Resolution Foundation Tax Proposals 2023

Today’s post looks at a recent report from the Resolution Foundation on Tax Planning.

Contents

Tax Planning

The Resolution Foundation (RF) is a left-wing think tank that produces a lot of reports, several of which we have reviewed on this blog.

- Their thinking on tax tends to be fairly extreme, and so I often take no notice, particularly under a nominally Tory government.

But by the end of next year, there’s a fair chance that Labour will be in power, and they might listen more closely to the RF.

- Forewarned is forearmed, so let’s take a look at their recommendations.

The 88-page report came out in June 2023 and is called “Tax planning – How to match higher taxes with better taxes”.

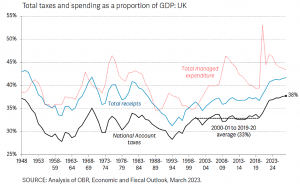

- So right up front, we can abandon all hope of tax cuts, despite the UK tax burden already being at a peacetime high.

The problem

The report admits as much, but is not happy:

From an average of 33 per cent of GDP over the 2000s and 2010s, the UK’s tax take is forecast to approach 38 per cent by 2027-28. But this increase in the quantity of taxation has not been matched by an increase in its quality.

There have indeed been a lot of U-turns in recent years.

The same taxes have been slashed and then surged, while well-understood problems with our tax system have been reinforced rather than addressed.

Problem taxes

Corporation Tax has been a great source of policy uncertainty, going from a standard rate of 28 per cent in 2010 to 19 per cent in 2017 (and a pledge to go to 17 per cent), only to rise back to 25 per cent in 2023, alongside frequently changing investment allowances.

It’s a good example, but my view is that UK corporation tax needs to be lower than that of our competitors (in particular, in the EU) so that we can attract foreign investment.

The existential challenge to Fuel Duty posed by electric vehicles has been ignored, while we have spent the last decade with a policy of raising it in line with inflation and a reality of that rise being cancelled every year.

Grasping the nettle on fuel duty (per-mile charging) would have risked putting even more people off electric vehicles (as if range anxiety, roadside repair, resale values and a lack of charging infrastructure weren’t doing a good job already).

Other taxes that RF see as problematic include:

- Council Tax, which is now rising relative to incomes as council budgets come under strain (but which is difficult to reform with a severe bias against London and the South East)

- National Insurance, which has been hiked to get around pledges on income tax freezes, but which introduces a bias against employment

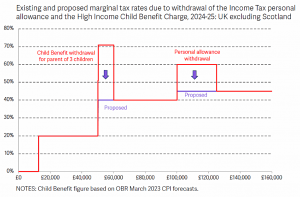

- Marginal rate inconsistencies from the withdrawal of child benefit and the personal allowance

The solution

RF claim that minor tweaks will make a big difference:

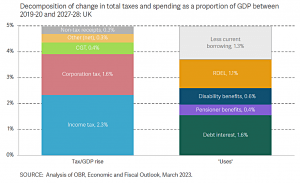

Replacing parts of the tax system worth over 1 per cent of GDP with roughly equivalent increases elsewhere – demonstrates that it is possible to focus on the quality, not just the quantity, of tax.

But at the same time, taxes are heading higher:

The right reaction to taxes reaching a seven-decade high for structural reasons [low growth, poor demographics] is not to pretend a major tax-cutting era is just around the corner, but to focus on improving the economic efficiency, equity and predictability of the tax system.

The broad strategy that RF want to follow is raising growth and lowering inequality.

- I think that’s a very difficult combination to pull off, and I am more concerned with the former than the latter.

Inequality means different things to different people, but it’s a fact that even the poorest in the UK are very rich in global terms.

- Bleating about national inequality but ignoring global inequality make no sense, but there would clearly be no support in the UK for an agenda which targeted bringing us down to the global average.

Taxes should fall first on externalities such as pollution and congestion, and favour the taxation of land or housing that is in relatively fixed supply.

This sounds attractive, but the devil is in the detail.

- The former category of tax often disproportionately affects the poor (as with London’s ULEZ and congestion charges) and the latter amounts to a wealth tax.

RF also want to target transaction taxes, which is fine by me.

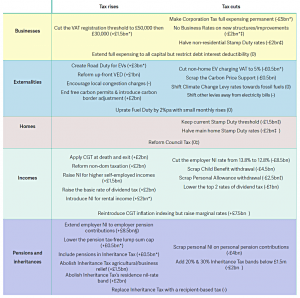

Here’s a summary table of the proposals:

Supporting growth

The first measure here is to make full expensing of plant and machinery permanent (it’s due to end in March 2026).

The objective is to increase the level of investment and not just bring forward its timing.

RF would extend the allowance to buildings, and they have a neat way of funding it:

Costs could be offset by reducing the limit on how much interest is tax deductible by a firm, thereby reducing the bias towards debt financing in the tax system.

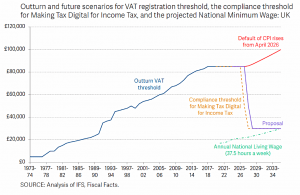

They would also make Corporation tax rates and allowances “stable”, and would lower the VAT threshold to £30K pa.

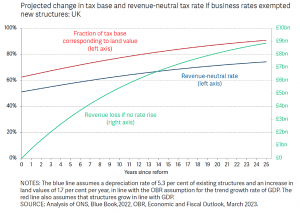

They would also reform business rates:

Reform should exempt new structures and improvements from the base of business rates so that it gradually becomes a land tax, but while avoiding a windfall for current landowners.

Property

This is a big one for most investors, who will own a fair bit of property.

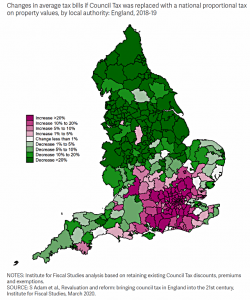

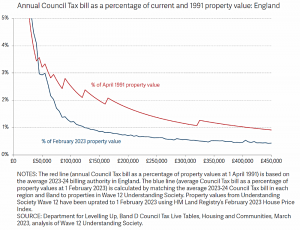

Council Tax needs a complete overhaul. Revaluations are needed and values should then be updated annually to avoid repeating a history of revaluation delays. Council Tax should also move away from its internationally-unusual banded approach to a fully proportional tax on property values.

This makes it a stealth version of a wealth tax – renters and those in social housing will dodge the bullet.

- Given the huge regional disparities in valuation (my somewhat larger house is worth ten times the price of the one I grew up in), I’d like to see a property tax based on square footage rather than value.

This change will be difficult to implement:

- valuations are notoriously difficult to pin down,

- and a big bang implementation would chop six-figure sums off many house prices,

- and lead to a lock-up in the housing market (as well as putting recent buyers underwater with their mortgages).

RF has a potential solution:

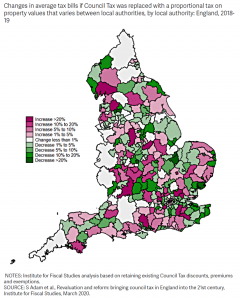

These key goals of revaluation and proportionality can be delivered without major overnight redistribution of tax burdens across councils: they should be done in a way that initially [my empahsis] affects only the distribution within council areas, with the implication that different parts of the country would have very different property tax rates.

That might work, though it introduces the same problems in microcosm:

- London boroughs have a great spread of taxpayer incomes and property values, and large social housing and privately rented sectors.

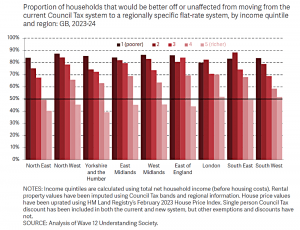

Even with regionally specific Council Tax rates, some people will see very large rises in their bills. Our analysis indicates that around 13 per cent of households would face a Council Tax bill increase of over £500, and 7 per cent would see an increase of over £1,000.

The RF response is to cap the annual increase in Council Tax to £500.

Even allowing for a lower average contribution in London than in Manchester, the top 10% of council taxpayers in, say, Lambeth (where I live) will be paying for everybody else.

- This will provide a great incentive to relocate to a more equitable borough, which will push down the values of the best properties and increase the council tax burden on the layers below.

And it might be only a stay of execution:

A separate, more gradual, convergence is then needed via the local government finance settlement process – which is already overdue a review – with English council funding calculations gradually shifted from a 1991 Council Tax base to an up-to-date proportional property tax base.

I worry that this means that regional rates would converge over time, or at least that those in expensive houses in the south will be gradually milked for all they can bear.

Local authorities with larger tax bases would be able to set lower tax rates than those with smaller tax bases. A household occupying a £350,000 property in the North East would be charged a higher tax rate than an equivalent household in the South East.

The final step in reforming Council Tax should be to close these differences by adjusting the local government finance settlement process to better reflect each local authority’s tax base.

I suppose it’s plausible that this reform would hit the prosperous South East more than the very diverse London boroughs.

RF also want to fix stamp duty:

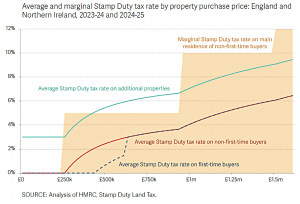

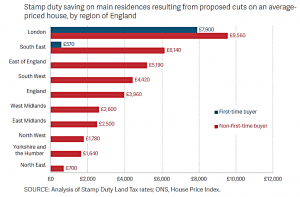

Stamp Duty Land Tax is a bad tax. By making it more expensive to move, it results in a sub-optimal allocation of housing, and subsequently also affects the labour market by reducing workers’ effective options.

So, scrap it then? No.

The Stamp Duty threshold [temporarily at £250K] should be made permanent, and Stamp Duty rates for main homes should be halved.

This would bring down the cost of moving in London from £150K to £75K – not too much to cheer about there.

Incomes

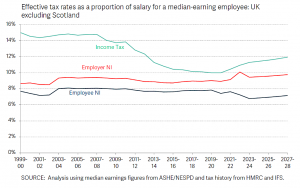

On income, the RF focus is on the variability of marginal rates.

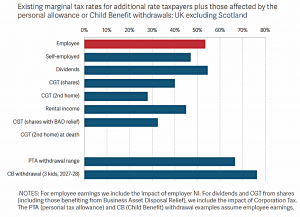

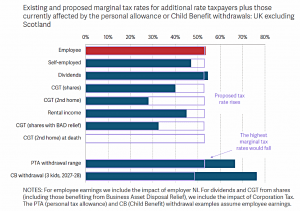

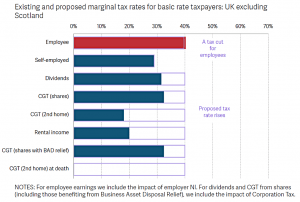

The top marginal tax rate for employees’ wages is 53.4 per cent when employer National Insurance (NI) is accounted for, and corporate dividends are taxed at similar levels – up to 54.5 per cent when the main rate of Corporation Tax is included.

But:

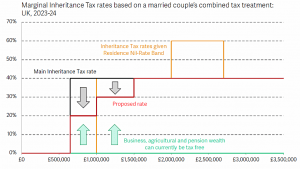

Marginal tax rates faced by individuals can be far lower or far higher than this, ranging all the way from zero or 10 per cent for some large capital gains, to 28 per cent for private equity managers, to 67 per cent for employees facing the withdrawal of the personal allowance, to over 100 per cent for some parents.

The underlying beef is that employees pay more than those who take “income” in other ways, largely because of NI, which only applies to wages.

RFs proposals are:

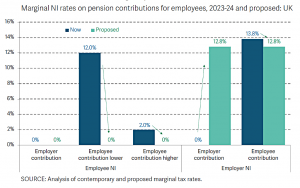

- cut employer NI to 12.8%

- increase the basic rate of dividend tax to 20% and cut the higher rates by 2%

- (re)introduce inflation indexing to CGT, but raise the CGT rates (on shares) to match those on dividends (with a new top rate of 37%)

- CGT on property should match that on wages, at between 40% and 53%

- Rental income should attract NI (at 20% for basic rate payers and 8% for higher rates, phased in at 2% pa)

- Self-employment income would have the same NI rates as property, but only the higher-rate band is a priority

- The exception of gains from CGT on death would be abolished

- The withdrawal of the Personal Allowance and of Child benefit would be abolished

The end result of these changes would be that incomes from employment, self-employment, dividends, real capital gains and rents would all face almost identical marginal rates of tax.

The top rate would be 53%, the middle rate 48% and the “lower” rate 40%.

Wealth

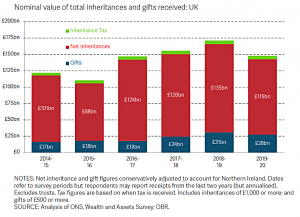

Given the UK’s large and primarily passive rise in wealth levels relative to GDP, which has created patterns of winners and losers based to a great extent on luck – such as large swings in interest rates or being born to the right parents – policy should aim to raise more revenue overall from these wealth-related taxes, but reform is also needed within them.

I can’t say I feel lucky myself – the outperformance by me of my peer group is largely down to individual choices – but let’s see what’s in store.

The proposals are:

- add NI to employer pension contributions but add NI relief to personal contributions

- gradually reduce the tax-free pension cap (now £270K) by date of birth

- include pension pots in the IHT calculation

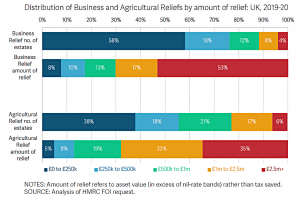

- scrap the Business Relief exemption (which includes AIM stocks)

- abolish the Residence Nil-Rate band

- abolish the exception of gains from CGT on death (as noted above)

- replace the flat 40% IHT rate with bands of 20%, 30% and 40% or replace IHT with a recipient-based lifetime acquisitions tax (as in Ireland)

A few comments on this lot:

- more people will be paying IHT

- pension contributions will switch from companies to individuals (to what end?)

- the AIM market will plummet

- phasing out tax-free lump sums should apply equally to DC pensions (but won’t, because that’s what public sector workers rely on)

Conclusions

To be honest, this isn’t as bad as I was expecting – the new council tax is probably the bitterest/biggest pill to swallow, and the detailed impacts are hard to work out in advance.

- I have an ideological objection to IHT, and so do the majority of voters, but they might still vote for a government that doesn’t.

But there’s no direct mansion tax or wealth tax, and SIPPs, ISAs and VCTs remain intact.

- So most people will be able to cope.

There’s not much mitigation to be done against this package of reforms, except perhaps to sell some property and all your AIM stocks.

- Few will do the former, but we might see some of the latter as the prospect of a Labour government solidifies.

Until next time.