Excess Returns 13 – The Intelligent Investor

Today’s post is the thirteenth – hopefully not unlucky – and final article in our long series on the book Excess Returns. Chapter K is called The Intelligent Investor.

Contents

The Intelligent Investor

In the long run, the majority loses. To win you have to act like the minority. – William Eckhardt.

In the last chapter of his book Excess Returns- Chapter K of his book , Frederik Vanhaverbeke looks at “The Intelligent Investor”.

- This is, of course, a reference to Ben Graham’s famous book of the same name on value investing.

Frederik’s chapter is partly a look at the personal qualities of successful investors and traders, and partly a summation of the ideas Frederik has unearthed throughout the book.

He calls these “soft skills”, but for me that is a misnomer, for his three top-level categories are:

- a strategy (an “edge” that identifies a market inefficiency), applied in a consistent and disciplined way, within a circle of competence

- a process, “characterised by independence, hard work, eternal study, discretion and knowledge”

- character – “modesty, passion, patience, emotional detachment and the courage to go against the crowd”.

These are not soft skills – the attributes that enable you to interact effectively and harmoniously with other people – at all, but rather hard ones.

- To these Frederik adds “experience, talent and intelligence”.

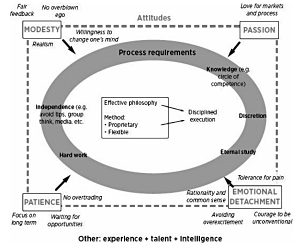

Frederik supplies a summary diagram to show how these elements interact, but as is often the case, it is more likely to confuse than illuminate – at least until you have read the chapter.

Strategy

Frederik divides strategy into two:

- philosophy

- execution

This is all about being consistent and not giving in to temptation.

- The strategy must fit the investor, so that they stick with it.

- A good fit also leads to a higher motivation to do the necessary work.

Frederik’s allows for separate philosophies for investing and trading.

- But since his focus is on investment, and his central investment thesis is that excess returns come from a value orientation, his core investment philosophy is one that identifies stocks that are mis-priced.

I think that there are many ways to skin a cat, and while identifying “mis-pricing” will be an objective for investors of all stripes, what they mean by it is different.

- Momentum and growth / quality investors will be very much focused on the future, and happy to buy even if the current price is higher than the current value.

There’s more on philosophies in our first article on the book – see here.

Execution is about the method used for timing purchases and sales, and can differ between investors with the same philosophy.

- This is because the method has to be compatible with the investor’s personality and experience.

- This will prevent them from over-riding the system in times of stress.

For Frederik, execution includes:

- the type of stock targeted

- long vs short

- use of leverage (if any)

- time-frame for the investment

Investors must know themselves in order to understand what strategy matches their personality and interests. Intelligent investors therefore closely monitor their feelings and actions over several market cycles.

A recurring theme among top investors is their belief that the simplest and most focused strategies are the most effective.

The strategy must be sufficiently dynamic and flexible to deal with a world where inefficiencies come and go. Specialisation in one particular sector is ineffective.

The servile and thoughtless imitation of the strategy of a great investor is seldom a good idea.

The very best investors stick to their guns when times are hard.

Some great quotes here, but I don’t entirely agree with the last one.

- Sometimes value investing (for example) works, sometimes it doesn’t.

- The not working periods can last for a decade or more, and you would be well-advised to do something different in the mean-time.

There’s nothing wrong with buying growth stocks – or momentum trading – during a bull market, so long as you know that:

- that’s what you are doing

- it’s a temporary thing

- you must use good risk management and not too much leverage

- you have to keep on eye on the exits.

Process

For Frederik, the first element to process is detailed knowledge, of both your strategy and your individual positions.

Knowledge provides a competitive advantage over less informed market players.

I can’t agree completely with this one, either.

- Focused investors with few positions (let’s say 12 or fewer) will definitely need to know as much as they can discover.

- But it’s just as possible to do well with larger portfolios employing a more statistical approach.

The investors who really shine – and I think they are rare – are those who can take very large positions that they really believe in (probably on the basis of significant research), and can then abandon them when new facts come to light, or the price action doesn’t follow their expectations.

- In my experience, most private investors who have great knowledge of the companies they hold become too attached to sell them.

Frederik also recommends other approaches to knowledge that are easier to support:

- accounting and business knowledge

- a “circle of competence” – industries and companies where they have special expertise

- experience and “unconscious competence”

Besides knowledge, Frederik stresses the importance of independence.

- We’ve touched on this when we said Cut Out The Noise.

Discount what is already known and look for unique information that can make a difference.

Following the advice of others who seem to be knowledgeable conveniently allows the market operator to put the blame on others if things don’t work out.

The best opportunities in the market are rarely found in places that many others have already identified as attractive.

Reliance on others makes the market operator extremely vulnerable to all kinds of external stimuli that can throw him off course.

He notes that several top investors (Buffett, Templeton) moved (physically) to places far away from the chatter and noise.

Frederik’s third element of process is hard work.

- It’s not physically hard work, of course, but the devotion of many hours a day to reading and analysis.

He links the hard work to:

- passion (for the markets)

- intellectual curiosity

- putting the hours in

- Frederik says “full-time”, but that’s a moveable feast

- I think you can do pretty well on 20+ hours a week

- But then I’ve been doing this for 30+ years

- Beginners probably need to work harder at first

Closely related to hard work is what Frederik calls “eternal study”.

I take this one for granted these days, because the markets have changed so much during my adult life.

- But from the mid-80s to arguably the 2008 crash, and definitely to the 2000 crash, not much changed, and there wasn’t much new to learn.

- 2008 was a wake-up call for me, and I went back to basics.

But the markets are like the weather.

- There’s something different – and something to learn – every day.

Another key point that Frederik makes is that it’s important to learn from your own personal investment mistakes.

- Keep a trade log, or diary and try not to do the same thing wrong twice.

- Work out what would have happened if you had done something different.

Frederik links learning with the personal attributes of modesty, humility and responsibility.

- I’ve survived without the first two, but it’s important to be realistic about what is down to you, and what is “bad luck”.

- Don’t blame others, and don’t think that you know everything (which is not the same as thinking that you don’t know enough to do well).

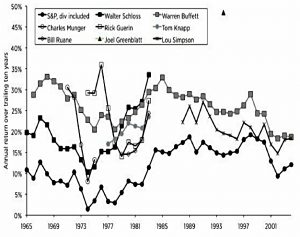

You should focus on your long-term returns.

- Ten years beats this year, and this year beats this month.

- Forget about today, and this week – short-term returns are random.

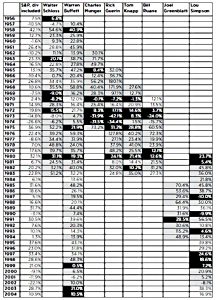

Even the best investors underperform sometimes.

Frederik’s final element in process is discretion.

He gives two reasons for not telling people about your positions and opinions:

- it puts psychological pressure on you to keep holding them

- it can move the market (if you are famous and respected)

The second is a red herring to me, since even if you were in such a fortunate position, the market would move in the direction that you want (unless you blab before you have finished building your position).

I personally now keep quiet (( This website excepted, of course )) for a different reason:

- In the age of social media, all opinions are considered equal, and defending my views against the less knowledgeable puts me in a frame of mind that is not compatible with good investing. (( I’ve actually had surprisingly little success over the years in persuading friends and family to take my advice ))

Character and attitudes

The third leg of Frederik’s “Intelligent Investor” is character.

- He starts with modesty, and a lack of ego and arrogance.

I think he’s only telling part of the story:

- both ends of the spectrum are counter-productive.

- so let’s dig into the detail.

Frederik says that:

- arrogance can lead to overconfidence and greed

- this can lead to behaviours like not taking a loss, picking tops, not learning from mistakes

- arrogance can lead to unrealistic expectations (of returns and win ratios), performance-chasing and overreach

- arrogance can lead to taking too much risk in bull markets and not enough in bear markets

- arrogance can mean not looking at your trades from all angles (ie. understanding the bear case)

- you need to be able to get out (or even reverse) if the bear case looks proven

Well, I agree with all of those, so it looks like Frederik and I have different definitions of humility and arrogance.

Frederik concedes that confidence – to think independently, for example, or even to take a trade in the first place – since you are saying that the person on the other side is wrong – is important.

- So it’s just semantics really – one man’s confidence is another man’s arrogance.

Next up is passion – about the markets and the investment process, rather than about making money.

- Money is just how we keep score, but at the same time, it’s important to keep score.

Those focused on money will look for shortcuts.

The third desirable personality trait is emotional detachment.

- Here’s one where I think I was at the front of the queue.

- Not much gets me emotional. (( Apart from football ))

I think one of the big factors here (for me at least) is a long-term orientation.

- It’s hard to get worked up about a good or a bad day when you’re always looking twenty years into the future.

I try to think of positions as just numbers in a spreadsheet, and don’t like to get know people at the companies.

- The only exception to this rule is startup investing, where the character of the founders can make such a difference.

- Once the company is profitable, let the numbers speak for themselves.

And I don’t check stock prices every day.

- My whole portfolio is checked once a year.

- More volatile elements (small-caps, spread bets) are probably checked once a month, though I might move up to once a week when markets are stretched or lively.

The fourth good trait is patience.

- This is another one that comes with a long-term orientation.

It’s important to focus on the compounding of steady returns, rather than to foster a “get rich quick” approach.

- This allows you to take advantage of “market dislocations caused by short-term players – crashes, bubbles, and cheap ignored and not-so-hot stocks”.

It means that you are prepared to wait for the best opportunities.

- And infrequent activity also keeps your transaction costs down.

Experience, talent and intelligence

Experience is obviously a plus, but only if the investor learns from it, and incorporates it into their methodology.

Frederik also believes in the importance of talent, by analogy with the fact that not everyone can be a doctor or sportsman or rocket scientist.

- I think the analogy is imperfect, in that quite a lot of people could be – for example – a GP.

- But Frederick’s comments probably only apply to investors who can beat the market over decades, which is a higher bar.

Of course, there can only ever be a few elite athletes, and it’s unlikely that most people would make it into the next edition of Frederik’s book.

- But the body of knowledge required to be a competent investor is much smaller than to be a competent doctor or rocket scientist.

- The physical attributes are non-existent in comparison to the sportsman, and the mental attributes much less complicated (perseverance, attention to detail, emotional control).

So I would say that talent plays a much smaller part.

- It’s more that investment competence is not covered by the mainstream media, and no career path to investment competence is offered to school-children.

Most great investors agree that above average intelligence is an advantage, but exceptional intelligence is not required.

- Many very intelligent people have failed in the markets (Newton is perhaps the most famous).

Potential downsides of very high intelligence include getting bogged down in the detail (I’ve definitely seen that), arrogance (see above) and an unwillingness to learn from mistakes.

- That has to be weighed against an advantage in speed of processing information and accumulating experience.

Buffett says that an IQ of 125 is enough – that actually only leaves about 5% to 6% of the population.

- I would argue that with today’s ETFs, a lot more people could get a satisfactory result on their own.

Conclusions

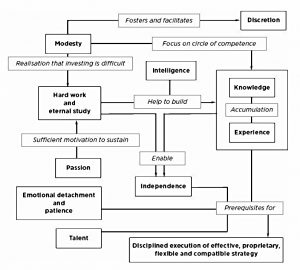

Frederik ends the chapter (and the book) with another summary diagram, this time showing the interplay between the various elements that we’ve covered today.

- I hope this one makes more sense to you than the earlier one.

So we’ve come to the end of the book.

It’s tailed off a bit for me.

- The early “surveying” chapters worked better than the later “conclusions” chapters.

- And the harder chapters worked better than the softer ones.

But it has by far the most content of any investing book I’ve read (witness the thirteen articles that’s it’s taken me to get through it).

I would recommend it to any serious investor.

- You can buy it by clicking on the image below.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0857194321]

Just don’t try to read it all in one sitting.

Until next time.

A very thoughtful piece Mike and I think we need more thought provoking articles like this one.

The thing that has often struck me when meeting successful investors has been their emotional detachment to such a degree that they often come over as quite cold, removed and lacking compassion.

I wonder sometimes if that is a price worth paying and it reminds me of ‘A Christmas Carol’ and Scrooge’s lack of compassion for his fellow man as his ‘Business’ motivates him- if people are suffering then “they had better do it (die) and decrease the surplus population”, but in his epiphany he finally realises that “the common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were all my business…”.

I also find it interesting when you remark that you have had little success in having your advice accepted by friends and relatives- I think this is when a true soft skill as emotional intelligence comes in handy.

I think that quite often, we investors can live in an investment ‘bubble’ and lose touch with what the common man or woman knows about savings and investment- which in truth is probably not much, and I have found that you need to use that emotional intelligence to better understand people and how they operate to effectively explain to them our ideas.

They would know little if anything about an OEIC or an ETF and we need to speak to them in their own language rather than our own.

Interesting stuff still!

Thanks for the detailed comment, Brian.

I agree with about a certain level of detachment being common amongst investors, but I don’t see it as a bad thing – it helps you to distinguish reality from spin. I’d rather be detached than like the rest.

Not do I see my inability to bring people with me on my investment journey as a failing on my part. I think there will only ever be a minority of people who look to the future.

I see it more as their loss in not having taking advantage of an accessible and free resource. And trust me, I have used their language. “You will be eating cat food when you are 70” has no effect on most people. They’d rather have an iPhone and a holiday.