Predictably Irrational 4 – Dishonesty, Cash and Influence

Today’s post is our fourth visit to the book Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely.

Character

Chapter 10 is about dishonesty, and what we can do about it.

Dan seems particularly interested in why white-collar crimes – which inflict more financial damage than things like robberies – are judged less severely?

- I should declare a bias here – I would much rather see robbers and burglars punished than accounting and insurance frauds.

I want to be free to live my life without interference, and crimes directly against my person or my property outweigh all others.

Dan has a theory that there are two kinds of dishonesty.

- The behaviour exhibited by criminals,

- And the dishonesty perpetrated by those of us who think we are honest

- This is the kind of “victimless” stretching of boundaries that we might all attempt if we thought we wouldn’t be punished.

This theory fits pretty well with my own feelings on punishment.

- To test it, Dan tried to make some “honest” people cheat.

Subjects answered multiple-choice general knowledge questions and were paid ten cents for each correct answer.

- They had to transfer their answers to a machine-readable page

- And for half of the subject, this sheet had the correct answers shaded grey (providing the temptation to cheat).

In one experiment they handed both answer sheets in, and in the second variation, they were allowed to shred their original answer page (destroying the evidence of cheating).

- In a third variation, they shredded both sheets, and merely took the amount of money they felt that they were owed from a jar full of coins (so no possibility of being caught).

The controls scored 65% and the second group bumped that up to 72%.

- The third and fourth groups also scored 72%.

When given the opportunity, many honest people will cheat. The majority of people cheated, and that they cheated just a little bit.

The second, and more counterintuitive, result was [that] once tempted to cheat, the participants didn’t seem to be influenced by the risk of being caught. [And] even when we have no chance of getting caught, we still don’t become wildly dishonest.

We care about honesty and we want to be honest. The problem is that our internal honesty monitor is active only when we contemplate big transgressions, like grabbing an entire box of pens from the conference hall.

For the little transgressions, like taking a single pen or two pens, we don’t even consider how these actions would reflect on our honesty and so our superego stays asleep.

I agree with Dan that there is no explicit cost-benefit analysis preceding small acts of dishonesty.

- But I prefer the “reasonable man”/”red face” tests – would my behaviour be seen as acceptable by most people?

So at an investor conference, I might take home a pen (or even two if the person sitting next to me left theirs behind).

- I might have second helpings at lunch, once everyone else has been served.

But I wouldn’t scour the room for extra pens at the end of the event or tip plates of biscuits into my jacket pockets.

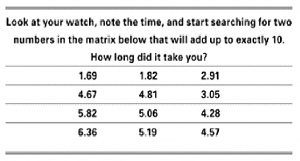

Dan’s second experiment was a maths test requiring subjects to find pairs of numbers within a matrix that added to ten.

- They had five minutes to solve as many problems as possible.

Some handed their answer paper in, others wrote their total on a second sheet (with the opportunity to cheat).

- They were then entered into a lottery for which the prize was $10 per correct answer.

Before the experiment, subjects were primed by either writing down 10 books they read in school, or writing down the 10 commandments.

With no cheating, the average score was 3.1

- With cheating, book recallers scored 4.1 (33% extra)

- The 10 commandments writers scored 3.0 – they didn’t cheat

The students who could remember only one or two Commandments were as affected by them as the students who remembered nearly all ten. It was not the Commandments themselves that encouraged honesty, but the mere contemplation of a moral benchmark of some kind.

Perhaps we could bring the Bible back into public life. Some people might object, on the grounds that the Bible implies an endorsement of a particular religion, or merely that it mixes religion in with the commercial and secular world.

But perhaps an oath of a different nature would work.

Dan considers professional oaths, and in particular those used by lawyers.

- Deregulation of the profession since the 1960s – to make it less “elitist” – has led to a drop in standards.

A preponderance of attorneys in California were sick of the decline in honor in their work and “profoundly pessimistic”.

Nearly 80 percent said that the bar “fails to adequately punish unethical attorneys.” Half said they wouldn’t become attorneys if they had to do it over again.

The same applies to doctors, and even petroleum geologists.

So Dan’s next experiment tests the effect of an oath.

It used the maths test again, with three groups:

- the controls handed in their answer sheet

- the cheaters simply stated how many puzzles they had solved

- the oathers could also cheat, but they had to sign a statement before the test: “I understand that this study falls under the MIT honor system.”

The controls scored 3 out of 20, and the cheaters 5.5

- The oathers stuck with three – again, no cheating.

Since MIT doesn’t even have an honour code, the impact of a moral reminder is pretty impressive.

It is clear that oaths and rules must be recalled at, or just before, the moment of temptation.

Dan worries that a lack of honesty will lead to a lack of trust, and he has a point, but I can’t say that trusting a stranger plays a big role in my life.

- Credit card companies, banks, property rights and fair courts are much more important, at least here in the UK.

He recommends that we avoid conflicts of interest (or as I would call them, skewed incentives) wherever possible, and I agree.

Cash

Chapter 12 looks at why dealing with cash makes us more honest.

Dan notes that most people would bring a pencil home from work, but they wouldn’t take money from the petty cash to buy one in a shop.

To test the effect of cash, Dan left cans of Coke and dollar bills in communal student fridges.

- Within 72 hours, all the Coke was gone, but none of the dollars had been touched.

Cheating is a lot easier when it’s a step removed from money. What permits us to cheat when cheating involves non-monetary objects, and what restrains us when we are dealing with money?

Dan’s second experiment repeated the maths test honesty setup from the previous chapter, but half of the subjects were paid in cash, and the others received tokens which they could exchange for cash with a second experimenter.

- The controls scored 3.5, the cheaters upped this to 6.2 and the token group upped this even more – to 9.4 (that is, more than twice the level of exaggeration).

There was also a massive increase within the token group of people who claimed to have answered all 20 questions correctly.

The tokens in our experiments were transformed into cash within a matter of seconds. What would the rate of dishonesty have been if the transfer from a nonmonetary token to cash took a few days, weeks, or months (as, for instance, in a stock option)?

Dan is clearly not a fan of stock options, but I’m not entirely clear how you cheat with them.

- They might lead to a sub-optimal focus on the short-term share price performance – but that’s not cheating.

Interestingly, other subjects failed to predict that the students given tokens would cheat more (whereas it seems entirely predictable to me).

Moving from words to deeds, a lot of people seem to exaggerate their insurance claims (industry estimates suggest a 10% inflation).

- “Wardrobing” (wearing clothes before returning them) costs the clothing industry around $16 bn pa.

And we all know people who have padded their expense reports.

Investigations into expense accounts turned up rationalizations. Buying a mug for five dollars for an attractive stranger was clearly out of bounds, but buying the same stranger an eight-dollar drink in a bar was very easy to justify.

When people give receipts to their administrative assistants to submit, they are then one additional step removed from the dishonest act, and hence more likely to slip in questionable receipts.

Businesspeople who live in New York are more likely to consider a gift for their kid as a business expense if they purchased it at the San Francisco airport than at the New York airport.

In view of the recent move away from cash, accelerated by contactless payments in the time of Covid, Dan has some sobering conclusions:

Electronic transactions make it easier for people to be dishonest -without ever questioning or fully acknowledging the immorality of their actions.

The dishonesty that we saw in our experiments was probably the lower boundary of human dishonesty: the level of dishonesty practiced by individuals who want to be ethical and who want to see themselves as ethical – the so-called good people.

“Bad people” – Dan uses Gordon Gekko as his example – would no doubt behave much worse. He quotes Upton Sinclair:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Adding:

It is even more difficult to get a man to understand something when he is dealing with non-monetary currencies.

Influence

In Chapter 13, Dan wanted to know whether people in rounds (in pubs) are influenced by the orders given before their turn.

- And whether that influence (if any) leads them to enjoy their beer more.

There were (free samples of) four beers to choose from in the experiment:

- Copperline Amber Ale: A medium-bodied red ale with a well- balanced hop and malt character and a traditional ale fruitiness.

- Franklin Street Lager: A Bohemian pilsner-style golden lager brewed with a soft maltiness and a crisp hoppy finish.

- India Pale Ale: A well-hopped robust ale originally brewed to withstand the long ocean journey from England around the Cape of Good Hope to India. It is dry-hopped with Cascade hops for a fragrant floral finish.

- Summer Wheat Ale: Bavarian-style ale, brewed with 50 per cent wheat as a light, spritzy, refreshing summer drink. It is gently hopped and has a unique aroma reminiscent of banana and clove from an authentic German yeast strain.

Half of the subjects (seated in groups) gave their choice out loud to a waiter.

- The other half wrote their orders on menus.

When ordering sequentially (publicly), [people] order more types of beer per table – in essence opting for variety.

If people choose beer that nobody has chosen just to convey uniqueness, they will probably end up with a beer that they don’t really want or like. Those who made their choices out loud, were not as happy with their selections as those who made their choices privately.

With one exception – the first person to choose out loud was unencumbered by the choices of others, and their satisfaction was not impaired.

In a second experiment with wine, Dan also looked at the impact of personality traits.

What we found was a correlation between the tendency to order alcoholic beverages that were different from what other people at the table had chosen and a personality trait called “need for uniqueness.”

That makes sense.

People are sometimes willing to sacrifice the pleasure they get from a particular consumption experience in order to project a certain image to others.

I think social media has demonstrated this in spades in the years since the book was written.

In other cultures – where the need for uniqueness is not considered a positive trait – people who ordered aloud in public would try to portray a sense of belonging to the group and express more conformity in their choices.

In Hong Kong, participants were more likely to select the same item as the people ordering before them.

Dan’s advice is to plan your order before the waiter arrives, and stick to it, no matter what anyone else orders.

- You could even announce your order to the table beforehand.

Of course, this assumes that we will be going back to restaurants after Covid.

Free lunches

Standard economics assumes that we are rational. And even if we make a wrong decision from time to time, we will quickly learn from our mistakes either on our own or with the help of “market forces.”

Clearly, as Dan has shown, we are far from rational.

- And we need economics which reflects that – behavioural economics to match with behavioural finance.

One of the main differences between standard and behavioral economics [is the] concept of “free lunches.” Economic theory asserts that there are no free lunches – if there were any, someone would have already found them and extracted all their value.

But in behavioural economists, context and emotion mean that people make mistakes.

Why not develop new strategies, tools, and methods to help us make better decisions and improve our overall well-being?

Which is the point of behavioural finance – to develop rules that will protect you against the biggest investing mistakes.

Dan uses the example of inadequate retirement savings.

- People are short-term thinkers – they procrastinate and prefer immediate benefits to those in the future.

My answer is mandatory retirements savings, but Dan prefers “save more tomorrow” from Richard Thaler (of Nudge fame).

When new employees join a company, they are asked to make about what percentage of their paycheck to invest in their company’s retirement plan. They are also asked what percentage of their future salary raises they would be willing to invest in the retirement plan.

It’s easier to sacrifice this hypothetical money, so contributions should be larger.

- In a test, savings rates gradually increased from 3.5% to 13.5% (over a few years).

Conclusions

Dan’s main lessons are:

- We are pawns in a game whose forces we largely fail to comprehend. We usually think of ourselves as sitting in the driver’s seat, but, alas, this perception has more to do with our desires than with reality.

- We are limited to the tools nature has given us, and the natural way in which we make decisions is limited by the quality and accuracy of these tools.

- Although irrationality is commonplace, it does not necessarily mean that we are helpless. We can try to be more vigilant, or use technology to overcome our inherent shortcomings.

- Policymakers could consider how to design their policies and products so as to provide free lunches.

That’s it – we’ve finished the book.

- It’s been fun to revisit after quite a few years away – I hope you got something out of it, too.

I’ll be back with a summary of the four articles in a few weeks.

- Until next time.

“So at an investor conference, I might take home a pen (or even two if the person sitting next to me left theirs behind).”

thought that was only me!!