Excess Returns 11 – Mistakes

Today’s post is another our series on the book Excess Returns, and looks at the mistakes that investors make in buying and selling stocks.

Contents

- Mistakes

- Picking tops and bottoms

- Selling a winner

- Hanging on to losers

- Overtrading

- Buy-and-forget

- Emotional trades

- Holding on to be right

- Waiting for a catalyst

- Trading based on tax

- Buying a laggard

- Targeting a precise entry price

- Selling after a takeover announcement

- Acting on what is well known

- This time is different.

- Too much attention to the economy

- Conclusions

Mistakes

In Chapter I of his book Excess Returns, Frederik Vanhaverbeke looks at mistakes people make in buying and selling stocks.

He comes up with fifteen of them.

- Most of these relate to well-known psychological biases.

Picking tops and bottoms

Many investors believe that they can buy at a price bottom and sell at a price top.

- This is down to overconfidence – even though investing is hard, it’s quite simple and therefore looks easy.

- Investors also believe in predictable price patterns.

Bottom fishers are likely to wait too long before buying, since they are reluctant to buy a stock after it has bounced.

- Similarly those who try to pick tops hang on too long and become reluctant to sell on the way down.

Instead, forget the top 10% and bottom 10% and try to trade the remaining 80%.

Selling a winner

Or to give it its longer name, selling a winner with a view to buying it back at a lower price.

- For this to work you need to time both a top and a subsequent (temporary) bottom.

If you miss the top, you are unlikely to buy back at a higher price.

- And if you pick the top, you need to take care not to wait too long for too low a bottom (bottom fishing again).

Hanging on to losers

I won’t waste too much time on this one.

- Peter Lynch calls this “Pulling out the flowers and watering the weeds”.

- We all know that we need instead to Cut Our Losses and Let Our Winners Run.

Anchoring to the purchase price is the chief reason here.

- Avoidance of regret (if a winner should become a loser, or a sold loser should recover) is another factor.

- Loss asymmetry is a third factor – losses hurt twice as much as wins feel good.

Overtrading

Many investors crave excitement, but successful investment is often boring.

Though transaction costs seem small per trade, they mount up.

- US and some other investors also have to think about taxes on short-term trades.

- But here in the UK, ISAs and SIPPs should mean that taxes are rarely a consideration.

Many studies have shown that those that trade the most have the lowest returns.

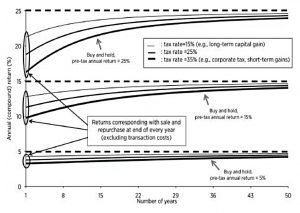

- Frederik has a chart of returns by average holding period (and also by US tax treatment).

- It shows annual returns of 5%, 15% and 25% before and after tax rates of 15% and 35%.

Top stock pickers usually hold for between two and five years, and will usually have something in their portfolio that they have owned for a decade.

You need to learn to Cut Out The Noise and trade only when your buying and selling criteria are met.

- This obviously matches best to Frederik’s preferred style of value investing, but it can be applied to most methods.

Buy-and-forget

I’m not too sure about this one, for two reasons:

- Where does buy-and-hold turn into buy-and-forget?

- There’s a famous (and perhaps mythical) study where a brokerage firm found that its best-performing client accounts belonged to those people who were dead (buy-and-forget taken to its logical extreme)

Frederik admits that his criticism only amounts to the fact that:

Buy-and forget is unlikely to beat the market over the long term.

That’s a first-world problem in my books.

- You won’t become a top investor via a buy-and-forget strategy, but you should do ok.

I wouldn’t recommend it for your entire portfolio, but there’s something to be said for focusing your attention on a more actively traded subset of your holdings whilst leaving the rest.

- This is a form of the “core and satellite” approach where half or more of your portfolio goes into safe passive funds.

Frederick points out that the top investors who do outperform using buy-and-hold tend to have concentrated portfolios and hold stocks for many years.

- He adds that they generally invest in exceptional companies, too.

- Fast growers and (very good) stalwarts are the best type of companies for a buy-and-hold strategy.

- Cyclicals and turnarounds need to be actively traded.

Emotional trades

This one is easier to back – I hope we can all agree that emotion has no place in investing.

- That’s easier said than done, of course, but the basic idea is to develop your own system (“borrowing” from your heroes) and then stick to it.

Frederick notes several types of emotional trades:

- Impatient trades

- before the “window of opportunity” closes

- or near the top of a bull market

- and also selling when you get bored with a stock

- Buying after good news / selling after bad news

- I’m not convinced that these are mistakes

- we know that profit warnings (the most common form of bad news) are rarely followed by recoveries

- and even good news often takes some time to filter through the market

- that’s not to say that the market doesn’t sometimes over-react in the hours after an announcement.

- Panic Selling

- in a crash, or near the end of a bear

- Trying to get even (recoup losses)

- Falling in love with a stock

- this leads to confirmation bias

- this is why I prefer not to meet the directors of a stock I am invested in

- hometown stocks and those that make products you love offer similar problems

- the key problem here is usually inaction (when you should really sell) rather than an emotional trade

Holding on to be right

Some people can’t bear to think that they were wrong to buy.

- Remember, Cut Your Losses

Waiting for a catalyst

This could be something like a takeover bid.

- Unfortunately, catalysts tend to be priced in the moment they become clear

Trading based on tax

This is less of an issue here in the UK, where SIPPs and ISAs (as well as VCT and EIS) allow us to avoid capital gains tax, but in the US this can be a problem.

- some UK investors will have taxable accounts, but with an annual capital gains allowance of £11.3K and annual stock returns of around 7% nominal, you need £150K in a taxable account to start worrying

- you can also buy back any shares you sold after 30 days

Buying a laggard

I’ve never heard of this before, but apparently some investors like to buy the Pepsi stock when the Coke stock is too expensive.

- As you can imagine, Pepsi will never catch up with Coke.

Targeting a precise entry price

Don’t miss out on a good stock because it stays marginally above your target entry price.

- Long-term potential is what counts.

Selling after a takeover announcement

Once again, I think this is a first-world problem.

- If the stock price has risen close enough to the bid value, you won’t do too badly by selling immediately and reinvesting the proceeds in a good prospect.

Of course, if a second bidder turns up, the price might go higher, but that’s a risk to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

- The flip side is that if the bid falls through, you might lose the premium over the price before the announcement.

Acting on what is well known

I think we’re back to Buy The Rumour, Sell The News here.

- What you need to do is look for things that might surprise the market, and back them if you think they are likely.

This time is different.

As we know, it never is.

Too much attention to the economy

I’m quite a fan of macroeconomics, (( I should point out that I like to review the historical data in particular – I’m not a fan of macro forecasts, or indeed much of a fan of forecasts of any type )) but it’s clear that there’s not much of a link between it and stock picking.

In general, super-investors don’t use macro very much.

- There is the obvious counter example of multi-asset traders of the Soros type.

Even the stockpickers expressed regret after failing to spot the macro-driven 2008 crash.

- Bubbles should not be ignored, even if you are no fan of macro.

A further caveat here is that over the decade since, central bank intervention (QE and low interest rate etc.) has had such an effect that macro has been impossible to ignore. (( Purists would argue that this is not macro, but it is to most DIY investors ))

There’s also the argument that sector-level economic analysis can be useful.

- For example, at the time of writing, UK high-street retailing faces many challenges, including the move to online shopping, and higher input costs from rising minimum wages and the post-Brexit weakening in Sterling.

Frederic’s final warning on this issue is to link it to overtrading (already mentioned above), since the macro weather changes frequently. (( I would argue that the forecast changes more frequently than the historic data ))

Conclusions

This is a comprehensive survey of mistakes from Frederic.

- But I think that:

- some of these are duplicates,

- some shouldn’t be lumped together, and

- some are not so serious as others.

So here’s my simplified list:

- Serious mistakes

- Hanging on to a loser

- Falling in love with a stock

- Holding on to be right

- This time is different

- Selling a winner

- Emotional trades (impatience, panic, trying to get even)

- Buying a laggard

- Targeting a precise entry price

- Picking tops and bottoms

- Overtrading

- Hanging on to a loser

- Not-so-serious mistakes

- Trading based on tax (not likely in the UK anyway)

- Acting on what is well known

- Not really mistakes

- Buy and forget

- Using macroeconomics

- Buying after good news / selling after bad news

- Selling after a takeover announcement

There are definitely only two more chapters (and two more articles) to go in this book.

- It’s proving to be the most dense book we’ve ever worked through.

I’ll be back in a few weeks with Risk.

Until next time.

Mike, thanks for a well composed summary.