Invest in the Best 1 – Philosophy and Growth

Today’s post is our first visit to a new book – Invest In The Best by Keith Ashworth-Lord.

Contents

Keith Ashworth-Lord

Keith Ashworth-Lord runs the UK’s Buffettology unit trust.

- He’s an Astrophysics graduate with a Masters in Management from Imperial.

He started buying shares aged 21, in the 1980s privatisation boom.

- He’s worked in the capital markets for 30 years and used to be Head of Research at Henry Cooke Lumsden.

I heard Keith speak at the Mello event in November 2018, and I knocked up a stock screen based on what he said.

Keith is from Rochdale – my home town – where his parents went bust running a corner shop.

- He’s a few years older than me, and unlike me, he still lives there.

- Even less like me, he runs a £1 bn fund from there (well, Manchester).

I’m somewhat sceptical that Buffett’s methods can be applied today in the UK, but Keith’s recent track record would appear to prove me wrong.

The Buffettology fund

The full name of the fund is the CFP Sanford DeLand UK Buffettology fund.

- Keith licences the “Buffettology” part of the title from Mary Buffett, who wrote a book of the same name.

- The other part of the name comes from two towns in Florida, where Keith has a second home.

Of course, Buffett’s style has changed at least twice over the years – deep value to GARP to private equity.

- This fund uses the mid-period GARP style, though Keith would not describe it that way.

It’s a fairly concentrated fund, with around 30 positions, which many people would see as a good thing.

- And it has low turnover, typically of 8% pa or less.

Since its launch in March 2011, the fund has regularly been at the top of the fund charts.

- It claims to be a general UK market fund but often has a mid- to small-cap bias.

Philosophy

The first part of the book explains how Keith came by his investment philosophy:

I execute a robust investment methodology that concentrates wholly on buying superior businesses at prices that make business sense.

My investment credo is that an excellent business bought at an excellent price invariably makes an excellent investment over time.

At Henry Cooke Lumsden, he saw the downside of the move from professional ownership structures (partnerships) to “professional managers”:

I had seen a franchise that took 125 years to build brought down in less than 125 weeks.

I learned that when investing in a business, it is a good idea to check out the equity ownership of the people running it and how much they are drawing in salaries.

If they have a large amount of personal wealth tied up in the business

and behave frugally, it is more likely that they will act like owners to preserve their wealth (and yours with it).

He also developed an aversion to mergers and acquisitions:

I had learned to be very wary of acquisition-led growth and the opportunities it provides for accounting smoke and mirrors.

In particular, he worked on a mini-conglomerate called Thomas Robinson:

Robinson became a serial rights issuer, returning to the market again and again for additional funds. Despite the marvellous profit record, no cash ever seemed to come out.

Robinson was using fair value adjustments to write down acquired stocks and debtors, thus booking greater profits when the stock was sold or the receivables collected.

Similarly, by writing down fixed assets, the depreciation charge taken against profits was reduced. In an instant I had learned the distinction between profits and cash.

Acquisitions provide a wonderful opportunity for creative accounting and

investors should view them warily. As long as you remember Cash is King, you won’t go far wrong.

Keith also lived through the dot-com boom of the 1990s.

You just know something is wrong when investment bankers start devising new

ways to value enterprises other than by their ability to generate cash for their owners.You move from earnings after tax, to operating profit, to EBITDA to revenue multiples and worse.

And the bust:

The darkest hour is just before the dawn. The point where nearly everyone is pessimistic and can see no positive news whatsoever. As the last bull turns to bear, the market inevitably turns up.

Real investment

Real investment had to be about taking a part ownership interest in a real business. The starting point is to identify particular types of company as investment candidates, i.e. those with the most predictable business models, then to value them.

Keith teamed up with Jeremy Utton, the founder of Analyst magazine, and over the next 11 years together they turned it into a Buffett and Munger fanzine.

They were both fans of Mary Buffett’s book Buffetology:

It showed us the overriding importance of concentrating on the economics of a business and discarding those companies that do not stack up against a set of predetermined criteria.

They went from focusing on cheap stocks to outstanding companies, from EPS growth rates to ROCE, and away from watching market price movements.

Keith credits this move to “Business Perspective Investing” with keeping him out of the dot com boom.

- I made money out of dot com, so I’m glad it didn’t keep me out.

Keith and Jerry started to attend the Berkshire Hathaway and made friends with the Buffettologists.

- In 1999 they held a Buffetology conference in London.

But the fund didn’t launch for another 12 years.

Business Perspective Investing

Business Perspective Investing is all about investing for the long-term. There is no philosophical distinction between part ownership (buying shares in a company) and outright ownership (buying the business in its entirety).

The craft of investment is to forecast the yield on an asset over the life, or holding period, of the asset.

There are a relatively small number of truly outstanding companies and more often than not, their shares can’t be bought at attractive prices. The price you pay determines the return you get.

Only an excellent business bought at an excellent price makes an excellent investment.

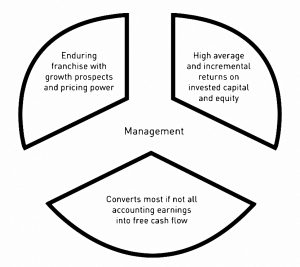

Keith has a list of attributes that make up a quality business:

- Easily comprehensible business model.

- Transparent financial statements.

- Enduring franchise with pricing power from superior competitive advantage.

- Consistent operational performance with relatively predictable earnings.

- High returns on equity capital employed.

- A high proportion of accounting earnings converted into free cash flow.

- Strong balance sheet without unduly high financial leverage.

- Management acts with the owner’s eye and is focused on delivering shareholder value.

- Growth from organic initiatives rather than acquisitions.

Like Buffett, Keith won’t invest in a business that he doesn’t understand – those outside his “circle of competence”.

I prefer to keep my circle of competence a foot wide and a mile deep.

You are unlikely to see me going near oil exploration companies, miners, banks or blue-sky pharmaceutical and biotechnology businesses.

I look for a business where I think I can understand the product, the competition and what might possibly go wrong over time.

Five forces

Competition continually works to drive down returns towards the cost of capital thus eliminating the potential for profit.

Keith uses Porter’s Five Forces framework and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) to analyse a company’s competitive position.

- Porter’s book (and SWOT) was used on my MBA almost 30 years ago, (( It’s still on my bookshelf )) and I’m surprised that things haven’t moved on since then.

The five forces are:

- The threat of new entrants.

- The Intensity of rivalry among existing competitors.

- Pressure from substitute products.

- Bargaining power (diversity) of customers.

- Bargaining power (diversity) of suppliers.

Keith prefers to invest in firms with superior management, but:

If you have big enough barriers around the franchise, you don’t need the ultimate management team to run it.

Once Keith finds a firm he likes, the next step is valuation:

I try to decide what I think the business will earn over the next five, ten or more years. I attempt to evaluate what the future streams of income and cash flow might be.

Growth

Not all growth is good.

Investors like companies to be growing because they believe that growth in

revenues, profits and earnings is what drives share prices.[But] companies can grow yet still destroy owner value. Focusing on growth alone neglects the equally important concepts of profitability of capital and free cash flow.

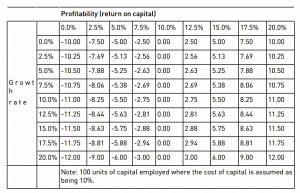

The creation of value in a business is the product of growth in earnings multiplied by profitability (defined as the return on capital), less the cost of that capital.

change in value = units of capital × growth rate × (return on capital - the cost of capital)

Until the return on capital equals its cost, growth actually destroys value. Indeed the higher the rate of growth, the more value is destroyed.

Beyond the hurdle rate of a 10% return, value is increasingly created with higher rates of growth and profitability.

More incremental value is created for a given increase in profitability rather than in the growth rate.

Keith doesn’t like companies that are over-focused on growth, or on short-term profitability – you need a balance.

Earnings

Share price = earnings * PE

GARP investing looks for growing earnings on an appropriate PE. Keith notes that:

There is no mention of returns on invested capital.

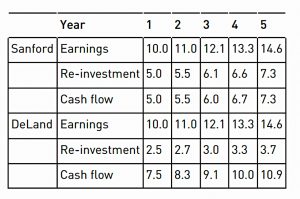

He illustrates with two hypothetical businesses – Sanford and DeLand.

- Both have the same earnings and growth rate, but they shouldn’t have the same PE.

- That’s because Sanford has to invest twice as much capital as DeLand to achieve that growth rate.

The cash performance (earnings less necessary new capital investment) of DeLand leaves Sanford standing over time.

So capital intensive companies are less attractive.

Cash flow only really becomes valuable once it becomes distributable. Managers of companies with slower intrinsic growth can boost their apparent returns by throwing more capital at the business.

This throwing of more capital at the business is often done by acquisitions. Worse still, if that capital is earning less than its opportunity cost, any growth produced actually destroys owner value.

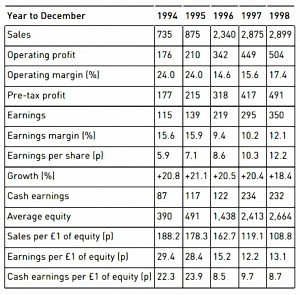

Keith illustrates these points using Rentokil:

Clive Thompson (Rentokil’s CEO) had earned himself the sobriquet `Mr. 20%’. This had been Rentokil’s annual earnings growth rate over the previous 14 years [before the acquisition of the larger BET].

Although the enlarged group’s overall earnings per share continued to rise by around 20% immediately after acquisition, the price in terms of dilution for Rentokil shareholders was massive.

Earnings per £1 of equity fell from 28.4% in 1995 to 12.2% in 1997.

- Cash earnings per £1 of average equity fell even more sharply from 23.9p in 1995 to 9.7p in 1997.

Accounting earnings growth continued for a time simply because a lot of cheap, tax-efficient debt was used to pay for the acquisition.

- Although the returns were above the cost of debt, the original Rentokil businesses had to divert their surplus cash flows to servicing and repaying the BET debt.

Organic growth

Keith has a checklist of how a firm can achieve organic growth, in order of increasing risk:

- Produce and sell more units of the same product or service.

- Sell the same products and services at higher prices.

- Sell to new customers who have not bought in the past.

- Develop and sell new products and services.

Conclusions

Although I’m far from a Buffett fan-boy – I greatly respect his achievements but find them hard to emulate in today’s UK market – I’ve enjoyed the first part of this book much more than I expected.

- Keith makes some very convincing and straightforward points in a relatively simple fashion.

I’m looking forward to the next part, which is about Profitability, Cash and Predictability.

We’re about a third of the way through the book already, so I only expect to write another couple of articles, plus a summary.

- And then I’ll probably have a go at improving the stock screener that I developed last year.

Until next time.