Stock Returns – The Bessembinder Report

Today’s post is a look at Stock Returns, and specifically the work done by Hendrik Bessembinder, which has been picked up by some active managers as supporting their stock-picking approach.

Stock returns

Everybody knows stocks have the best (long-term) returns of any asset class, and that this has been the case for more than 100 years, though all kinds of economic circumstances.

- But the nature of capitalism’s process of creative destruction means that this positive picture overall hides many disasters.

Not all stocks are created equal, and not all stocks have good returns.

- Some have returns worse than bonds, or even negative returns.

Only a tiny minority of companies have been able to fight off competition and grow large.

- These are typically the stocks that Buffett looks for, the ones with moats.

Of course, some firms just get lucky.

Bessembinder

Professor Hendrik Bessembinder, of the WP Carey School of Business at Arizona State University looked at stock returns in the US from 1926 to 2015.

He looked at the returns on 25,782 listed stocks.

- Only 42% of these had a better return than cash.

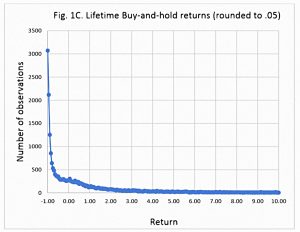

Most stocks do not outperform Treasury bills over their lives.

The average stock was listed for just seven years, and the most common lifetime return was a loss of 100%.

Bessembinder’s paper is called “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?”

- The abstract has the answer:

Most common stocks do not. Slightly more than four out of every seven common stocks that have appeared in the CRSP database since 1926 have lifetime buy-and-hold returns, inclusive of reinvested dividends, less than those on one-month Treasuries.

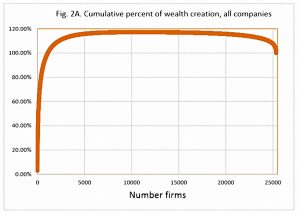

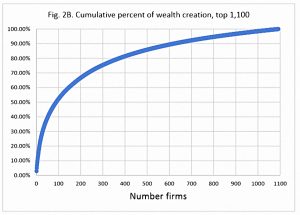

The finding that the industry has picked up on was that just 4% of listed stocks were responsible for all of the positive gains of stocks during the period.

When stated in terms of lifetime dollar wealth creation, the entire gain in the U.S. stock market since 1926 is attributable to the best-performing four percent of listed companies.

Half of the growth was down to 0.4% of stocks (just 86 firms).

Bessembinder found that a greater proportion of large stocks had better returns than cash.

- Listing first on a major exchange (NYSE) and a lack of debt were also positive factors.

He also found that stocks are becoming less and less likely to be winners:

- 72% of stocks listed between 1926 and 1935 were winners.

- By 2006 to 2015, just 42% of the much larger number of stocks listed were ahead.

So should we all become stock-pickers?

- Bessembinder merely states that the rewards are good, if you can pick reliably:

The returns to active stock selection can be very large. Of course, the key question of whether an investor can reliably identify such “home run” stocks, or can identify a manager with the skill to do so, remains.

Active managers

I can’t recall where I first came across Bessembinder’s work, but over the summer I’ve seen three presentations from active fund managers who explicitly referenced it.

The first and most vocal of these was James Anderson, manager of the wildly successful Scottish Mortgage Trust.

- Anderson is understandably keen to attribute the success of the trust to his stock-picking abilities rather than the stellar run of US tech stocks that he is over-exposed to.

Your returns are dominated by a very small number of companies and it’s trying to identify which ones have the possibility of greatness that matters.

You can still be quite diversified and not capture any of these stocks.

I worry that there is a misperception about where returns come from – that it is an asset class that delivers the returns rather than individual companies.

At the presentation I attended, he seemed to be angling for the vacancy recently created by a few years of underperformance from Neil Woodford.

- Anderson appears to be a big believer in the Great Man theory of history, and sees Elon Musk as a visionary rather than a nutjob.

- He also name-drops hanging out with founders like Jack Ma.

Anderson’s story is that “it’s different this time” – we’re entering a period of “even more profound and rapid change” than before, and the benefits will accrue to a very small set of firms.

- So these are the ones to buy, regardless of their current price.

Company characteristics

Anderson went to meet Bessembinder after the publication of his research.

The next stage was to think about what characteristics those 90 winners have in common and what characteristics fund managers might need to be able to exploit them.

Anderson says that the winners were:

- Early entrants to markets that later became huge.

- Founder-run.

- Willing to accept / embrace uncertainty.

The first two points are hard to argue with, other than that there are a lot of founder-run early movers who fail, and it’s hard to identify winners in advance.

- Quantifying the third point is just hard full stop.

Growth

I agree with a lot of what Anderson says about his tech favourites:

- The dominance of the major platforms (Amazon, Google, Facebook, Tencent, Alibaba) could increase from here.

- And regulation could help, since incumbents have deeper pockets with which to fund compliance.

But everything has a price, and we may already be paying too much.

Anderson’s spiel is in effect just the internet 2.0 version of the growth story – and growth doesn’t work.

- Investors pay too much for growth stocks because they ignore the tendency for growth to reduce future profits.

As they expand, firms cut prices to win market share and fend off competition.

- Central costs (of managing and coordinating the company) also rise, and decision-making become slower.

It’s the greater fool approach to investing, without the exit discipline of trend following / momentum investing.

- We’ve seen it before in the railways, the “permanently high plateau” of the 1920s, the Nifty Fifty, Japan and the dot-com boom.

In the end, there’s always someone who overpays and loses money.

Responses

There are three ways in which to react to Bessembinder’s finding:

- The Anderson route – work out (guess) which characteristics will lead to future success, and buy a lot of that kind of thing.

- This is risky, but could produce exceptional short-term results.

- But it’s hard to identify the winners, and the underlying characteristics are likely to change over time.

- So most people won’t be suited to it (which provides an opening for the marketing departments of fund management firms like the one that Anderson works for).

- Make sure that you are well-diversified

- If it’s hard to pick the winners, you need to hold everything, to make sure that you include them.

- This way lies the Vanguard passive approach, and it’s proven to work.

- Identify the characteristics of stocks that underperform, and avoid them.

- If 4% of the market has all the returns, then the bottom 96% is flat (compared to Treasury bills).

- But leave out the bottom 58% (the ones that Bessembinder found did worse than cash), and you’re going to do pretty well.

- You could start by simply excluding the smallest 20% (or more) of stocks.

I advocate a combination of the second and third approaches.

- Diversify widely to pick up the free lunch of better risk- (volatility-) adjusted returns.

- And screen stocks for factors that makes them more likely to appear in the top half (or top quartile) of the return distribution.

Then keep your costs down and take advantage of tax shelters.

Conclusions

Bessembinder’s finding that 4% of stocks hoovered up all the gains is clearly eye catching and memorable.

- But it doesn’t mean what you think it does.

- And it doesn’t have the implications that you think it does.

It doesn’t mean that the other 96% didn’t make money.

- It only means that as a group they didn’t make money.

There’s still plenty of money to be made within the group.

- I’m reminded of the tautology that active managers underperform the indices (and therefore passive funds) – as a group.

What else would you expect?

- It’s always important to distinguish between useful average and heuristics, and ones that you can safely ignore.

Which brings me to my second point:

- Widely diversified stock portfolios will continue to do well, and will outperform other asset classes.

Index funds will continue to track their indices.

- For one thing, they don’t allocate an equal amount of money to stocks of different sizes (market caps).

Bessembinder hasn’t undermined the equity investment thesis.

- He’s exposed a previously unidentified concentration of returns.

- Which you can safely ignore in your investment process – if you want to.

So I draw a very different conclusion from Bessembinder’s work than does James Anderson.

- But then I don’t have an active fund to sell you.

Until next time.

The May 2018 version of the Bessembinder Report,

see for example:

http://www.q-group.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/10/Bessembinder_StocksTreasuryBills_paper.pdf

concludes its abstract with the following sentence “The results help to explain why poorly diversified active strategies most often underperform market averages.”

So it would seem that the author of the work may also not entirely agree with the conclusions of JA et al.

Also, that version of the paper contains a footnote to the Introduction that says “Since first circulating this paper, I have become aware of blog posts that show findings with a similar, though less comprehensive, flavor.”