Excess Returns 12 – Risk Management

Today’s post is the penultimate article in our long series on the book Excess Returns, and looks at risk management.

Contents

Risk Management

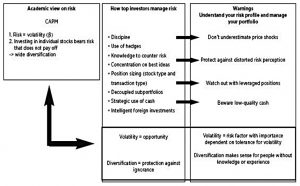

In Chapter J of his book Excess Returns, Frederik Vanhaverbeke looks at risk management.

- We’ll ignore the problems with the classical view of risk as equivalent to price volatility for now (see Volatility is not Risk for more details)

- We begin instead with the traditional trade-off between risk and return.

The conventional view is that risk and return are linked, and you can only achieve high rewards by taking on a lot of risk.

- This leads to the approach of working out what your risk tolerance is, and using that to determine your asset allocation.

The big decision is what proportion of equities to hold, since they are the asset with the best returns and the highest price volatility.

Equities

You can take our Risk Tolerance Questionnaire here, but a useful shortcut is to imagine a 40% decline in equity prices.

- You should live through this two or three times in a long investing career.

Next, work out what kind of a hit to your portfolio you can take without panicking and hitting the sell button. (( You won’t really know until you are tested, but give it your best shot ))

Then work out from that what proportion of equities you can tolerate.

- For example, if you can take a 20% drop in wealth, you can hold 20% / 40% = 50% in equities.

Academic theory

This “risk equals return” approach comes from the academic view of risk in the efficient market theory and the Capital Asset Pricing Model

Here, returns have three components:

- The risk-free rate of return (on government bonds)

- The systematic risk of a stock

- this comes from its historic volatility and correlation to the overall market return (beta)

- the market return is usually positive, but may be negative for a period

- The abnormal return from non-systematic risk

- this is the company-specific risk

- it is assumed to be random and impossible to estimate, with a zero mean

Portfolios are constructed to eliminate non-specific risk through diversification.

The theory produces some interesting results:

- systematic risk comes from historic volatility, and therefore the higher the volatility, the riskier the stock

- riskier stocks produce higher returns

- riskier portfolios produce higher returns

- investing in individual stocks is pointless, since company-specific risk can’t be estimated and there is therefore no reward on average

Frederick finds the theory to be mostly intuitive:

- higher returns should require more risk

- volatility indicates problems with price-setting, implying uncertainty as to the intrinsic value of a stock

- volatility is a real risk / problem for investors using leverage, for short-term traders, and for those with low risk tolerance

Problems with theory

Frederik’s two main criticisms are:

- markets may not always be efficient (quite a fundamental one, this), and

- historic volatility may not predict future volatility

My own problems with the EMF and CAPM are a level deeper.

- They take no account of human psychology and emotion (behavioural finance) which explain why markets are not efficient in the short to medium term.

There’s also the practical problem that high-volatility stocks don’t outperform over the long term.

- In fact the evidence points slightly in the opposite direction.

Risk

More fundamentally, as mentioned above, Voliatility is not Risk.

- For one thing, who cares about upside volatility?

Frederik agrees with Buffett, who defines risk as the probability of a permanent loss of capital.

Top investors

Top investors (specifically, the top value investors that Frederik’s book focuses on) are only interested in two things:

- price, and

- (intrinsic) value.

Risk does not come from volatility, but from an incorrect assessment of the gap between price and intrinsic value.

They think in company-specific terms.

- Whereas the CAPM says that it’s impossible to know about company-specific risk, and therefore pointless to invest in individual stocks.

For smart investors volatility is not risk but opportunity. They buy stocks that trade below their intrinsic value and sell when they trade above that value.

It would be silly for an investor to assume that a stock that has lost half of its value would be riskier at the much lower price (because of the higher volatility due to the previous price drop) than at twice that price (before the price drop).

Risk mitigation

Top investors mitigate risk through:

- due diligence

- a focus on a circle of competence

- a margin of safety (discount to intrinsic value)

- avoiding firms without pricing power, subject to regulation, dependent on weather conditions, or too dependent on a single customer

- avoiding hot stocks or industries

- sticking with their strategy through temporary underperformance

- avoiding trades that could wipe them out

- avoiding leverage

Portfolio concentration

Top investors (stock pickers, not quants) use far more concentrated portfolios than typical retail investors.

- Many have the number of large positions in single figures, and will take single positions of 20% to 40%

- Don’t try this at home.

Position size

Top investors take smaller positions in businesses that are harder to evaluate, that are less stable, that still have to prove a lot, or that are exposed to more outside risk.

Companies with high visibility deserve a higher weight in a portfolio than those with poor visibility.

Sub-portfolios

Many top investors approach diversification from the opposite direction, by using five or more sub-portfolios (which may themselves be concentrated) that are not correlated with one another.

Special situation stocks, turnarounds and distressed debt can offer excellent diversification as they are event-driven.

Arbitrage positions also produce stable returns. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) tend to track real estate prices.

Cash

Cash is a drag on returns in bull markets, but many top investors hold significant amounts at all times:

- this reduces volatility

- and it acts as “dry powder” when something bad happens

Conclusions

This is one of the shorter chapters in the book, and it has less new content than most.

- Frederik provides a handy summary diagram:

Theory says that risk is volatility, and there is no compensation for the risk of picking individual stocks.

- Top investors see volatility as the opportunity to buy and sell at attractive prices.

- They reject diversification as a protection against ignorance.

- They rely on knowledge and discipline, and concentrate on their best ideas.

- They use debt sparingly and store their cash safely.

I can agree with most of this – particularly the sub-portfolio approach – but we’re not all Buffett, and a concentrated portfolio of a few stocks is not recommended.

- For the typical DIY investor aiming for financial independence, active stock picking makes sense for only a small part of your portfolio (let’s say 10% to 30%).

If you want to be concentrated (less than 20 stocks) in that part of your pot, go ahead.

- But otherwise, asset allocation and diversification remain your friends.

I’ll be back in a few weeks with the last chapter of the book, which is called The Intelligent Investor.

Until next time.