The Upside of Irrationality 2 – Ownership, Not-Invented-Here and Revenge

Today’s post is our second visit to Dan Ariely’s second book – The Upside of Irrationality.

The IKEA effect

Chapter 3 is about why we overvalue what we make.

- This is a companion bias to the endowment effect, where we overvalue what we own (even if we were given it for free).

Human beings are attachment machines (see self-storage and hoarding for evidence).

Pride of creation and ownership runs deep in human beings. When we make a meal from scratch or build a bookshelf, we smile and say to ourselves, “I am so proud of what I just made!”

What Dan wanted to know was what are the triggers for this feeling?

- How much work do we have to put in?

He starts with the history of “semi-prepared food” – cake and biscuit mixes, introduced after World War 2.

- The biscuit mixes were more popular at first.

One theory was that the cake mixes simplified the process to such an extent that the women did not feel as though the cakes they made were “theirs.”

Biscuits and pie crusts are not an entire course of a meal, so didn’t feel as much like cheating.

- Marketing experts worked out that letting women add an egg to the mix (along with milk) would fix the problem – this is known as the “egg theory”.

According to Sandra Lee, the “70/30 Semi-Homemade® Philosophy” explains that cooks need to add 30% of the ingredients in order to take ownership.

Dan decided to investigate whether the IKEA effect was based on sentimental attachment or self-delusion (that self-made goods really are the same as expensive shop-bought versions).

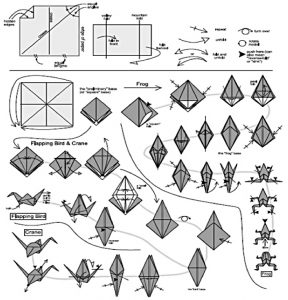

Subjects were invited to make origami animals and then bid for them in an auction – against a computer.

- They would bid first, and then the computer would make a random bid.

Like the eBay auction mechanism, if they bid higher than the computer they paid the price bid by the computer.

- This “second bid” mechanism makes it in the bidder’s interest to bid their true maximum.

Controls did not make the origami animals, they just bid for them.

The average creator bid was 23 cents.

- Controls bid 5 cents on average.

Dan then repeated the experiment with expert origami folders.

- Now controls bid 27 cents for the animals.

Creators had a substantial bias when evaluating their own work.

Dan discusses customisation as a possible route to making consumers love the products they buy.

- This is a factor in new car options, but it hasn’t taken off in the realm of clothing to the extent that Dan anticipated.

There is a delicate trade-off between effortlessness and investment. Ask people to expend too much effort, and you can drive them away; ask them for too little effort, and you are not providing the opportunities for customization, personalization, and attachment.

So the IKEA level of investment seems about right.

Dan repeated the experiment with Lego sets, in order to remove the scope for individual variation.

- Creators were still willing to pay much more for their item, even though it was identical to everyone else’s.

So effort along translates into ownership – customisation is the icing on the cake.

Dan moves on to children.

- As any non-parent will be aware, breeders have a very high opinion of their children, even when it is at odds with the facts.

To investigate whether parents (and others in similar situations) are aware of this over-valuation, Dan compared the results of second-price (eBay style, as above) and first-price auctions.

- In a first-price auction, you need to think about how others will value the item, not just your own valuation.

If creators were aware of their overvaluation of their item, they would bid more in the second-price auction.

- If unaware, they should bid the same under both conditions.

They bid the same, which means they thought that others loved their work as much as they did.

Completion

During his recovery from his burns, Dan made a lot of objects as part of his occupational therapy.

- He grew very attached to the items he completed but did not love those which proved beyond his limited dexterity at the time.

So he wondered if it might be necessary to complete an object in order to over-value it.

Dan repeated the origami experiment, but this time he removed the top strip of the instruction sheet to make things harder.

- Some people got the easier sheet and others the harder one.

About half of the latter group did manage to make an origami animal.

We found that those who successfully completed their origami in the difficult condition valued their work the most, much more than those in the easy condition.

In contrast, those in the difficult condition who did not manage to finish their work valued their results the least, much less than those in the easy condition.

These results imply that investing more effort does, indeed, increase our affection, but only when the effort leads to completion.

Dan draws four conclusions:

- The effort that we put into something does not just change the object. It changes us and the way we evaluate that object.

- Greater labour leads to greater love.

- Our overvaluation of the things we make runs so deep that we assume that others share our biased perspective.

- When we cannot complete something into which we have put great effort, we don’t feel so attached to it.

Dan advises against paying people for services that we could learn to provide for ourselves and enjoy as well.

- I think this is a great lesson to draw from the experiments.

Not invented here

Chapter 4 examines why we fell that our own ideas are better than those of others – the the “Not-Invented-Here” (NIH) bias.

- Dan has struggled to get bankers to adopt his ideas on how to encourage savings.

I began to wonder if the lack of excitement on their part was due to the fact that the idea was mine rather than theirs. Should I try to get the executives to think that the idea was their own or at least partially theirs?

Dan’s experiment asked New York Times science blog readers to consider three problems, and generate solutions to them:

- How can communities reduce the amount of water they use without imposing tough restrictions

- How can individuals help to promote our “gross national happiness”?

- What innovative change could be made to an alarm clock to make it more effective?

Participants were asked to rate their own solutions on practicality and probability of success.

- They were also asked how much time and money they would put it to promote their ideas.

The controls looked at the same problems but evaluated solutions generated by the experimenters.

Participants rated their own solutions as much more practical, as having a greater potential for success, and so on. They also said that they would invest more of their time and money into promoting their own ideas rather than any of the ones we came up with.

Perhaps the NIH observations could be explained by “idiosyncratic fit” – solutions tailored to the creators’ beliefs.

A follow-up experiment used six questions and asked each participant to act serially as a creator and as a control (on three questions each).

- Problem 1: How can communities reduce the amount of water they use without imposing tough restrictions? Proposed solution: Water lawns using recycled gray water recovered from household drains.

- Problem 2: How can individuals help to promote our “gross national happiness”? Proposed solution: Perform random acts of kindness on a regular basis.

- Problem 3: What innovative change could be made to an alarm clock to make it more effective? Proposed solution: If you hit snooze, your coworkers are notified via e-mail that you overslept.

- Problem 4: How can social networking sites protect user privacy without restricting the flow of information? Proposed solution: Use stringent default privacy settings, but allow users to relax them as necessary.

- Problem 5: How can the public recover some of the money wasted on political campaigning? 111 Proposed solution: Challenge candidates to match their ad spending with charity contributions.

- Problem 6: What’s one way to encourage Americans to save more for retirement? Proposed solution: Just chat around the water cooler with colleagues about saving.

To make subjects feel they had created their own solutions, for three questions they were given a list of 50 words that included Dan’s solution plus some synonyms.

The words from Dan’s solution were placed at the head of the list.

- A simpler condition was also included, which simply recorded the words in Dan’s solutions and asked subjects to unscramble them.

Each of these scenarios was sufficient to produce ownership of “their” solutions.

- Idiosyncratic fit is not necessary.

Dan explains that NIH even pervades science.

- Edison was so protective of DC that he ignored Tesla’s arguments that only AC could provide what was needed for the extensive adoption of electricity.

Edison set out to discredit AC as dangerous, which indeed at the time it was.

He began by electrocuting stray cats and dogs, then a sheep.

- Eventually, he invented the electric chair.

And still AC prevailed.

NIH is a real problem for companies, especially “institutions” with a long history.

- I saw this first hand at the BBC, where a lot of very average people were convinced that they were world-class, and industry-standard solutions were regularly rejected in favour of reinventing the wheel in-house.

Dan uses acronyms as an example:

Acronyms confer a kind of secret insider knowledge; they give people a way to talk about an idea in shorthand. They increase the perceived importance of ideas, and at the same time they also help keep other ideas from entering the inner circle.

NIH is also partially responsible for companies that lead during one technical wave failing to make the leap to the next one (Sony not inventing the iPod and missing out on flat-screen TVs, or Kodak ignoring digital cameras).

Once we are addicted to our own ideas, it is less likely that we will be flexible when necessary (“staying the course” is inadvisable in many cases).

This sense of ownership underpins the worst mistake in investment – hanging on to losers.

Revenge

Chapter 5 looks at what makes us seek “justice”.

Dan speculates that the threat of revenge was an effective deterrent in ancient societies.

- Today we (are forced to) outsource that threat to the state.

This is the biblical “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”.

To investigate our desire for revenge, Dan describes the Trust Game.

- Here you are given $10, which you can send to another participant (in a separate room) or keep for yourself.

If you keep it, you each get $10.

- If you send it over, the pot is increased to $50, which the other participant can keep (along with their original $10) or split with you ($25 each).

So trusting the other guy can give you a $15 boost or a $10 loss.

- Rational economics suggests that no-one would send back $25 and so you should stick with your $10, but many people trust and a lot of them have their faith rewarded (Dan doesn’t supply percentages).

The variation on this game that Dan likes involves a third step, where you can use your own money to punish a “cheating” partner.

- For every $1 you donate from your own pocket, $2 is taken from your partner (of course, rational economics suggests that no-one would do this).

In fact, subjects do pay to punish, and simultaneous PET scans of their brains suggest that the decision provides pleasure to the punishers.

- Punishment behaviour has also been demonstrated in chimps (though the experiment that Dan quotes does not impose a cost to the chimp carrying out the punishment).

Trusting societies have tremendous benefits over nontrusting societies, and we are designed to instinctively try to maintain a high level of trust in our society.

This is why we get so upset when the social contract is violated – and why we are willing to spend our own time and money, and sometimes take physical risks, to punish the offenders.

Dan includes a section here on the “rage” felt by “progressives” when the 2008 banking bailout was unveiled – and the “petty and childish” retribution they proposed.

We entrusted those bankers with our retirement funds, our savings, and our mortgages. Essentially, they walked away with the $50. As a consequence, we felt betrayed and angry, and we wanted the bankers to pay dearly.

I don’t see eye-to-eye with Dan on the credit crunch.

- The core problem was bad debt, and the ability of lenders to sell on their credits (and to mix bad debts in with the good, tainting the whole pot).

I’m a fan of less credit and no credit for people unlikely to repay, but that’s not an idea that progressives would go for.

- I find it interesting that in their eyes, bankers need to be held responsible for their mistakes, but ordinary people (who got into debt they couldn’t repay) should be forgiven.

I don’t like bailouts, but I make an exception for the global financial system since without it we would be back to the stone age.

After a poor experience with Audi customer support following a car breakdown, Dan wanted to design an experiment to investigate revenge.

In order to make the experimental subjects want revenge on the experimenter:

We decided to have the experimenter pick up his cell phone in the middle of explaining a task, talk to someone else for a few seconds, hang up, and, without acknowledging the interruption, continue explaining the task to them from the place where he had left off.

The experiment involved an actor in a coffee shop, and the experiment we saw earlier that involved finding pairs of Ss.

- Controls didn’t see the (fake, 12-second) interrupting phone call.

The opportunity for revenge was provided by the actor counting out too much money to pay the subjects ($6 to $9, rather than five), then wandering off to find another participant while the first subject signed a receipt (stating a $5 payment).

The amount of extra money participants received ($1, $2, or $4) had no impact on their tendency to turn a blind eye to the extra cash.

But the interruption did.

A mere 14 percent of the participants who experienced Daniel’s rude side returned the additional money, compared to 45 percent of those in the no- annoyance condition.

Agents and Principals

Dan explains that in a restaurant, the waitress acts as an agent of the principal (the owner).

- If the waitress makes a mistake, you can seek revenge by leaving a smaller tip.

But if the bill undercharges you, accepting this mistake punishes the principal, not the agent.

- And what if the waitress is also the owner?

To test the impact of this agent/principal status, Dan repeated the revenge experiment with the actor, this time getting him to explain that he had been hired by an MIT professor.

- Now keeping the extra money was stiffing the principal, not the agent who caused the annoyance.

We found that the tendency to seek revenge did not depend on whether Daniel (the agent) or I (the principal) suffered. It seems that at the moment we feel the desire for revenge, we don’t care whom we punish – we only want to see someone pay.

With the rise of outsourcing and subcontracting, Dan finds this a worrying result.

Sorry

Dan repeated the coffee shop experiment with a third condition – an apology.

As Daniel [the actor] was handing the participants their payment and asking them to sign the receipt, he added an apology. “I’m sorry,” he said, “I shouldn’t have answered that call.”“The amount of extra cash returned in the apology condition was the same as it was when people were not annoyed at all.

Dan says that “sorry” completely counteracts annoyance, and he supplies a magic formula:

1 annoyance + 1 apology = 0 annoyance

Note that Dan only thinks works for one-off annoyances – you can’t go around acting like a jerk and saying sorry straight afterwards.

The other remedy that Dan discovered was time.

- Even adding 15 minutes before they received the cash they could use for revenge meant that subjects handed more back.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re half-way through the book, so there will be two more articles in this series (along with a summary).

I’m still looking for the upside mentioned in Dan’s title.

- Until next time.