Smarter Investing 3 – Smarter Portfolios

Today’s post is our third look at Tim Hale’s book Smarter Investing. The section we’re going to look at today is called Smarter Portfolios.

Contents

- Smarter Portfolios

- Risk

- Risk-free assets

- Stocks and diversification

- Theoretical framework

- Portfolio construction

- Tobin’s Separation Theorem

- The big questions

- Global diversification

- Emerging markets

- Small and value companies

- Other return assets

- Currency exposure

- Tim’s return engine

- The defensive mix

- Which portfolio?

- Conclusions

Smarter Portfolios

Tim breaks this section down into three:

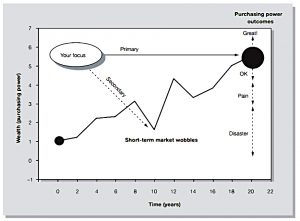

- risk – you need to take on some risk to meet your financial goals

- portfolio construction – in which Tim aims to put together a “portfolio for all seasons”, or rather six of them

- portfolio choices – in which the character of each of the six portfolios is examined in depth

Risk

Tim defines risk as:

The probability of an adverse event (hazard) happening, and the effect of this exposure dues to a specific hazard on you.

That’s reasonable but complicated.

- A simpler version is: risk = probability * impact.

- It’s like the opposite of expected returns, which is size of gain * probability of gain.

The struggle with risk – as with so much else in investing – is to bring your slow thinking system to bear, rather than the emotional fast system.

- The problem is that the fast system evolved to deal with complex, urgent situations where we have imperfect information – such as investing.

- So it needs a conscious effort to overrule it.

Risk is important in investing, for two reasons:

- it’s closely associated with reward (returns)

- we can’t control the future, but we can put together a plan that minimises the impacts of the risks we identify.

Risks in investing include:

- market (price) risk – from the assets you choose to hold

- interest-rate

- liquidity

- currency

- counterparty

- agency (managers and advisers)

- inflation

And the possible solutions are:

- accept (take)

- avoid

- mitigate (reduce)

- transfer (to someone else, usually at a cost)

Risk-free assets

We sometimes have a risk-free asset in the UK, in the form of National Savings index-linked certificates.

- These are backed by the government and have always repaid more than the inflation rate.

- This protects your purchasing power, though it usually doesn’t increase it by much.

I have held these before as a small part of my portfolio.

- They aren’t always on sale, however (they aren’t at the moment).

There are two alternatives that sound risk-free, but aren’t:

- bank deposits – these are guaranteed to £75K / £85K, depending on the exchange rate with the euro, but they often don’t keep up with inflation

- index-linked UK government bonds (gilts) – these protect their interest against inflation, but the sale price of your bond depends on the market and on interest rate movements

To get a better return than these low-return investments, we need to take on other risks.

Stocks and diversification

Shares provide the highest long-term returns, but investing in an individual share is very risky.

- Each company has it’s own specific risks, arising from the nature of its business.

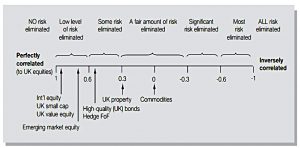

The more companies you invest in, the more you reduce these individual risks.

- With somewhere between 30 and 50 stocks, you have eliminated all of the company-specific risk, and are left with just the risk of the market that the stocks come from (say the FTSE All-Share).

- So there’s usually no benefit in holding more than 50 stocks. (( In a single portfolio – you may run multiple portfolios for multiple reasons, and decide that you need 30 to 50 stocks in each of them ))

- The remaining market risk is known as systematic risk.

Note that holding 50 stocks doesn’t mean that you will get the market return.

- Most stocks deviate from the market return by more than 10% each year.

- The only way to get (almost) the market return is to buy an index tracker.

- But with 50 stocks you will probably end up reasonably close.

Theoretical framework

The theory of stock risks (from Sharpe, then later Fama & French) is that various factors increase the riskiness of stocks, and investors demand compensation (higher returns) for these risks.

There are three main risks for stocks:

- market risk (of holding a stock vs cash)

- size (smaller companies are riskier)

- value (less healthy companies should be cheaper to buy, and return more over time if they don’t go bust)

For bonds, the risks are:

- the interest rate (short-term rate on risk-free debt to the government)

- inflation expectations

- the issue period, or maturity (longer is riskier and more volatile, mostly because interest rates and inflation might change)

- the counterparty (credit risk, of not being repaid – this is rated by credit agencies as AAA, BBB etc.)

- liquidity risk (some types of bonds may be harder to trade)

- structural risk (bonds may have features that favour the borrowing entity over the investor)

Since you are less likely to be buying individual bonds, these factors need not concern you so much as the equity risk factors.

Portfolio construction

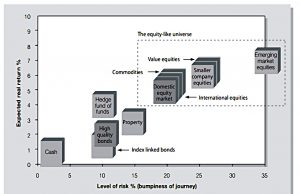

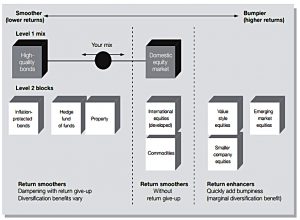

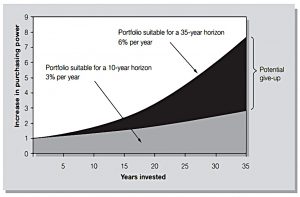

The basic problem is that equities provide the best returns, but are also the most volatile / risky.

Anything we add to the portfolio needs to do at least one of three things:

- provide similar but uncorrelated returns to the market (say the UK All-Share index)

- increase returns, or

- lower risk and volatility

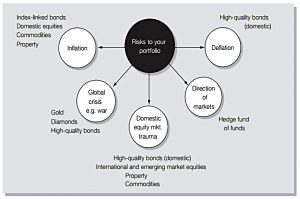

Note that different assets will protect against different risks (inflation, deflation, crash / flight to quality).

On top of this, we need liquidity, low costs and tax efficiency.

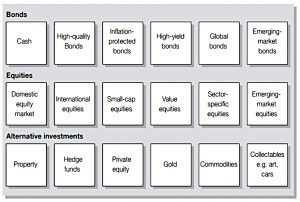

Things that we might look to add therefore include:

- higher returns – value stocks and small companies, emerging market stocks

- uncorrelated returns – international stocks, property, commodities and gold, hedge funds, private equity

- risk protection (defensive assets) – bonds (including index-linked bonds) and cash

Note that Tim excludes many of the uncorrelated returns assets, for reasons that aren’t clear to me at this stage.

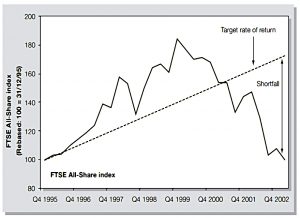

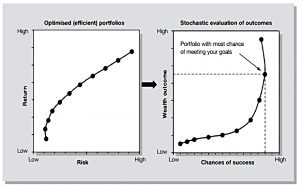

The overall aim is to ensure that we take the smoothest possible path to where we want to get to, without giving up so much return that we fall short.

Tobin’s Separation Theorem

Tim comments briefly on James Tobin’s Separation Theorem, which suggests that the most efficient portfolio – in risk-reward terms – is the market portfolio – all the investable assets in the world. (( Note that not all these assets may be investable to the UK private investor ))

- To reduce the risk of this portfolio, you convert some of it to cash.

- To increase the returns you add leverage (borrow money to buy more of the portfolio).

Weighed against the market portfolio, most investors are overweight in stocks.

- My own interpretation of this is that Tobin’s portfolio is ideal for people who are already rich.

- Most investors need to get richer before they get old.

So they need to take on more risk.

- A higher equity allocation probably makes more sense than leverage.

The big questions

Tim boils portfolio construction down to five questions:

- should you diversify globally?

- should you hold emerging markets?

- should you hold small companies and value stocks?

- should you hold the other uncorrelated return assets (property, commodities, private equity etc.)?

- should you accept currency risk?

Global diversification

Many investors hold just UK stocks.

- Even though the FTSE-100 in particular is home to many companies with significant foreign earnings, this is a serious home bias compared to the 7% to 10% of equity markets that the UK exchange comprises.

- At the other end of the spectrum is the world portfolio, which substitutes UK bias for US bias, since the UK markets make up 40% to 50% of global stock markets.

You can of course choose some point in between.

- I personally use a 50% UK equity, 50% international equity approach.

- I think that familiarity with UK stocks – and their greater suitability for active investing – outweighs the risk of a long-term UK market downturn. (( This has never happened in the UK, though clearly Japan has now had two lost decades ))

Using the heuristic that even weights work out best in the long run, I then divide the international equity portion as follows:

- 25% Europe

- 25% US

- 25% Asia (split between Japan and APAC)

- 25% emerging markets (with a specific allocation to China)

Emerging markets

Tim suggests 10% to 20% of the growth (equity) portion of the portfolio should be allocated to emerging markets.

In practice, UK investors working towards financial independence will have around 25% of their wealth in property.

- Those living in London will have more. (( I had 36% in property at the start of 2017 ))

So the growth part is a maximum of 75% of the total portfolio.

- If you subtract 20% for bonds / cash, we can round the growth portion down to 50%.

- Which leads to a total allocation of 5% to 10%.

I’m just about on track here, with a 5% allocation.

- I have a lot of cash at the moment.

Small and value companies

Tim wants at least 10% in each of small and value companies (of the growth portion, as far as I can tell).

This would require a fair amount of work internationally, thought it would be easy enough in the UK.

- So I’m trying here, but probably not keeping up

- I probably have around 10% in total between the two factors (which is more than 15% of my growth assets)

Other return assets

Tim is against these in general, though he allows 10% of global commercial property.

- As previously discussed, I have a lot of (residential) property, and hence much less in terms of other return assets than I would like.

- I would split my 10% across all the types of asset (property, commodities and gold, hedge funds, private equity)

Currency exposure

We’ve seen the importance of currency during 2016, when sterling fell 20% after the Brexit vote.

- Those with internationally diversified portfolios will have done well, as foreign stocks rose in response.

- To be fair, the FTSE-100 also did well, on the back of foreign earnings.

My own take on currencies – and Tim’s take too – is that:

- they are uncorrelated to UK equities

- they even out in the long run (they move back towards purchasing power parity – as used in the Economist’s Big Mac index that we’ve discussed several times).

So long-term, well-diversified investors can safely ignore currency risks.

- Tim makes an exception for non-UK bonds, but I’m unlikely to ever hold enough of these (5% max) to make a massive difference.

Tim’s return engine

Tim’s final allocations to the growth part of his portfolio are:

- 45% developed markets

- 30% smaller companies and value stocks (developed)

- 10% emerging markets

- 5% emerging markets style tilts

- 10% global commercial property

I think this is a reasonable starting point, but everyone needs to put their own stamp on this.

- Tim also offers eight alternatives, called simple, broad, diversified and tilted, each with a home or global bias.

Tim’s return engine stacks up well against UK and global equities for his chosen period of back-testing (1989 to 2012).

The defensive mix

Tim chooses UK gilts for most investors, substituting index-linked gilts (short-dated) and NS&I savings certs, plus cash for the more cautious investor.

The final step is to combine the return and defensive assets.

- Tim offers breakdowns for six combinations in 20% steps of return assets (from 0% to 100%).

Which portfolio?

To decide which of the six portfolios is appropriate for you, he recommends starting with a risk profiling questionnaire.

- You can take ours here.

Factors that you need to balance when choosing the best portfolio include:

- your risk tolerance

- your need to take risk (to meet your goals)

- your financial capacity to take losses

- your investment time horizon

Tim then provides detailed analysis of the six portfolios, which we won’t go into here.

- To be honest, I found the tables (a full page of numbers for each portfolio, plus a full-page summary table) somewhat off putting.

Conclusions

There’s little to argue with in this section of Tim’s book

- But it is very long-winded and repetitive.

We’ve covered another 50-odd pages today, and are now around 60% of the way through.

- So we should have another two articles remaining.

What have we learned today?

- Risk is important:

- it’s associated with returns

- we can’t control the future, but we can minimises the impacts of the risks we know about

- Stocks give the highest returns but are the riskiest

- bonds and cash (the defensives) and other return assets (property, commodities and gold, hedge funds, private equity) can be used to diversify and protect our portfolio

- Portfolio construction boils down to five questions:

- should you diversify globally?

- yes, to whatever extent you feel comfortable with

- should you hold emerging markets?

- yes, at least 10% of your growth assets

- should you hold small companies and value stocks?

- yes, at least 10% each of your growth assets

- should you hold the other uncorrelated return assets (property, commodities, private equity etc.)?

- yes, to whatever extent you feel comfortable

- should you accept currency risk?

- yes, in the long-run it’s a wash

- should you diversify globally?

- To choose your mix of growth and defensive assets, consider:

- your risk tolerance

- your need to take risk (to meet your goals)

- you financial capacity to take losses

- your investment time horizon

I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with section four of Tim’s book, which is called “Smarter Implementation”.

Until next time.