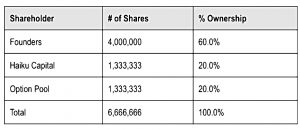

Cap table

The first step in the comparison process is to create capitalization tables (cap tables) which show the post-money ownership structure.

The two deals result in an 8% difference (delta) in founder ownership.

- Indigo invests more and ends up with 13% more ownership.

- Haiku takes an extra 5% from the owners for the option pool.

So the first question is whether the startup can make use of the extra $2M from Indigo before the next fundraising round (in one to two years).

- Would the money make it more likely that you will hit the milestones needed to reach Series B?

- Or even to reach a more advanced set of milestones (which would justify a higher valuation in the next round, and a lower Series B dilution)

Does either of those potential benefits outweigh the extra dilution upfront?

You want to think about the funding amount that gives you the highest degree of confidence in being able to maintain momentum from one funding round to another.

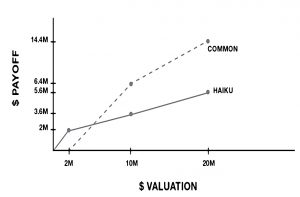

Payout matrix

The next step is to build a payout matrix for each offer.

- This shows how proceeds are divided between preferred and common at various exit valuations.

Haiku has participation in the common on as well as redemption of its preferred.

In contrast, above an exit price of $12 million, Indigo will choose to convert its preferred shares to common shares and take only its 33.3 percent of the proceeds that equals its level of economic ownership.

So the extra dilution from Indigo might be worth it if you expect a high sales price.

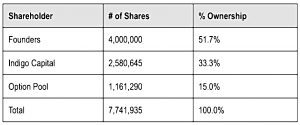

Down round dilution

The third economic step is the anti-dilution protection in any subsequent down-round financing.

- The amount of protection that the VC receives can be broad-based weighted average (Haiku) or a full ratchet (Indigo).

- The Haiku arrangement is friendlier to the common shareholders because it weights the adjustment by the relative size of the new financing round.

To examine the impact, Scott imagines a Series B from Momentum Capital of $2M at a $6M pre-money valuation.

- This is lower than both Series A offers so the protection would kick in.

The initial prices per share being proposed by Momentum are about ninety cents (had we been in Haiku land) and seventy-eight cents (had we been in Indigo land).

The different prices reflect different numbers of shares outstanding.

Momentum wants to invest $2 million and own 25 percent of the company, [but] the antidilution protection [means] that the company needs to issue more shares to [the Series A VC], which dilutes the ownership of Momentum.

So calculating the impact is an iterative process.

Here is Scott’s Series B cap table for Haiku (the Indigo table is missing from my copy of the book):

The founders’ ownership differs by more than two times between the two options.

In practice, Momentum would make its deal contingent upon Haiku/Indigo (particularly Indigo) waiving its antidilution protection, or at least modifying it to a broad-based weighted average. Momentum is unlikely to want to fund the business if it believes that the remaining team is not adequately incented.

Governance

The final step is to compare governance terms.

There is no rule that says that all subsequent investors get the benefit of the same terms as did earlier investors, but in my experience this is often the starting point of the discussion.

Haiku has used capital “P” Preferred in its voting thresholds, whereas Indigo has used Series A preferred only. While it’s impossible to fully know the implications of this downstream, in general it’s simpler to have a capital “P” Preferred vote.

Haiku is proposing a common-controlled board. Indigo is less founder friendly in this regard, proposing that it get two boards seats to only one for common.

Scott concludes:

There are pros and cons to every deal, and there usually is no definitive right answer. Some of the decision depends on how confident you are in the company’s future and how much you are willing to gamble on the downside in order to give yourself more upside.

That’s it for today.

- We’re 80% of the way through the book, with one more article to come, plus a summary.

Until next time.