Own the World 3 – Surplus and Accounts

Today’s post is our third visit to How to Own the World, by Andrew Craig. Today we’re going to look at creating a surplus and at the available types of investment account.

Contents

Surplus

Live on less than you earn and invest the rest.

This is the most basic rule of personal finance.

- Obviously, if you have debts, the first use for your excess cash will be to clear them.

For more information, take a look at:

Andrew recommends saving at least 10% of your income, but I would suggest 15% to 20%, as I expect lower returns in the future.

- People who can’t do this are unlikely to end up rich, or even comfortable in their retirement.

See Do The Math for more detail.

Andrew recommends reframing the saving problem as a spending problem:

Work out how you can best spend 90% of your income each month, rather than how you can save 10% of it.

His second tip is more radical:

If you cannot save money given your current living arrangements, then change them.

Rent somewhere 10% or 20% cheaper (or downsize if you own) and invest the difference.

Andrew also recommends youneedabudget.com though many people should be able to manage with a simple spreadsheet.

Property

The decisions you make about property in particular will have a huge impact on your wealth over your lifetime.

Because property is such an important asset class to most people in the UK, Andrew discusses it in some depth.

Andrew thinks that the obesssion with home ownership in the US and UK was behind the financial crisis.

Many people [fail] to understand how to value property over time, as against the other main assets you might put money into such as shares, bonds and commodities.

We have lived through at least twenty years of most people believing that “you can’t go wrong with bricks and mortar” or that “rent is throwing money away by paying someone else’s mortgage”.

Like all assets, sometimes property is good value and worthy of investment, and at other times it is dangerously expensive.

There is more detail on this in our article on Property as an asset class.

- Property is illiquid and expensive to trade, and comes with costs of ownership.

- Though the paradox of today’s high prices is that these costs are much lower in percentage terms than they used to be.

Anchoring

There is nothing like a rampant bull market in an asset class to make everyone feel like a genius.

If something has been true in your personal experience (in this case, rising property prices) you will tends to assume that it is normal and possibly always true.

- In reality, sometimes property is a good investment, and sometimes it is not.

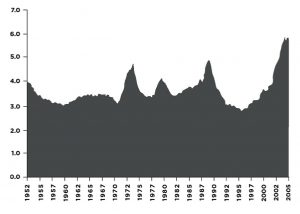

UK property basically did not appreciate in value at all from 1900 to 1960.

Inflation

Andrew reminds us that the pound has fallen in value by 90% since 1971 (due to inflation).

This is why prices from the early 1970s seem so incredibly “cheap”.

So while house prices in London have increased by 50 times since then, in real terms they have “only” increased by five times.

- And if a person selling this London house wants to buy another one (which has also increased by five times in real terms) then they are no better off at all.

Of course, if they want to move to rural Scotland, that’s another matter entirely.

- Prices there may “only” have increased by say 25 times, and our seller can now buy twice as much house in that area.

The house owner is also better off in terms of things link meals out or airplane flights.

Andrew also considers exchange rates by looking at translating a London house into a New York house.

- Andrew thinks that dollar values in particular are important, since most commodities are priced in dollars.

I think that negative FX shocks tend to result in a short term boost to inflation via imports (the post-Brexit-vote crash in Sterling is a good example).

- But FX movements tend to net out over the course of an investing career.

- And I think that the deflationary impact of improving technology and productivity tends to outweigh inflation – most “things” are cheaper in real terms than when I was a child.

The bottom line is that purchasing power is what counts, not nominal pounds.

Valuing property

To value property, Andrew recommends rental yield and the ratio of property prices to salaries.

- Of the two, I prefer yield since it can be used to measure the attractiveness of property against other asset classes.

Further, interest rates affect property affordability.

- The current low interest rates support higher property to salary ratios than the high interest rates of my youth.

Low rental yields (and poorer prospects for capital appreciation) are the reason I’m not a great fan of Buy-To-Let.

- I live in London, where gross rental yields are just above 3%.

That’s below my safe withdrawal rate, even before deducting running costs, voids and agency fees.

- Andrew reckons these reduce the yield by more than 0.6%, giving me a likely net yield of 2.4% – not enough for all the hassle.

If you have borrowed to finance the purchase, you need to subtract your interest payments.

- With a net yield of less than 3%, most will be taken up by interest (assuming say a 70% mortgage).

You also need to add in likely capital appreciation (negative in London at the moment) and subtract inflation in order to get a real rate of return.

- And then you need to look at your tax situation to come up with an after-tax real rate of return.

That’s the only number that matters.

- Compare that number with the FTSE-100 yield (currently around 4%) and its average capital return (around 5% pa) you can see why property is not the no-brainer that many people think it is.

House prices and salaries

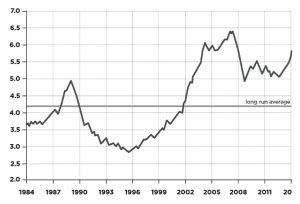

Andrew sees this as a key measure of affordability, but I think you have to take interest rates into account.

- If you can borrow enough money, houses are cheaper (in terms of repayments) today than they were 25 years ago (when interest rates were much higher).

Whether buying a house at six times your salary is a good investment is another question entirely.

- The UK historical average is between three and four times.

Andrew points out that in 2006 houses looked expensive relative to salaries, and might be expected to show poor returns.

House prices did crash in 2008, but then so did everything else, so it probably wasn’t entirely down to the salary ratio.

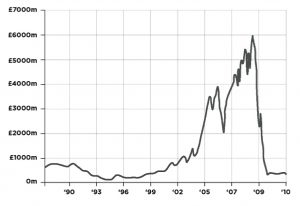

Lending for house purchases also fell.

- With lower demand, you can expect prices to fall (other things being equal).

Andrew also discusses what I think is the key point about property:

It is the one asset that a private individual can borrow meaningful sums of money to buy.

This gearing amplifies gains (and sometimes losses) and explains why so many people think that the returns from property are high.

- Stock market returns would be even higher if you juiced them with 95% gearing.

Andrew also mentions the endowment effect.

- People over-rate the things they already own.

- They can’t accept that “their precious” has fallen in price, and will wait for the “right” offer.

This makes property owner more likely to reject low-ball offers for their property.

- Which acts as a brake on nominal price falls.

- Of course adverse personal circumstances (eg. job losses) can force sales and trigger a real crash.

The same thing happens with shares, of course.

- See Cut Your Losses for more details.

Overall, he concludes that UK property is already expensive, with likely headwinds from rising interest rates and inflation, and low bank lending.

- Andrew is writing before the changes to the tax regime designed to discourage BTL.

Financial deregulation

Andrew blames deregulation (easy borrowing, interest-only mortgages) for the escalation in UK and US property prices, and there’s some truth to this.

- Incentivised lending against an asset whose price is fuelled by that lending is always going to be tricky.

It’s also the case that the separation of lender and owner of the debt (securitisation) was a big factor in the 2008 crisis.

He mentions the French affordability criteria for borrowing (one-third of gross income as mortgage repayments).

- Since he wrote the book, similar measures have been introduced in the UK, but of course they are distorted by low interest rates.

Accounts

Andrew begins by looking at current accounts, which he says “leave a great deal to be desired.”

- We all have our own bugbears (mine is being referred to the fraud department the first time I try to pay anyone), but in one respect our accounts are pretty good.

Despite low or no interest (or high interest capped on deposits of a few thousand pounds), our current accounts are mostly free to use (for some of us).

- Those who run an overdraft subsidise those who don’t, just as those who run credit card balances subsidise those of us who don’t.

And the new online challenger banks will make things even better.

- More on that in a future post.

Note that I’m not advising using your high street bank for anything other than a current account.

- The cross-selling of additional products is usually very profitable for them and a very poor deal for you.

Pensions

As most people know, there are three types of pension (Andrew divides them into two):

- the state pension

- a defined-benefits (DB) company pension (on their way out, except in the public sector)

- a defined contributions (DC) pension, where you and / or your employer can make contributions

- actually, contributions from both are required nowadays unless you opt out of your workplace pension)

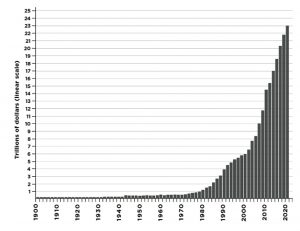

Andrew thinks that state pension schemes around the world are all bankrupt.

- He thinks that governments should have saved while their demographics were favourable.

- Instead, they borrowed more – here’s a chart of the US national debt.

He thinks that governments will continue to “print” money, inflating away the value of future pensions

Andrew has a point about national debts, but he is wrong about state pensions.

The unfavourable demographics (pensioners living longer, and fewer workers to support them) can be countered by gradually raising the state retirement age.

- The UK state pension will not increase significantly as a share of GDP over the next 35 years.

- See the State Pension Age Review for more details.

People can still expect to get a state pension, just at a later age (eventually, after the age of 70).

- The Government target is that the state pension should cost less than 8% of GDP and support people through the last third of their adult life.

The more important point about the UK state pension is that it is inadequate – only £8K pa.

- Despite acres of negative press for the “triple lock”, the UK has the smallest state pension (as a share of average wage) of any rich (OECD) country in the world.

So you have to make private provision for your pension.

- This is also Andrew’s ultimate point – the state pension won’t be big enough on its own.

All Andrew has to say about DB pensions is that if you have one, keep hold of it.

Within DC pensions, he prefers the flexibility of SIPPs to workplace pensions.

- Though you should of course make the minimum contributions to a workplace pension to guarantee your employer match.

Pensions vs ISAs

Andrew prefers ISAs to SIPPs, because you can access your money at any time.

- You can’t access your SIPP until age 55, and that threshold is likely to increase.

But of course, so long as you expect to be alive past 55, you can use some combination of ISAs and SIPPs, and run down your ISAs if you manage to be able to retire before 55.

Andrew expects governments to raid pension pots (but strangely not ISAs) as part of his “bankrupt governments” scenario.

- He thinks pensions are a more likely target because they hold more money.

There’s no doubt that UK governments have a bad record of tinkering with pension rules, but they are yet to steal private pension money.

- Indeed, the thrust of the past few years has been to incentivise more peopld to save in workplace pensions (auto-enrolment).

Andrew also plays down the tax relief issue.

- Pensions are EET (taxed at the end).

- ISAs are TEE (taxed at the beginning).

EET is better because:

- You are likely to have a lower tax rate in retirement.

- Using the tax-free lump sum and your personal allowance means your likely tax rate could be as low as 11%.

- The bigger initial investment will compound up into a larger sum.

The advantage is greater for 40% taxpayers.

Added to this, the annual ISA contribution limit has historically been low, and even the current £20K allowance is only half of the £40K annual pension contribution allowance.

- See ISAs vs SIPPs for more detail.

Pensions are also in effect exempt from IHT.

- Andrew plays down the importance of this, pointing out that you can just give away your assets seven years before you die.

Andrew makes an exception from the “ISAs better than pensions” rule for employer matching, and for people who can save more than the ISA limit (£20K pa today).

- Although it should be noted that he recommends high earners use a taxable account and the annual CGT allowance and / or spread betting before locking money away in a pension.

ISAs

The most important point that Andrew makes about ISAs is that you should avoid Cash ISAs.

- Cash is a poor long-term investment.

He does not recommend a particular ISA in the book, referring us instead to the website.

- On the website, all I could find were recommendations to read Andrew’s book, take one of his courses, or become a private client.

He does remind us in the book not to use the ISAs from the high street banks.

- They will tend to be expensive, and to have a poor range of investments.

Spread-betting accounts

Andrew reccomends spread betting, for those who “are prepared to put in a decent amount of work.”

The two main features of spread betting are:

- leverage – you can hold positions much larger than the cash in your account

- this is good if you win and bad if you lose

- you can go short – bet on things going down in price.

Most people (90%?) lose money spread betting, so make sure you do some reading first.

- We have a series of articles on spread betting that you can find here.

Conclusions

Today we’ve looked at running a surplus, and at the types of account that you need.

- Spending less than you earn – and investing the difference is the only way to become wealthy.

- You should save at least 10% of your income, and ideally 15% to 20%.

- Property is a key asset class for most people in the UK.

- But it is not always a good investment.

- You need to learn how to value it, via rental yield and affordability.

- Buy to Let is no longer the great investment that it once was.

- People exaggerate the returns from property because they use leverage.

- The endowment effect often slows nominal property price falls.

- Purchasing power is a key concept, and more important than nominal valuations.

- Inflation and FX both impact purchasing power.

- Andrew thinks that the UK state pension system is bust.

- It isn’t, but the state pension is too low to live on, so you need to make private provision as well.

- You need a pension (SIPP) and an ISA.

- Andrew prefers the easy access of ISAs but for most people (particularly higher rate taxpayers) the returns from SIPPs will be higher.

- Your ISA must not be a cash ISA, or from your high street bank.

- You need a spread bet account.

- They offer leverage, selling short, and tax-free profits.

- Most people lose money, so do some reading first.

That’s it for today.

- I’ll be back in a few weeks with the next chapter, which is about the types of investment that you need.

Until next time.