Tax plans

Today’s post looks at the state of the UK’s finances and the implications for future tax changes.

Tax plans

A lot of what I’m discussing today is speculation, and normally I wouldn’t be concerned with it.

- But we have an election looming in the next year or so, and the odds are strongly in favour of a change of government.

This will probably mean a change in the UK tax regime, and it’s worth considering what might happen, just in case there are mitigating steps that can be taken in advance.

The trigger for this post was a newsletter from David Stevenson at the start of September.

- He referenced an article in the New Statesman by Harry Lambert.

The following week he discussed a blog post from Sam Freedman.

- But before we look at what David, Sam and Harry have to say, let’s examine an article in the FT from Martin Wolf.

Martin

Martin would like some candour on taxes.

- No government of any colour can promise tax cuts.

Some individual taxes may fall, but others will rise, and so must the overall tax burden.

Any promise to cut the ratio of tax to gross domestic product permanently and substantially needs a concomitant promise to cut the level or rate of growth of spending. A party could promise to slash spending on health, for example. But could it get elected?

This is the real problem in the UK – spending never goes down.

- Once the public has been given a handout, they want to hang on to it in perpetuity.

I am philosophically opposed to this approach.

- I want to spend my own money as I see fit, and not hand it over to the government so they can redistribute it to less competent members of society.

We need to cut spending so that we can cut taxes.

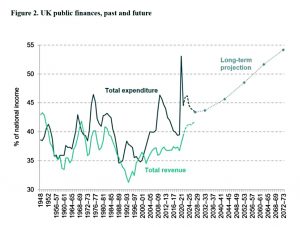

UK borrowing is at its highest since the 40s, debt is at its highest since the 1960s, and thanks to recent rises in interest rates, the cost of servicing the debt is at its highest since the late 80s.

- A quarter of UK debt is held by foreigners, which are likely to impose fiscal discipline (as Truss and Kwarteng found).

We also have a feeble economy, reliant on the financial sector.

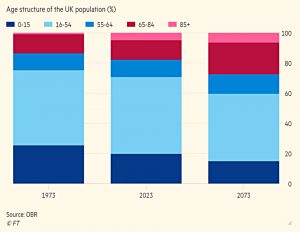

We also have bad demographics (an ageing society), and increased spending commitments on defence and the energy transition (Net Zero).

- Government spending is now 41% of GDP and even as Covid and the energy crises fade, is only expected to fall to 39% by 2027-28.

Increased spending on health, defence and energy means that this number will subsequently rise, along with taxes.

- Martin would like to see the tax base shifted away from work and investment (presumably he means corporate investment here) and onto land and “other forms of wealth”.

It’s hard to know how strongly to oppose this idea without seeing the details, so I’ll merely note that just as income tax discourages work, a wealth tax discourages saving in favour of immediate consumption (and ultimately discourages UK residency).

Martin also believes that the UK is not a highly taxed country.

- Whilst it is true that there are close to a dozen more highly taxed nations, this is not the company I want to be seen in.

All the countries I admire (Japan, Australia, Switzerland, the US and Korea – not to mention Singapore and Hong Kong before China got involved) pay less tax than we do.

David

David Stevenson thinks that Labour’s promises of no tax rises should be taken with a pinch of salt.

There are four taxes that could go up:

- taxes on income, but these are already high

- taxes on corporations have recently risen (Corporation Tax is now an uncompetitive 25%)

- taxes on spending (VAT) but this is regressive, and replacing fuel duty with pay-as-you-drive mileage changes will be difficult enough

- taxes on wealth and property

The pressure to look again at wealth and property taxes will, at some stage inthe next five to ten years become irresistible.

David looks at wealth taxes in more detail when discussing Harry’s article (see below).

- He thinks that is it possible to design a successful wealth tax, though it will pit off entrepreneurial types.

The debate is whether a wealth tax is worth the effort for the reward. I would hesitantly suggest that there is a quiet consensus that it might be better to look elsewhere.

Sam

Like Martin, Sam is worried about the state of the public finances.

By the mid-2040s government will need to spend over 45% of national income on public services, benefits and debt repayments. By the 2070s it will be over 55%.

As before, this is based on health and social care costs, demographics and Net Zero.

Sam notes that over the last 40 years, governments have used lots of tricks to keep the rising cost of the state hidden from taxpayers:

Thatcher and Major did it by using north sea oil money and returns from privatising utilities. Blair and Brown used PFI to keep infrastructure spending off balance sheet.

These governments also benefitted from the “peace dividend” following the fall of the Berlin Wall, and were able to cut defence spending heavily.

Cameron and Osborne tried to hold costs down by cutting all spending other than healthand pensions, while using quantitative easing to keep the economy afloat.

But this can’t continue.

There are no more utilities to privatise. PFI is now on balance sheet. There is nothing left to cut. Health costs rises are inevitable.

Sam’s discussion of the choices available to the next government is behind a paywall, so we must rely on David’s commentary.

He thinks Labour have some wiggle room:

The fiscal rules they have signed up to are a bit looser than the government’s, creating space for more borrowing for infrastructure investment as long as debt is due to fall overall. Reeves has also spoken about using a measure of “public sector net worth” in her rules, which would take into accounts the benefits of investment as well as the costs.

He also thinks that GCT is going up, as rather than specifically ruling this out (as with wealth and mansion taxes), Rachel Reeves has merely said that she has “no plans” for an increase.

Harry

Harry’s (pretty ideological) article takes the view that Labour will have to raise taxes on wealth, even though they have promised not to.

He has four main ideas, designed to raise £28 bn pa, which could be fed back into income tax cuts (or into green energy):

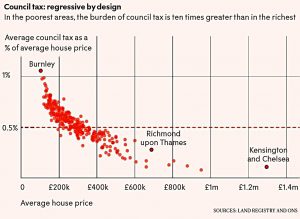

- Flatten council tax to 0.5% across the nation

- Add NICs to landlords and “speculators” (investors?) who “profit without working”

- Equalise capital gains tax with income tax

- A wealth tax of 1% on wealth over £10M

There’s a lot to unpack here.

- Let’s get CGT out of the way first – I have no issue with this one, though I think the annual allowance should be more like £20K pa (minimum wage) than £3K.

NICs are problematic because they are intended to fund the state pension (even if the actual funding mechanism is different), which is a wage replacement for old age.

- So it makes philosophical sense to restrict the tax to wages.

And it would be odd to tax people further who are already of state pension age (as many landlords and “speculators” will be.

A tax of 1 per cent on wealth over £10m would fall on around 20,000 people – the 0.1 per cent.

The wealth tax arguments have been largely covered by David, and whilst the £10M threshold seems fair, 1% pa is most definitely unfair.

- Somebody who hit £10M at age 40 would be shelling out for potentially 50 years, handing over half of their wealth above the threshold.

They might want to live somewhere less hostile than the UK.

If you live in Burnley, you will on average pay 1.1 per cent of the value of your home in council tax every year. If you live in a typical property in Kensington and Chelsea, you will pay 0.1 per cent.

The council tax proposal is interesting.

- It sounds fair, and 0.5% pa seems at the upper range of what might be considered reasonable.

Note that someone like me who bought his first house in his mid-twenties would be paying this tax for 60 years, handing over 30% of his property wealth.

- Which brings us to implementation.

There are two problems:

- Houses are now worth 30% less than they used to be, and we have a housing crisis

- This will apply mostly at the expensive end, where council tax is currently much less than 0.5%.

- The tax on a £1M flat in London is now £5K pa, and on a £2M terraced house it is now £10K pa.

- For many people, these are not reasonable amounts to pay each year, and there will be a wave of selling, exacerbating the housing crisis caused by suddenly lower valuations.

So it would need to be phased in gradually, and there might need to be a roll-up option where the outstanding amount is paid on death or the sale of the property.

Conclusions

The articles are united in thinking that higher taxes are on the way, but despite all four being written by lefties (of various flavours) there’s little in the way of detail or even a general consensus on what might happen.

- Nor is there much advance mitigation available, other than to minimise property exposure and crystallise any capital gains.

Or leave the UK entirely before any of this happens.

For now, my own modest mitigation is to put my plans for a seaside cottage on hold until after the election.

- Until next time.