Have people stopped saving?

Today’s post is a summary of what I said and didn’t say on one of the panels at last week’s Show Me The Money blogger awards, better known as the SHOMOs. The question we were discussing was “Have people stopped saving?”

Contents

- The SHOMOs

- The bottom line

- What is saving?

- What are we saving for?

- How much do we need to save?

- How much should we save each year?

- What does this mean?

- Debt

- How much are we saving?

- Why aren’t we saving more?

- Where to save?

- Did we ever save enough?

- Will FinTech save us?

- Will auto-enrolment save us?

- What should be done?

The SHOMOs

The UK Money Bloggers awards – better known as the SHOMOs (which stands for Show Me The Money) – were held in London on Saturday.

For the second year running, I was nominated for best investment or retirement blog, but for the first time, I actually won the award.

- Which is fantastic, so I want to thank Andy and the team for that.

I was also on a panel discussion in the morning, with the topic of “Have people stopped saving?”

It was a tough crowd (surprisingly, lots of money bloggers are not really into savings and investment) and I didn’t get all of my points across.

- But if I had been giving a speech rather than being part of a panel, this is what I would have said.

The bottom line

I’m going to argue that although we clearly aren’t saving enough today, we never have been, so it isn’t fair to say that we’ve stopped.

- I’ll also say that FinTech and auto-enrolment – as currently configured – won’t save us.

- And that eventually some element of compulsion will need to be introduced.

What is saving?

Before we can say whether people have stopped saving, we need to answer four questions:

- What is saving?

- What are we saving for?

- How much do we need to save – what does “good” look like?

- Were we ever saving enough – how do today’s saving levels compare with the past?

Let’s start with the first question – what is saving?

At its most basic, we are saving in order to defer present consumption to a later date.

- This is usually because we have a surplus today, and expect a deficit at some point in the future.

- This will usually be at retirement, but could be earlier if we are planning a change of lifestyle.

In order for our savings to support future consumption effectively, they need to act as a store of value.

- Put another way, we need to be able to preserve our purchasing power by making sure our savings keep up with in inflation.

- We’ll come back to this later when we look at where to put our savings.

What are we saving for?

On to the second question – what are we saving for?

- Ultimately, we’re saving for retirement, or financial independence as many people prefer to reframe it these days.

Along the way, we’ll put together an emergency fund (or rainy day fund), and most of us will also save up for a house (or rather, pay down a mortgage).

- A minority of people will have other intermediate goals, like paying for future school fees or a child’s wedding.

How much do we need to save?

We’ve looked at this question before, but the basic maths remains the same.

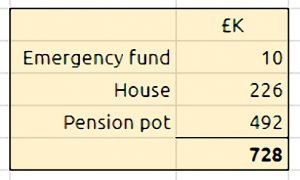

For the emergency fund, the standard advice is to aim for six months of living expenses.

- Depending on where you look, the average wage in the UK is between £26K and £28K pa.

- After tax, that will be closer to £21K.

So your emergency fund needs to be around £10K or so.

- Of course, your mileage may vary – you could have more or less than this.

For the house, the key phrase is “location, location, location”.

- The average UK house price is £226K, but depending on where you want to live, it could be significantly less than that or much more. (( For example, the street I grew up on, versus the street I live on ))

To keep things simple, we’ll use the average figure of £226K.

- Trust me, it won’t make the total any more palatable.

The more elaborate calculation is how much you need for retirement.

Let’s assume for now that our saver on the average wage would like to have the same £21K pa after tax that they have now.

- Retired people don’t pay NI, so the gross income needed is only around £24K.

Of that, £8K could be provided via the state pension, at some age beyond 66 (and possibly beyond 70 by the time people just joining the workforce are ready to leave).

- So we need to find a supplementary income of £16K pa.

There are two ways to convert this income requirement into a pot size:

- annuity rates, or

- safe withdrawal rates (in income drawdown)

Annuity rates for a £100K pot are:

- at age 65, £5.2K pa with no indexation or £3.2K pa with RPI indexation

- at age 70, £5.8K pa (no RPI) or £3.8K pa (with RPI)

These rates translate to pension pot sizes of between £290K and £460K.

But annuities are poor value, and you need to live a long time to get your money back.

- Income drawdown is much better.

The classic safe withdrawal rate (SWR) from 25 years ago in the US is 4% pa.

- Under present conditions, 3% pa would be much safer, but we’ll go with 3.25% to be generous.

That means you need a pot of £492K to produce a safe income of £16K.

So the total amount we need to save (on average) is 10 + 226 + 492 = £728K.

- Told you it was a scary number.

How much should we save each year?

That target looks a lot (and it is), but we have a long time to save it, and we can expect some contribution from the growth in our investments.

- Optimistically, some people will be saving from their late twenties, for perhaps 40 years.

- Pessimistically, some people will start saving at 40 or 45, and might only have 25 years to build up a pot.

As for growth rates, historically, 4% or 5% (after inflation) might have been a reasonable assumption for the UK.

- But under current economic conditions, I’d prefer to use 2% pa real.

So let’s run the numbers for both growth rates.

In order of increasing difficulty:

- over 40 years at 4% growth, you need to save an average of £7.3K per year

- over 40 years at 2%, it’s £11.7K pa

- over 25 years at 4% growth, you need to save £16.4K pa

- and over 25 years at 2%, you need to save £21.7K pa

What does this mean?

Clearly these higher annual figures are impossible for someone on an average wage, but people on higher incomes might well be satisfied with £24K pa in retirement.

- People on average incomes and less could use a simple percentage target.

- Something in the region of 15% to 20% of gross income would be about right.

Those who can’t save £7K pa have two options:

- increase their income

- reduce their spending, both in the present and in retirement

Frugality goes hand in hand with saving, and if you can reduce your living expenses significantly (or increase your income) then the problem becomes much easier.

- Rather than putting a few pounds away when you can, You Need a Plan for life, which documents your needs and how you will meet them.

It’s been a long preamble so far, and I promise that I didn’t go into such detail on the panel.

- But the key point is that to hit significant life goals, people need to save a lot of money each year.

And if they can’t save that much or close to it, there’s not a great deal of point in saving at all.

Debt

Before we look at how much we’re saving, we should briefly consider the role of debt.

- Consumer credit has never been easier to access, and stands at record levels.

At the same time, interest rates are at record lows, so people don’t yet feel the pain of this burden.

Before you can save for the future you need to clear your debts.

- Better still, don’t have any debts in the first place.

The only acceptable debt is a mortgage on a house.

- A house is – over the long-term – an appreciating asset.

Everything else (cars especially) is a wasting asset, and should only be bought with cash.

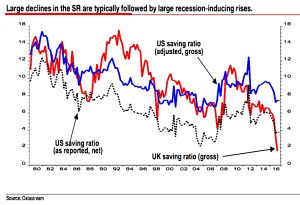

How much are we saving?

The short answer is not enough.

- A few weeks ago the UK savings rate hit rock bottom.

And a couple of weeks after that it was announced that contributions into cash ISAs had fallen.

- With the recent growth in stocks, stocks ISAs had overtaken cash ISAs.

But that’s a red herring.

- The money that used to go into cash ISAs has been diverted into ordinary current accounts.

- These pay more interest, and with the recent introduction of the savings allowance, the first £1K of interest is sheltered from tax.

- At current interest rates, that more than takes care of the emergency fund.

The bigger problem is that pension pots are woefully inadequate.

- Depending on who you ask, the average pot is between £35K and £50K.

- Which is a long way short of the £728K that the average person needs.

Why aren’t we saving more?

There are a lot of possible reasons, but three stand out:

- People don’t know how much they need to save, or the consequences of not saving.

- Or they do know, but they don’t care.

- Or they do know, but they don’t think that they can do anything about it.

It’s true that incomes vary widely, and many people will find it hard to save.

- But it’s also true that if you can’t save 15% to 20% of your income, you will never have a secure financial future.

People are short-term thinkers, and investing is a long-term process.

- It’s hard to get people to think about 20 or 30 years into the future.

This is not to ignore the impact of low interest rates, or the perceived complexity of investment.

Where to save?

This is less important than getting people to save in the first place, but let’s look on the bright side:

- High interest current accounts are fine at the moment for an emergency fund.

The best home for the rest of your money is a pension.

- Workplace pensions benefit from employer contributions.

- And all pensions benefit from income tax relief up front.

And remember to put your pension into a globally-diversified multi-asset portfolio (if you don’t know what this is, find out here).

- Cash is no good for long-term savings – it isn’t a store of value.

Young people are uncomfortable with locking their money away for decades, and they will sometimes try to justify this by arguing that the tax needs to be paid sometime.

- But growing gross contributions tax free will outpace growing net contributions.

And when you draw the pension, you can take advantage of the 25% tax-free allowance and your personal allowance.

- So instead of 20% (or 40%) up-front, you pay something closer to 11% on a larger pot.

I can see the attraction of the LISA to a first-time buyer, but otherwise, fill your pension before your ISA.

- The only wrinkle in that plan is if you want to retire before 55.

- You’ll need enough in your ISA to get you from your retirement age to 55.

Did we ever save enough?

Sort of, but not really.

Pensions are a relatively new idea, and were originally granted at subsistence levels to people who were already beyond the average life expectancy.

The last couple of decades have seen a lot of people retire on generous defined benefit pensions which create the false impression that lots of people have been saving enough.

- But it was the employers who did the saving.

- And if they had got their calculations right in the first place, they would have saved a lot less.

When economic conditions changed, and low interest rates pushed DB pension schemes into deficit, employers were quick to replace them with DC schemes.

- That generation probably won’t end up saving enough, and things are likely to get worse over time.

Will FinTech save us?

Not really.

- Fintech – as it currently stands – is just a sexy front end on the traditional model of shoving investors into funds, be they passive or active.

And it’s not even cheaper than do-it yourself.

It’s quite likely that more millennials will engage with FinTech, and save more than nothing.

- But will they save £7K to £10K a year?

The auto-save programs that round up transactions are worth a mention:

- at 50p for the average round-up, £7.3K a year needs 40 transactions per day.

Will auto-enrolment save us?

Not as it’s currently configured.

- The new system has got a lot more people saving, but the amounts involved are tiny.

It’s 2% pa at the moment, rising to 9% pa in 2019.

- This is way short of the 15% to 20% pa that’s needed.

And worse than that, it’s voluntary – you can opt-out at any time.

What should be done?

I’ve been saving for more than 30 years, and the UK has the most benign savings and tax system that it’s ever had during that time.

- You can put £40K into a pension and £20K into an ISA, every year.

That’s more than enough for anyone (assuming you can find the money).

- But yet people don’t save.

If incentives (tax breaks) aren’t working, then we should consider replacing the carrot with the stick.

- We should move to compulsory auto-enrolment contributions, at a minimum of 15%, as in Australia.

- And we should find a way to include the self-employed in the system, which might be tricky.

Until next time.