The Honest Truth 4 – Infection, Collaboration and Semi-Optimism

Today’s post is our fourth visit to Dan Ariely’s third book – The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

Contents

Infection

Chapter 8 looks at how we catch the “dishonesty germ”.

- After the 2008 financial crisis, Dan came to the conclusion that the frequency of financial scandals (Enron, WorldCom, Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae and Madoff) was increasing, and he wondered why.

Was this due to improvements in the detection of dishonest and illegal behavior? Was it due to a deteriorating moral compass and an actual increase in dishonesty? Or was there also an infectious element to dishonesty?

He began to read up on infection and bacteria.

We have innumerable bacteria in, on, and around our bodies. As long as we have only a limited amount of the harmful bacteria, we manage rather well.

The problems come from too many bad guys or a particularly nasty bad guy.

The natural balance of social honesty could be upset if we are put into close proximity to someone who is cheating. Perhaps observing dishonesty in people who are close to us might be more “infectious”.

So parents are obviously an influence on children (though work by the Freakonomics team would suggest that peer groups are also crucial).

- But also:

If we see a colleague walking out of the office supply room with a handful of pens, do we immediately start thinking that it’s all right to follow in his footsteps?

Dan suspected a slower process of moral erosion was at work. (( As I write, this moral erosion fits well with the “viral load” theory of Covid-19 infection which is currently popular.

Dan and a colleague used a vending machine to investigate these ideas.

- Some (candy) slots were marked with a 30% discount, whilst others gave you a 70% chance of paying full price and a 30% chance of paying nothing.

These two options have the same expected value, but the second option had greater variability (risk) and so rational people should prefer the first option.

- Of course in practice, people love the idea of something for nothing and the second option tripled Dan’s sales.

In the next experiment, the machine was marked as charging 75 cents per candy, but actually gave a complete refund of the inserted coins.

- There was a number to call if the machine malfunctioned, and a research assistant observed the subjects whilst ostensibly working on a laptop nearby.

Most people tried the machine for three candies, but no-one took more than that.

- And the majority of people invited a nearby friend to get free candy, too.

When we do something questionable, the act of inviting our friends to join in can help us justify our own questionable behavior.

Since they do the same thing, it must be socially acceptable.

Cheating in Class

Dan asked a class to take an honesty pledge not to use their laptops for Facebook and email during his lectures.

- He noted that as a semester wore on, more and more students used their laptops for non-class activities (whilst watching videos on the main screen).

Once the class was in darkness and one student used his laptop for a non-class-related activity, many of the other students, could see what he was doing. That most likely led more students to follow. The honesty pledge was helpful in the beginning, but ultimately it was no match for the power of the emerging social norm.

One Bad Apple

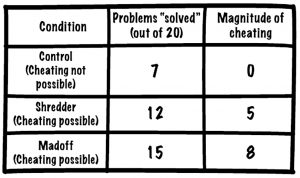

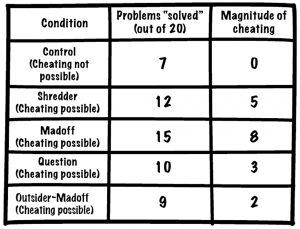

The next experiment repeated the matrix test but with the money given at the start in an envelope.

- Subjects had to leave “change” for the number of answers they got right.

The change (in the envelope) was tossed in a box near the exit door, so cheating was easy.

- As usual, those in the shredder condition cheated.

The next run of the experiment – which Dan calls the Madoff condition – involved a stooge who claimed to have finished the test (all 20 questions) after just one minute.

- Obviously, he was cheating, but the experimenter lets him get away with it, and take all the money in his envelope.

This boosted cheating from 5 extra matrices to 8.

Those in the Madoff condition paid themselves for roughly double the number of answers they actually got right.

Since the Madoff condition includes a signal that cheaters won’t be caught, Dan wanted to be sure that this wasn’t the SMORC theory (cost-benefit analysis) in action.

- He thought that the stooge’s action was a signal that cheating was socially acceptable (new moral boundaries).

The next version of the experiment had the stooge clarify that it would be acceptable to just say you solved everything and take the money (“You can do whatever you want”).

- But in this “question” condition, the stooge didn’t provide an actual social example of cheating.

In the question condition, our participants claimed to have solved an average of ten matrices.

This is two less than the shredder condition and five fewer than the Madoff condition.

- So the social cue is much more important than the reduce chance of capture, and the stooge’s question actually reduced cheating (vs. baseline shredder).

When we become aware of the possibility of immoral behavior, we reflect on our own morality. And as a consequence, we behave more honestly.

Dan has shown this previously with the Ten Commandments and honour code experiments.

In the next variation, the stooge wore an “outsider” T-shirt with the logo of a rival university but behaved as in the Madoff condition.

- Would the subjects be influenced less by someone not from their group?

In the outsider-Madoff condition, the students claimed to have solved only nine matrices.

That’s still cheating, but only by two, and six less than the regular Madoff condition.

As long as we see other members of our own social groups behaving in ways that are outside the acceptable range, it’s likely that we will recalibrate our internal moral compass. If the member of our in-group happens to be an authority figure – a parent, boss, teacher – chances are even higher that we’ll be dragged along.

As usual, Dan takes the opportunity to generalise these findings to financial services.

Fudging the numbers now becomes accepted behavior, at least within the realm of “staying competitive” and “maximizing shareholder value.”

He also takes a pop at the US congress, and the use of PAC money.

- Finally, he discusses the essay mills used by unscrupulous students (which he shows are of a low standard).

I do worry about the existence of essay mills and the signal that they send to our students – that is, the institutional acceptance of cheating.

Solutions

Dan talks about the Broken Window Theory, which suggests that not fixing small problems sends a signal that they will be tolerated, and leads t more small problems, and then eventually to bigger problems.

- I think that’s a great approach, but that ship has sailed, politically.

Of course, Dan only wants to apply the theory to “those in the spotlight: politicians, public servants, celebrities, and CEOs.

- In this context, he’s a big fan of whistleblowers, and the positive signal they send about what society finds acceptable.

I find it hard to share Dan’s conviction that white-collar crime is the worst crime.

- I’d like the muggers and burglars and drug-runners on my street sorted out.

Collaborative Cheating

Chapter 9 is about why two heads are not always better than one.

In general, people tend to believe that working in groups has a positive influence on outcomes. In fact, much research has shown that collaboration can decrease the quality of decisions.

I’ve never been taken in by the idea that groups are better than individuals.

- But then perhaps I’ve just been unlucky with the groups that would have me as a member.

Dan looks at the ambiguity inherent in the accounting process, and the scope for bending the rules.

- In many workplace situations, “cheating” (however loosely defined) takes place within a team.

When we are part of a group, are we tempted to cheat more? [Or] less?

Dan is moving the discussion from the social contagion of the last chapter into situations of social dependency.

- What do we do if the (eg. financial) welfare of others depends on our actions?

Social utility

Social utility is used to describe the irrational but very human and empathetic part of us that causes us to care about others and take action to help them out when we can – even at a cost to ourselves.

This covers things like handing in a lost wallet or helping with a flat tire.

- I would offer the caveat that such things only really count when there is a real cost to us, and when nobody is looking – virtue-signalling is another thing entirely.

Social utility can also induce us to cheat when it will improve the welfare of those around us.

Eyes on us

On the other hand, it may be that we don’t cheat when others will see, and in this context, the other team members as extra pairs of eyes, making it less likely that we will cheat.

- Dan quotes an experiment where the sign over the honesty box in a university tea-room was decorated with either images of flowers or of eyes looking at the drinkers.

When the glaring eyes were “watching,” the box contained almost three times more money [at the end of the week].

Collaborative shredding

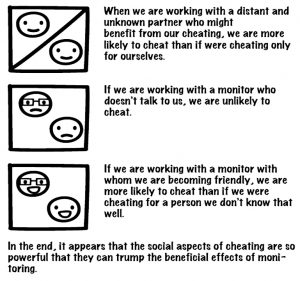

To test these opposing forces, Dan and his colleagues re-ran the matrix experiment with a collaborative shredding condition.

The experimenter tells you that you are part of a two-person team and that each of you will be paid half of the group’s total earnings.

Answer sheets were either blue or green, and subjects had to pair up with whoever had the sheet of the opposite colour, but with the same number in the corner.

- At the end, you write your partner’s score as well as your own on the sheet and total them.

When participants learned that both they and someone else would benefit from their dishonesty, they [claimed] to have solved three more matrices than when they were cheating just for themselves.

That we will cheat “altruistically” for someone we barely know is bad news.

In the next version, the two team members worked in series, each watching the other work.

Being closely supervised eliminated cheating altogether.

In the next stage, participants asked each other questions to get to know each other a bit, before monitoring each other in series.

- Sadly this led to four matrices’ worth of cheating.

Altruistic cheating overpowers the supervisory effect in a setting where [people] have a chance to socialize and [then] be observed.

In a final condition, only your partner would benefit from your cheating.

When cheating was carried out for purely altruistic reasons and the cheaters themselves did not gain anything from their act, overclaiming increased to an even larger degree. When only other people stand to benefit from our cheating, we find it far easier to rationalize our bad behavior in purely altruistic ways and further relax our moral inhibitions.

Dan also notes that performance across the control groups for all these conditions was flat.

It seems that performance doesn’t necessarily improve when people work in groups.

Long-term relationships

Next Dan looked at long-term relationships with conflicts of interests (doctors, accountants, lawyers, financial advisors).

- We know that people are more likely to trust their advisors the longer they have known them.

But as these advisors get to know you better, will they look out for your interests more?

- Or will they become more comfortable in recommending courses of action which are in their own best interests?

Dan and his colleagues looked at this question using dental records from millions of procedures over 12 years.

- They compared silver fillings (cheaper, more durable) to white composite (more expensive, better cosmetically).

So a rational person would go white at the front, silver at the back.

A quarter of all patients receive attractive and expensive white fillings in their hidden teeth. This tendency is more pronounced the longer the patient sees the same dentist.

So the dentist is more comfortable pushing expensive fixes.

- And the long-term patient is more receptive to taking this bad advice.

Solutions

Since collaboration increases dishonesty, Dan would like to see more monitoring.

- This is the default response to financial corruption (Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank etc), but more regulation also impacts efficiency and innovation (and costs).

Dan prefers the approach taken in an experiment run by a former student of his, where loan officers’ work was reviewed by an outside (disconnected) group which had no motivation to help the loan officers.

- Because of confidentiality, Dan doesn’t know for certain that it worked.

But assuming it did, it will also have lessened the fun of the work, and added to its stress.

That was a common thread throughout my working career – less freedom and control, more monitoring and regulation.

- Eventually the job isn’t worth the money they pay you to do it.

Semi-Optimism

In Chapter 10, Dan suggests that people don’t cheat enough.

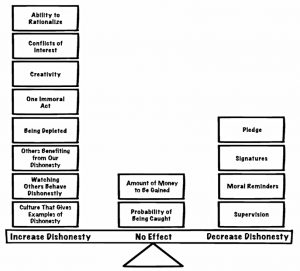

The theme of the book is that dishonesty is governed by two opposing forces:

- We want the spoils of cheating

- But we also want to think that we are nice people.

This sounds like having the cake and eating it, which is where Dan’s fudge factor comes in.

- We cheat a bit, gain a bit, and still think we are good.

Money and being caught have less influence than we might expect.

- Moral reminders, conflicts of interest, depletion, myth-making, creativity, caring about others and watching another cheat all seem to matter more.

The good news is that rational economics would expect us to cheat more than we do.

- That’s what Dan means by we don’t cheat “enough”.

Real cheaters

In the matrix experiment, we have never seen anyone claim to solve eighteen or nineteen out of the twenty matrices. But once in a while, a participant claimed to have solved all twenty matrices.

This is the rational actor, or as Dan would like to characterise the “the real criminal”.

- But there aren’t many of them so they don’t impose much of a cost.

We had thousands and thousands of participants who cheated by “just” a few matrices, but because there were so many of them, we lost thousands and thousands of dollars to them – much, much more than we lost to the aggressive cheaters.

It is probably more important to discourage the small and more ubiquitous forms of dishonesty.

Cultural differences

To test whether people from different cultures cheat to different extents, Dan needed a common payment incentive.

- In a spin on the Economist’s Big Mac Index, he used a “beer index”.

We set up shop in local bars and paid [sober] participants one-quarter of the cost of a pint of beer for every matrix that they claimed to have solved.

Dan tested in Israel, China, Italy, Turkey, Canada and England.

The amount of cheating seems to be equal in every country. How can we reconcile [this] with the clear differences in corruption levels among countries, cultures, and continents?

Dan thinks this is because the matrix test exists outside any cultural context.

It tests the basic human capacity to be morally flexible and reframe situations and actions in ways that reflect positively on ourselves.

The cultural context will determine where activities start out on a moral continuum, and how much fudge factor is acceptable.

- At American universities, plagiarism is taken very seriously, but in other cultures, it is viewed as a kind of poker game between the students and faculty.

Getting caught, rather than the act of cheating itself, is viewed negatively.

- There are similar attitudes to taxation, to running red lights, or to affairs in some countries.

Solutions

As before, Dan recommends reminders at the moment of temptation, which are surprisingly effective.

- We also need to do much more about conflicts of interest (or as I would prefer to call them, mismatched incentives).

Dan also recommends the implementation of recommendation from Broken Window Theory (good luck with that one).

- And we should all watch out for the impacts of physical and mental depletion.

Dan also makes the case for “resetting rituals” common to the major religions.

- The Catholic confession is the one I’m most familiar with, and I have to say that it did nothing for me.

Secular equivalents include New Year’s resolutions, birthdays, changes of job, and romantic breakups.

- The idea behind all these is to reverse the “what-the-hell” effect, from which I have personally only suffered in the short term (eating and/or drinking too much on a single day).

Maybe we should get our public servants and businesspeople to take an oath, use a code of ethics, or even ask for forgiveness from time to time.

Once again, good luck with that – with my cynical hat on, I suspect that the people who seek these positions are the ones that Dan likes to call “real criminals”.

Self- flagellation

Dan and his colleagues decided to investigate a bloodless form of the self-flagellation purifying ritual used by Catholic sect Opus Dei (as seen in the Da Vinci Code.

- They used mildly painful electric shocks instead.

One group of subjects was asked to write about something that made them feel guilty.

- A second group had to write about something which made them feel sad.

- And a third group had to write about a neutral memory.

In phase two, subjects were asked to inflict increasingly strong electric shocks upon themselves, until they could not tolerate more intensity.

In the neutral and sad conditions, the degree of self-inflicted pain was similar and rather low. Those in the guilty condition were far more disposed to self-administering higher levels of shocks.

So Opus Dei is on to something.

Truth and reconciliation

Dan tells the story of a woman in South America whose maid was stealing meat.

- She put a lock on the freezer, told the maid that stealing was going on, then gave the maid the second key to the lock (and a small pay rise).

By locking the freezer and giving the maid an additional responsibility, the [woman] offered the maid a way to reset her honesty level.

Trusting the maid with the key was an important element in establishing the social norm of honesty in that household. Any act of stealing would have to be more deliberate, more intentional, and far more difficult to self-justify.

Dan mentions the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa as an example of a similar process, but I have to regard the transition from apartheid as a failure.

The corresponding commission in Northern Ireland had appeared to be more successful.

- But the recent divisions over Brexit, and the increasing popularity of Sinn Fein south or the border have revealed it to be less so.

Conclusions

Dan concludes:

Dishonesty is a prime example of our irrational tendencies. It’s pervasive; we don’t instinctively understand how it works its magic on us; and, most important, we don’t see it in ourselves.

That much is true, but how to go about fixing it is less clear.

That’s it for today – we’ve finished the book.

- I’ll be back with a summary of the four articles in this series in a couple of weeks.

Until next time.